Wandering the realms of effective altruism and similar lands where the rationalists, intellectuals, and otherwise cool kids roam may lead one to presume that utilitarianism is, well, Slave Morality for Nerds. At least, this is the impression of Brett Anderson who wrote a long post appealing to the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche and general prejudices regarding utilitarians, to say that:

What utilitarianism actually provides is a rational justification of the moral intuitions of a particular kind of person: most typically, utilitarianism will be appealing to nerdy (i.e., relatively autistic), WEIRD individuals.

It is specifically the consequentialism and systematization of utilitarianism he points to here, to form a kind of syllogism:

Consequentialist, systematizing moral thinkers are nerdy.

Autistic people are nerdy.

Friedrich Nietzsche.

Therefore: Utilitarians are autistic.

Possibly I’m doing Brett an injustice here. Granted, there may be some more reasonable way his argument could be framed. But ultimately philosophical arguments like this end up being no more than hypotheses to test. Right here I’m going to say the claim that “the utilitarian is likely to be a little bit of a nerd (i.e., a little bit autistic, and maybe more than a little bit)” is scientifically testable. In other words, if there’s some kind of relationship between utilitarianism and autism, this should be something we can detect through empirical means.

Well, it turns out that the psychological antecedents of utilitarianism have been studied extensively already. No need to speculate; we already have several reports about what utilitarians are like.

And given the way utilitarianism does seem to be a big deal for the cool kids who hang around online calling themselves rationalists—enough that they’re always asking each other things like Why is utilitarianism/consequentialism so common among rationalists, maybe we can learn something about the rationalist community if we can understand utilitarians better.

So… What Are Utilitarians Like?

Right away we have two published studies in which autism showed a negative relationship with utilitarianism.12 And while I tend to be wary about using only a couple of studies to confirm a suspicion, A) I can’t find other studies reporting anything else, and B) this is worse than just a couple of null results that might just represent a type II error. These findings are literally the opposite to the expectation: autistic people are less utilitarian than controls.

So I’m just going to say no, I don’t believe there’s any meaningful positive relationship between autism and utilitarianism.

Instead, we have numerous studies suggesting that utilitarians are less emotional, and less honest. Utilitarians are consistently found to be higher in the dark tetrad than conventional, non-utilitarian deontologists—in other words, utilitarians veer closer towards psychopathy, Machiavellianism, Narcissism, and sadism than the general population. Yes, that’s right: a large body of research finds that people who make moral judgments as utilitarians do are less good by most conventional metrics than other people.3456

So not only does utilitarianism seem to have nothing to do with autism, it definitely doesn’t seem to have any particular appeal to hypermoral, autistic people. Instead, utilitarianism looks like the moral system for people with weak moral drives.

But can this be right? Does it even make sense for there to be a moral system that appeals to people who are less moral than most people?

What are the studies really doing?

Looking closer that the studies themselves, the authors tended to define utilitarianism in terms of how people actually made moral judgments, rather than in terms of specific attitudes they agreed with. In other words, the utilitarians in their studies often weren’t people who said “Yes, I am a utilitarian,” but rather, they were people who showed little concern for principles like lying is bad, or killing is immoral, and instead indicated that they would take actions specifically to reach desirable outcomes.

These desirable outcomes weren’t purely selfish. Commonly, subjects in these studies reviewed scenarios allowing them the option to kill one person in order to save five lives; the utilitarian response sacrifices one life for the sake of five. But not all of these dilemmas are the same. It turns out that some dilemmas require the respondent to literally and directly murder someone to save others—say, by pushing one person in the way of a trolley—while others require the respondent to indirectly murder someone—say, by switching a trolley from one track with five people on it, to a track with one person on it.

(If you’ve seen that philosophical Netflix comedy The Good Place, you know what I’m talking about, here. If not, well, you can… trying seeing The Good Place? Welcome to the wide world of the Internet)

To a proper utilitarian, killing someone directly is, at least in theory, the same as killing someone indirectly. The outcome is what matters. Yet being forced to murder someone in order to achieve a desirable end will make most people balk. They might be utilitarian in theory, but then when it comes down to it, they just don’t feel like they can’t bring themselves to commit murder for the sake of saving lives.

There’s a book I like by Joshua Greene, called Moral Tribes. There, he discusses a research research programme designed to compare these two types of moral dilemmas, where people decide to indirectly sacrifice one person for the sake of many, versus directly murdering one person for the sake of many. It turns out that most ordinary people will flip a switch to save five people and kill one person, but that it’s mostly only the subjects with particular kinds of brain damage involving the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), a type of damage that causes emotional blunting—it’s mostly just people with damage to the VMPFC who will directly murder someone to save lives. Greene talks about one study comparing healthy controls with alzheimers patients, and subjects with frontotempral dementia (FTD), who are known for emotional blunting and lack of empathy. When the three groups were given these trolley problems, they answered differently:

In response to the switch dilemma, all three groups showed the same pattern, with at least 80 percent of respondents approving of turning the trolley to save five lives. About 20 percent of the Alzheimer's patients approved of pushing the man off the footbridge, and the healthy control group did about the same. But nearly 60 percent of the FTD patients approved of pushing the man off the footbridge, a threefold difference.7

The takeaway here is that some dilemmas don’t seem particularly hard. If you ask people, “Would you push a button to change it so that one person would die instead of five?” most answers you get sound pretty utilitarian. It’s specifically the footbridge-style questions that really get at who is a hard-care utilitarian and who isn’t. And it seems that to answer like a utilitarian consistently, you have to be willing to literally kill someone to save five other people. Ultimately, making a decision like this requires a person to do one of two things:

Think carefully, weigh consequences of actions, sweat a little, and then override an emotional inhibition, or,

Shrug, feel nothing, fail to see any dilemma, and conclude that it’s pretty obviously better to get an outcome where fewer people die.

There’s at least a possibility that the self-described utilitarian rationalists are mostly the first kind of person. In fact, there are studies that find utilitarians are more reflective,8 and have better working memory capacity than others—they can hold more information in mind at once.9 So the first kind of utilitarian does seem to legitimately exist. But invariably, when you carry out a study, you’re going to get a bunch of the second sort mixed in as well.

Do we have to call the second type of person a utilitarian? Is it fair to paint all utilitarians with a broad brush? Maybe the true utilitarians are only those people with good moral reactions, who suppress them thoughtfully, effortfully, even valiantly, to bring about a better world for us all?

A research team led by Guy Kahane published a 2015 article which took something very like this view.10 Like Peter Singer, the authors argue that proper utilitarianism is difficult and demanding, requiring that we sacrifice most or even all of our own wealth for the good of starving people elsewhere. Yet the type-two utilitarians identified across the research aren’t doing this at all; people who say they’d murder people in footbridge experiments also say they care about humanity as a whole less than others, and would donate less money to charity than other would. So the study authors conclude:

there is very little relation between sacrificial judgments in the hypothetical dilemmas that dominate current research, and a genuine utilitarian approach to ethics. 11

I don’t deny that there’s at least some kind of argument to be made here. But to me, it really feels like a no true Scotsman dodge. As an agnostic, I sometimes have to sigh and accept that there’s a lot of wishy-washy, anxious agnostics out there who lack self confidence and just get confused about religion; so agnostics on the average, agnostics taken as a whole are just more anxious, wishy-washy, and confused than I’d prefer to admit. But I don’t somehow get to kick them out of the group; there are no membership fees to be an agnostic. The reality is that other people may be agnostic for different reasons from those that are compelling to me. The same is true for utilitarians. Unless they’re going to institute some kind of credentialing system or set of secret handshakes, the term utilitarian will be broad enough to include the hand-wringing Peter Singer types along with amoral footbridge-lurkers waiting for trolleys to pass by.

But even more than this, it doesn’t seem to me that a utilitarian must only be type 1 or type 2. What about people who blend the types together? My sense is that most utilitarians become utilitarian because they’re both interested in outcomes, and feel less morally bound by restrictions than other people do.

Is this really right? Well, maybe rather than asking people to answer footbridge dilemmas or how much money they donate, we should just ask them “Are you a utilitarian?” and then see what kind of person says yes.

So What are Self-Described Utilitarians Like, Then?

Fortunately, I know some people who post at The Motte, a rationalist-leaning Reddit forum heavily saturated with fans of Scott Alexander’s old blog. And from them, I was able to obtain access to the data from a political survey of 535 respondents. I’ll have more to say about this survey another time; for right now what I want to talk about is a question there that asked people how much they agreed with the statement:

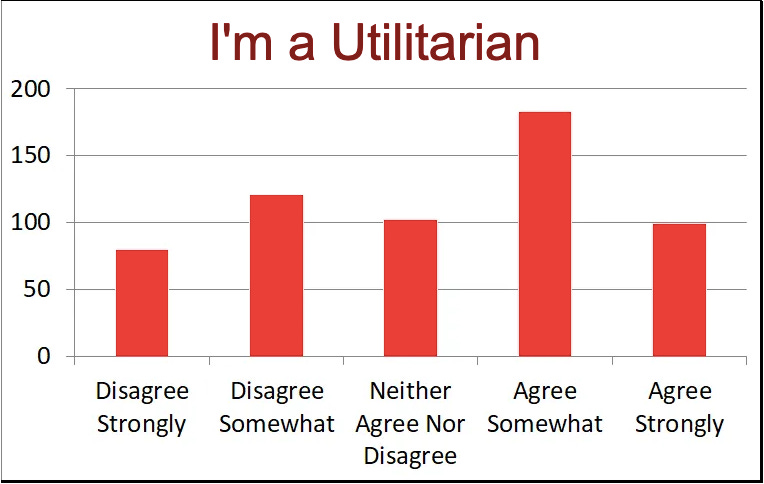

“I’m a utilitarian. (In other words, I believe the morally right action is the one that maximizes everyone’s overall happiness).”

In a representative sample of the United States, or all English Speakers, or all adults living on Earth, or whatever you think is the space we should be discussing here, you probably wouldn’t get that many people who agreed with that statement. But at r/TheMotte, it looks like there were quite a few utilitarians:

For comparison, here’s the distribution for religiosity in the same survey:

So it isn’t just that these people like agreeing with survey questions—the cool kids are pretty utilitarian.

Even more interesting, however, is the pattern of responses on the survey. When people say they are utilitarian, does this relate to the way they answer other questions?

Well first of all, the more important religion was to people in the survey, the less likely they were to be utilitarian (r = -0.24, p < 0.0000001). This is about what we should expect to see, given that cross-nationally, atheists lean towards consequentialist moral systems.12

But I’ve commented in the past that atheism and utilitarianism go together like peanut butter and iron filings, so this doesn’t seem to be a straightforwardly rational preference to me. Checking the factor structure of this survey reveals that respondents were more strongly utilitarianism the more pragmatic and left-leaning they were. (Put another way, any given respondent tended to be more utilitarian as they became less idealistic and less conservative). Other attitudes identified in the survey as pragmatic and left were things like “prostitution should be legal,” “Psychedelics should be legal,” and “People suffering from incurable diseases should have the right to be put painlessly to death;” utilitarians tended to agree with all of these statements.13

Looking at all this, maybe we might think utilitarians were just leaning libertarian, right? But utilitarianism turned out to be (nonsignificantly) less common among self-described libertarians.14 So instead, it looks like utilitarianism just appeals to the same kinds of skeptics, materialists, and hedonists who go in for moral relativism and progress—even if that progress compromises intangible values like love or the sacredness of human life. This is rather what atheists are like in general: atheists are better at reasoning, but less altruistic, fair, and forgiving in temperament,15 and it appears that they donate less to charity and volunteer less of their time for others.16

So you may take something else away from this than the conclusion I draw. But when I look at all this, it really does seem to me as though utilitarians definitely include not only the first type of rational, careful, motivated thinkers, but also the second type of utilitarian, the kind of person you wouldn’t consider to be very moral at all.

Conclusion

Now before you get mad (OK well maybe now that you’re already mad, sorry) this isn’t intended to be completely critical of utilitarians. Let’s stop a moment and compare them to the woke, another group of people on the political left who don’t seem like utilitarians at all. The woke give me the impression of being unreflectively idealistic and deeply morally motivated—indeed, conversation with the woke is so morally charged that in my experience they won’t even talk to me respectfully; they just lecture me and expect me to agree, because otherwise I’m an evil person. To their credit, utilitarians aren’t generally like this. They will actually talk to me even after finding out I’m not a utilitarian, and, hey, I like that.

You may also find, if you’ve hung around with a lot of utilitarians long enough, that utilitarians really don’t feel like sleazy “get what you can” telemarketers and politicians who would steal candy from a baby and then plead for mercy because their blood sugar was low, and also they never got any candy when they were babies. A lot of utilitarians have sort of defaulted to utilitarianism because, even though they’re pretty skeptical about things, they really do like morality, or at least the idea of morality, and utilitarianism is all they can really tolerate. While they may indeed be less morally motivated than most people, for many of them, utilitarianism seems like a place they’ve retreated to out of frustration for the lack of any better way of organizing their feelings about morality. As eight unread emails writes on r/slatestarcodex,

Actual 100% utilitarians who embrace all repugnant conclusions are few and far between.

So why are rationalists so sympathetic to utilitarianism? I think the obvious answer is that the alternatives to utilitarianism aren’t very good.

If you don’t believe in God, but still feel as though morality matters somehow, you can’t justify morality with religion. What do you do? Well unfortunately, rather than just admitting morality may not exist, it seems you rationalize it into existence, because you’re a rationalist, and that’s what rationalists do.

To me, this is the real argument against utilitarianism. It isn’t that utilitarians are autistic, or that they lack moral feelings, but rather that there is no way to substantiate utilitarianism logically or empirically. Even I don’t know many truly amoral utilitarians, but I do bump into a lot of self-described rationalists who want to be “Less Wrong,” and then whatever, just believe whatever they want and cobble together the explanation afterwards. If you call yourself a rationalist, and then find you are concerned with moral systems matching your intuitions, just remember, this is the same reason George W. Bush felt sustained by the prayers of his supporters: “I just feel it.”

And with this in mind, maybe all the traction utilitarianism has gained amidst the cool kids is just something that’s happened lately, because of sites like Less Wrong. Right? For a while there the nerds cool kids all used to be Christians, founding schools like St. Patrick, Brigid, and Columbia did,17 or writing philosophical tracts like St. Paul or St. Augustine did. For a while it really seemed like the intellectuals were in change of that Old Time Religion.18 But however much they may have once liked Christianity, they didn’t stay there—ultimately they left Christianity when it became uncool, so hey, maybe they’ll leave utilitarianism as well, once they realize it’s just a fad.

For what it’s worth, I hope it’s just a fad. The rationalists aren’t going away, and while a lot of the things they dream up are really fascinating, utilitarianism was never one of those things. Take my advice, people: If you don’t like conventional moral systems, there’s always moral nihilism.

Patil, I., Melsbach, J., Hennig-Fast, K., & Silani, G. (2016). Divergent roles of autistic and alexithymic traits in utilitarian moral judgments in adults with autism. Scientific reports, 6(1), 23637.

Clarkson, E., Jasper, J. D., Rose, J. P., Gaeth, G. J., & Levin, I. P. (2023). Increased levels of autistic traits are associated with atypical moral judgments. Acta Psychologica, 235, 103895.

Djeriouat, H., & Trémolière, B. (2014). The Dark Triad of personality and utilitarian moral judgment: The mediating role of Honesty/Humility and Harm/Care. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 11-16.

Dinić, B. M., Milosavljević, M., & Mandarić, J. (2021). Effects of Dark Tetrad traits on utilitarian moral judgement: The role of personal involvement and familiarity with the victim. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 24(1), 48-58.

Dabbs, A. C. (2020). Clarifying the Role of Personality in Sacrificial Moral Dilemmas: The Big 5 and HEXACO Predict Deontological and Utilitarian Tendencies.

Kroneisen, M., & Heck, D. W. (2020). Interindividual differences in the sensitivity for consequences, moral norms, and preferences for inaction: Relating basic personality traits to the CNI model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(7), 1013-1026.

Greene, J. (2014). Moral tribes: Emotion, reason, and the gap between us and them. Penguin.

Paxton, J. M., Ungar, L., & Greene, J. D. (2011). Reflection and reasoning in moral

judgment. Cognitive Science, 35, 1–15

Moore, A. B., Clark, B. A., & Kane, M. J. (2008). Who shalt not kill? Individual

differences in working memory capacity, executive control, and moral

judgment. Psychological Science, 19, 549–557.

Kahane, G., Everett, J. A., Earp, B. D., Farias, M., & Savulescu, J. (2015). ‘Utilitarian’judgments in sacrificial moral dilemmas do not reflect impartial concern for the greater good. Cognition, 134, 193-209.

Ibid.

Ståhl, T. (2021). The amoral atheist? A cross-national examination of cultural, motivational, and cognitive antecedents of disbelief, and their implications for morality. Plos one, 16(2), e0246593.

For the statistically minded, r = 0.17, 0.10, and .20 respectively, with all p-values below 0.03.

Here two-tailed p = .11, for those of you who, y’know, just really love p.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2021). A review of personality/religiousness associations. Current Opinion in Psychology, 40, 51-55.

How Religion Affects Everyday Life. (2016, April 12). Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 4, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2016/04/12/religion-in-everyday-life/

“Education - Charlemagne, King Alfred, and Monastic Reformers.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/education/The-Carolingian-renaissance-and-its-aftermath. Accessed 16 June 2023.

Admittedly, I don’t have much in the way of psychometric evidence from the Middle Ages; still, it’s hard to argue that all the hardcore pagans who insisted that literacy was for the weak were attracting a large contingent of medieval cool kids.

"To me, this is the real argument against utilitarianism. It isn’t that utilitarians are autistic, or that they lack moral feelings, but rather that there is no way to substantiate utilitarianism logically or empirically. Even I don’t know many truly amoral utilitarians, but I do bump into a lot of self-rationalists who want to be “Less Wrong,” and then whatever, just believe whatever they want and cobble together the explanation afterwards. If you call yourself a rationalist, and then find yourself you are concerned with moral systems matching your intuitions, just remember, this is the same reason George W. Bush felt sustained by the prayers of his supporters: “I just feel it.” "

What you have noted here, and by noting it you have noticed more… is I what call this the world-building urge. Everyone empathic world-builds except narcissists and psychopaths, who are the world and are perfect as they are. (this is the notice that should reframe after the notice you have written above)(neo-Pyrrhonism is not far away) Worldbuilding urge does not care what the outcome is, much the same way hunger does not care what you eat, and definitely not recipe you use to make a meal you share with others, even with the 'W'.

Perhaps the reason utilitarianism is to many more appealing than moral nihilism as you describe it is that utilitarianism is universally applicable; in theory, I can behave in a way that is consistent with utilitarianism and I can ask that other people also behave in that way. My moral intuition, by comparison, may be completely different from that of my neighbor, or someone living on another continent. Encouraging other people to follow their moral intuitions (or other intuitions) has the potential to directly contradict mine. Because moral nihilists rely more overtly on intuition, moral nihilism can answer the question, ‘what should I do?’ but cannot answer the question, ‘what should we do?’ In this way, utilitarianism (though flawed) offers a sort of social contract that moral nihilism cannot.