Humanity’s relationship with alcohol is ancient and deep. Analysis of jugs from the late stone age shows we have been producing alcohol since the early Neolithic, around 10,000 years ago.1 But because The Past Was More Than You Think, there may very well have been thousands of years of alcohol production before that. Indeed, it appears our ancestors may have been consuming significant quantities of alcohol in fermenting fruit for the last 40 million years, ten times longer than our split from chimpanzees 4 million years ago.2

Of course, how much alcohol our hairy grandparents were actually consuming is open to question; and even presuming alcohol formed a significant portion of their diet, evolution doesn’t always respond to selection pressures immediately. It seems there’s always a mismatch between a species and its environment, and quite possibly as long as 30 million years passed before our ancestors were any good at processing the alcohol they’d been consuming. But a 2014 study did find positive evidence for enzymes that digest alcohol having appeared in our biology 10 million years ago:

We resurrected ancestral ADH4 enzymes from various points in the ∼70 million y of primate evolution and identified a single mutation occurring ∼10 million y ago that endowed our ancestors with a markedly enhanced ability to metabolize ethanol. This change occurred approximately when our ancestors adopted a terrestrial lifestyle and may have been advantageous to primates living where highly fermented fruit is more likely.3

No surprise then that almost every culture with access to containers has used them to produce some form of alcoholic beverage, cherished for its inebriating qualities, enjoyed socially, or consumed in sacred rituals.4 Drinking also has widespread use in ceremonies consolidating tribal loyalty.5 And the medicinal use of alcohol has a long history as well, dating back at least to 2000 BC, when Sumerian recipes for herbal remedies dissolved in beer were preserved on cuneiform tablets.

It is this medical aspect of the topic that I want to explore today, by asking the question: Is alcohol good for us?

Is Alcohol Good For Us?

Despite our long association with alcohol, there have also been many who swore it off entirely. Mormons and Muslims classically abstain for religious reasons, and there have been a few secular teetotalers as well. For example, Howard Phillips Lovecraft wrote extensively about his refusal to drink:

I have never tasted intoxicating liquor, & never intend to; having a strong aesthetic disgust at anything which blunts or coarsens the delicate natural equipoise of the evolved human intellect & imagination… The existence of intoxicating drink is certainly an almost unrelieved evil from the point of view of an orderly & delicately cultivated civilization; for I can't see that it does much save coarsen, animalise, & degrade… Let the graces of wine live in literature—its function in the life of a delicate & fastidious civilisation would seem to me definitely outmoded. In my own family, wine has been banished for three generations; & only about a quarter of the conservative homes of this section retain any regular use of it.6

But, well, it must be admitted that Lovecraft was as mad eccentric as any of our favorite authors, and if he didn’t die of suicide (like Robert Howard did) he ultimately succumbed to cancer of the small intestine at 46. Granted, Lovecraft didn’t eat that well. But perhaps part of the problem was that he didn’t drink well, either.

I’m being deliberate in my phrasing here, because if we look at meta-analyses on alcohol consumption, what we see overall is actually rather surprising. We hear that moderate drinking is probably OK, while heavy drinking is clearly bad for us. But this isn’t what the research actually seems to suggest.

Not Too Little, and Not Too Much?

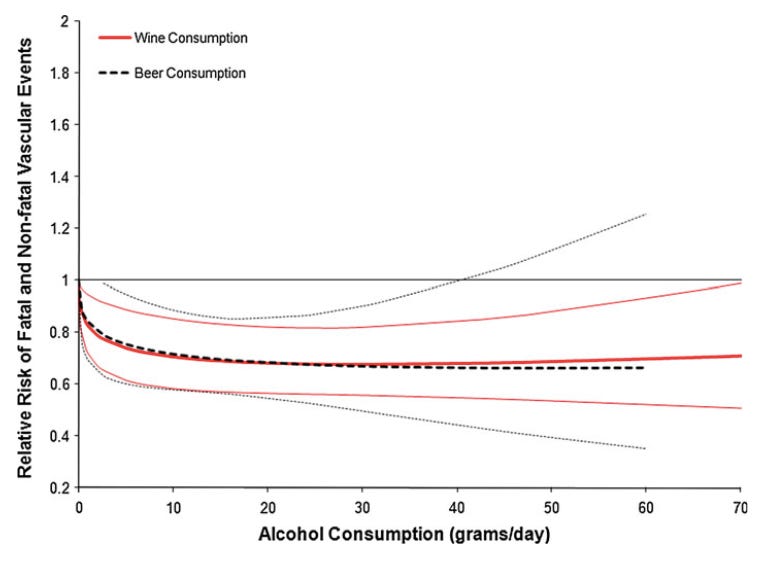

The first meta-analysis I want to look at is from 2011, where the authors compared cardiovascular events (read: heart attack) in relation to people’s consumption of beer, wine, and spirits. Probably because they only included studies written in English, geographically the studies were limited to the USA, Australia, and a broad range of wealthy European countries such as France, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and the Czech Republic. The authors begin by noting that “The relationship between alcohol consumption and cardiovascular events or all-cause mortality in apparently healthy people or cardiovascular patients has been depicted as a J-shaped curve attributed to a dose-related combination of beneficial and harmful effects.” In other words, that heart problems first drop, and then rise as rates of drinking increase.7

But their findings don’t actually show results that look like the letter “J” as much as curves that slope downward, and gradually flatten out:

If we only look at the upper edges of these curves—at the dotted lines that show the edge of statistical significance—we do see beer consumption (in black) stops giving any significant protection against heart attack at around 40 grams/day. That’s approximately three drinks a day by American standards. But for wine (shown in red) the protective effects are significant out to 70 grams/day, which is five drinks a day.

Coming from someone whose alcohol consumption over the last few days was a single glass of watered rosé (you know, the way the ancient Athenians drank it; I’m not a barbarian), the idea of having five glasses a day on average is surreal. I don’t know about you, but for most of my life I doubt I’ve had the time, desire, or money for more than 1800 glasses of wine a year.

And if we turn back to the graph above and check the center of the effect lines—the most likely effects of drinking on heart attack—there is no point at which alcohol consumption ceases to be protective. If we believe these results, even raging alcoholics are evidently doing themselves a favor staving off heart problems.

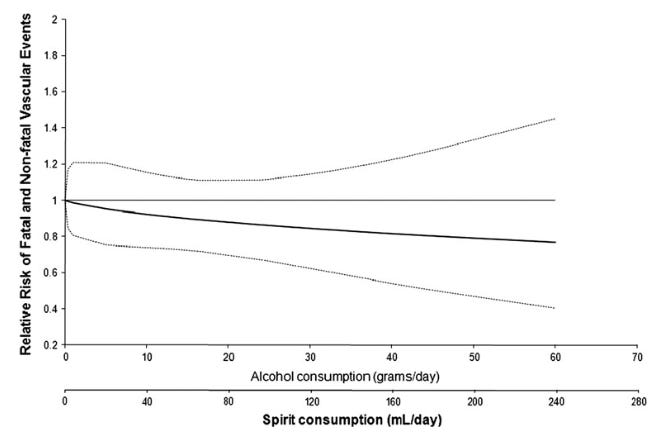

So much for beer and wine, but what about those who drink spirits? Here are the results from the same 2011 meta-analysis on spirits:

The same thing seems to be true for hard liquor—there’s not much “J” to this curve. Although the overall effects are nonsignificant either way, it doesn’t seem there’s any evidence that people who drink quite a bit of brandy or vodka are at greater risk for cardiovascular disease.

And all this seems striking to me. Moderate drinking is usually described as 1-2 glasses a day. Headlines like “How to Figure Out if Moderate Drinking Is Too Risky for You” from Scientific American describe moderate drinking as only 1 drink a day. But this analysis says that in order to actually see any statistically significant health problems from alcohol, you seriously have to drink like a fish:

This chart is different from the others—it’s all-cause mortality for wine, rather than cardiovascular problems. (They don’t show a similar chart for beer.) But look, in order to see a significant elevation in all cause mortality, you need to be drinking an average of over 100g of alcohol per day. That’s 7 or more drinks a day, on average. So some days, maybe only two or three drinks, and other days, you know… twelve.

The study authors do remark that binge drinkers are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease, and cite a few studies for the claim. When I check their citations, it doesn’t appear that all of the cited studies do support that, but at least one does mention that heavy drinking, and drinking outside meals, relates to increased risk of cardiovascular disease independently of the quantity consumed.8

So maybe it’s sensible not to go on a bender, or to drink heavily outside of mealtimes. But if that’s true, how large could the effect be, if we can’t see clear evidence for cardiovascular disease even up to 70g of alcohol a day? Why no evidence for elevated mortality until we reach 100g a day? Binge drinking is defined by the CDC as 5 or more drinks in a two-hour period for a man, or 4 or more drinks for a woman. 70g is already 5 drinks by American standards, and if you believe these results, there’s no evidence for any problems in people who average 5 drinks a day, every day.

Are the results believable? Long term readers will know I’m a hard-core empiricist. I think it’s usually most honest to just take research findings directly, at face value, particularly when they come from a meta-analysis that combines the results of numerous studies. If the research says alcohol is protective of cardiovascular health, even as we veer towards levels of drinking that make me personally uncomfortable, that’s just what the research says.

Granted, that doesn’t mean there was no possibility for fraud in this case. Maybe being sponsored by Cervisia Consulenze and Istituto Nazionale per la Comunicazion encouraged the scientists carrying out this meta-analysis to lean on the scales for some reason, though I can’t see why that would be the case. More plausibly, the integrity of the researchers carrying out the individual studies was compromised; there have been reports of alcohol suppliers spending $100 million on research around 2017, though admittedly that was after the meta-analysis was completed9, and while a more thorough investigation of studies carried out from 1967 to 2019 did find evidence for occasional (if substantial) industry funding, they didn’t see any straightforward relationship between co-authorship network formation and alcohol industry funding of epidemiological studies on alcohol and cardiovascular disease, which was the subject of this study I’ve been discussing here.10

If you really wanted to make a case for these results being compromised by fraud, you probably could. But given the general discomfort surrounding alcohol consumption—discomfort which comes in no small part from the teratogenic effects of alcohol on a developing fetus, as well as the dangers of driving under the influence of alcohol—isn’t is also likely that our culture would have a bias against recognizing the health benefits of drinking? There’s always a desire to smooth over complexity; it’s much easier to pass legislation against drinking, and push a straightforward message to the public about how “alcohol is dangerous and unhealthy and also bad,” than it is to say “alcohol may have both benefits and risks.”

So I’m not convinced that fraud is the only thing that could be compromising our trust in these results. Maybe funding by alcohol companies might encourage researchers to toss studies showing alcohol is unhealthy into the file drawer rather than publishing them. Maybe funding by alcohol companies might literally be encouraging scientists to fabricate data out of thin air, and publish studies that were never carried out at all. But anti-alcohol bias seems also quite plausible as a reason to toss out the opposite studies showing alcohol is healthy, or to misinterpret or p-hack results to support an anti-drinking narrative. And both of these problems remain to actually be substantiated; both fraud and bias are hypothetical problems that haven’t been shown to compromise the research here.

The only thing I can take away from this 2011 meta-analysis, then, is when it comes to heart health, the best advice is “Not too little, and don’t drink like a fish.”

Spock’s 2020 Advice on Drinking

The previous study focused on heart health. But arguably, the results for all-cause mortality are more important. After all, even if your heart beats like a metronome, that won’t help you much as you’re dying of liver cirrhosis. And if we’re feeling as though it’s a bit late in the 21st century to be poring over meta analyses from 2011, and maybe it’s better to have some more modern information, then here’s a large scale 2020 study from the Netherlands11 that can give you good advice on how to live long and prosper.

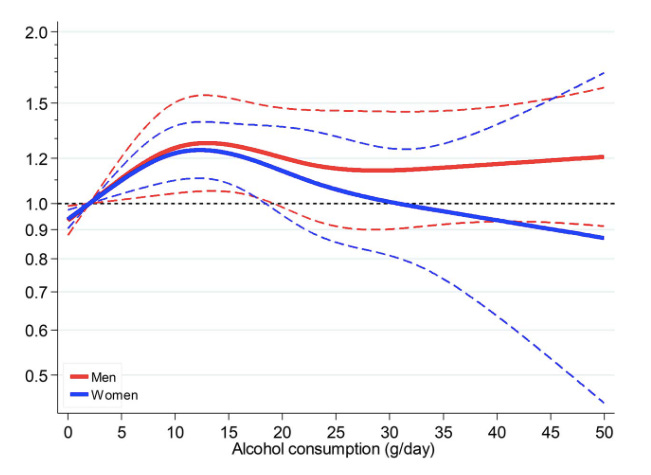

The upside to this second article is that it took its data from the Netherlands Cohort Study, which was quite large—it included 7807 participants born in 1916–1917. The downside to the study is that, just as you were getting used to graphs of cardiovascular events, where up is bad, they are now talking about the relative chance of surviving to age 90, and up is good. This means flipping all the graphs vertically, so we’re going to be looking for upside-down J curves, or eta curves. (That’s η-shaped curves for those of you who are a little rusty on your Greek)

So right away we see a result very similar to those from the meta-analysis on cardiovascular health. Moderate drinking is significantly better than abstention, just as before. Outcomes are significantly improved for those drinking between 3 and 18g of alcohol per day, which is somewhat tighter, and matches better what most of us think of as “moderate drinking.”

But there’s no evidence for any problems with drinking too much alcohol. Going all the way up to 50g/day, there’s no statistically significant evidence for early deaths attributable to overindulgence. The average odds for men reaching age 90 even continue to remain around 1.2 at 50g/day, without any sign of turning around at all.

This data could be implying drinking at somewhat lower levels is ideal because longevity includes important factors beyond just cardiovascular health. That would probably be the straightforward interpretation. But as the authors point out, this was an elderly sample, whose livers and kidneys could have been stressed by medications. There's also a third possibility: The study authors mentioned controlling for education. This is pretty good overall, though introducing controls always weakens signals in the data, which would broaden the 95% confidence intervals vertically, thus shrinking the horizontal range of significant effects.

I lean towards the straightforward interpretation: We have evidence that in later life, drinking between 3g and 18g of alcohol per day—about 1 drink daily or less—is associated with increased survival to age 90. This is in comparison to people who abstain from alcohol entirely or who drink more than this.

But what we don’t have is any clear evidence that drinking over 50g per day is associated with reduced survival to age 90. Is there a significant impact of genuine overdrinking on longevity? And assuming there is, how much alcohol per day might that mean?

Searching For the Downsides to Overdrinking

Attempting to find a check on this, I dug through another Dutch meta-analysis from 202112 on general lifestyle factors related to longevity. This article wasn’t focused on drinking; it was looking at a broad range of factors to determine which of them were associated with mortality.

The usual predictors made an appearance: type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, LDL cholesterol, and smoking were associated with shorter lifespans, while HDL cholesterol and education gave higher odds of long life. But while alcohol dependence (i.e. being an alcoholic) was related to earlier death, overall alcohol consumption was not. The authors write that “This might suggest that especially excessive drinking affects longevity,” which does at least seem reasonable. It doesn’t tell us where a person crosses from just drinking into overdrinking, though.13

It turns out that if you really want to be thorough about things, you need to go to the Japanese—specifically, to a 2010 review of six studies containing over 309,082 individuals.14 This one looked very promising from the outset. So what were the findings?

The Japanese study replicated the finding of an ideal level of drinking. Specifically, it found reduced mortality for moderate drinkers—meaning those who drink under 46g/day for men, or under 23g/day for women—compared to controls who never drank at all. But this isn’t “moderate drinking” by most standards. And looking at those people who are drinking over 69g/day, and even over 92g/day, didn’t reveal they had straightforwardly higher mortality. Yes, when early deaths, ex-drinkers, or non-smokers were excluded, the category of the very highest drinkers had significantly elevated morality—but how meaningful is an effect that you have to shop around to substantiate in a sample of over 300,000 people?15

It wasn’t until I turned to Latin America that I found any clear evidence for downsides to heavy drinking. Although the 2023 study I found also had a reasonably large sample size with 44,394 participants, it didn’t report drinking in terms of grams/day, but rather frequency of drinking, ranging from never to daily. The study wasn’t looking at longevity, but at healthy aging, in terms of cognitive processes and subjects’ ability to carry out daily tasks for themselves. And while the effect size on drinking was small, it was at a least statistically significant: heavier drinking was related to modest impairments in both cognition and functioning.16

In other words, while you might have to drink extremely heavily to limit your ability to live long, if you’re drinking every day, you’re probably already finding it harder to prosper. (If you’re a Vulcan who lives in Latin America, anyway)

Conclusion

Our species has a long and complex relationship with alcohol. Originally consuming it opportunistically in overripe fruit lying on the ground, we gradually shifted to producing alcohol on our own, in vessels of our own design. Over deep evolutionary time, the Hand of Nature worked its Will upon us; what began as a tentative flirtation with intoxicants made its way into social norms and religious rituals. Gods inspired its production;17 Gods demanded its consumption.18 What was once an unambiguous toxin became more tolerable, a thing to which we were gradually accustomed, and finally, a nutrient our bodies have come to rely upon.

It bears remembering that these are the writings of a man you met over the Internet, not a licensed medical doctor, let alone your personal physician. But if you’re interested in living a long and healthy life, my personal reading of the literature suggests that you should have a few glasses with your supper now and then, unless:

You’re underage and it’s illegal

You’re pregnant and it’s irresponsible

You’re about to drive and it’s crazy

You’re taking medication and it strains your kidneys or liver

You’re an alcoholic and it’s seriously a bad idea

You’re H.P. Lovecraft (or similar historical figure) and it’s too late now

Your ancestry affords poor ability to metabolize it and it messes you up, or,

You’re Anders and just can’t be persuaded to listen to reason on this one

Wait! Apple Pie, You Forgot to Mention Honesty-Humility in This Post!

Oh, sorry—People with alcohol use disorder are significantly lower in Honesty-Humility (and Conscientiousness) than normal controls.19 Just as smoking and obesity are general risk factors for health problems, poor moral fiber is a general risk factor for behavioral problems.

Charles H, Patrick; Durham, NC (1952). Alcohol, Culture, and Society. Duke University Press (reprint edition by AMS Press, New York, 1970). pp. 26–27.

Dudley, R. (2002). Fermenting fruit and the historical ecology of ethanol ingestion: is alcoholism in modern humans an evolutionary hangover? Addiction, 97(4), 381-388.

Carrigan, M. A., Uryasev, O., Frye, C. B., Eckman, B. L., Myers, C. R., Hurley, T. D., & Benner, S. A. (2015). Hominids adapted to metabolize ethanol long before human-directed fermentation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(2), 458-463.

Hockings, K., & Dunbar, R. (2019). Alcohol and humans. Alcohol and Humans: A Long and Social Affair, 196.

Loeb, E. M. (1943). Primitive intoxicants. Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 4(3), 387-398.

Lovecraft, H. P. (1968) [written February 13, 1928] “To Zealia Brown Reed.” In Derleth, August; Wandrei, Donald (eds.). Selected Letters. Vol. II. Sauk City, Wisconsin: Arkham House. pp. 229-231.

Costanzo, S., Di Castelnuovo, A., Donati, M. B., Iacoviello, L., & de Gaetano, G. (2011). Wine, beer or spirit drinking in relation to fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. European journal of epidemiology, 26(11), 833-850.

Rehm, J., Sempos, C. T., & Trevisan, M. (2003). Alcohol and cardiovascular disease--more than one paradox to consider. Average volume of alcohol consumption, patterns of drinking and risk of coronary heart disease--a review. Journal of cardiovascular risk, 10(1), 15-20.

McCambridge, J., & Mialon, M. (2018). Alcohol industry involvement in science: A systematic review of the perspectives of the alcohol research community. Drug and alcohol review, 37(5), 565-579.

McCambridge, J., & Golder, S. (2024). Alcohol, cardiovascular disease and industry funding: A co-authorship network analysis of epidemiological studies. Addictive Behaviors, 151, 107932.

Van den Brandt, P. A., & Brandts, L. (2020). Alcohol consumption in later life and reaching longevity: the Netherlands Cohort Study. Age and ageing, 49(3), 395-402.

Van Oort, S., Beulens, J. W., van Ballegooijen, A. J., Burgess, S., & Larsson, S. C. (2021). Cardiovascular risk factors and lifestyle behaviours in relation to longevity: a Mendelian randomization study. Journal of Internal Medicine, 289(2), 232-243.

Ibid.

Inoue, M., Nagata, C., Tsuji, I., Sugawara, Y., Wakai, K., Tamakoshi, A., ... & Research Group for the Development and Evaluation of Cancer Prevention Strategies in Japan. (2012). Impact of alcohol intake on total mortality and mortality from major causes in Japan: a pooled analysis of six large-scale cohort studies. J Epidemiol Community Health, 66(5), 448-456.

Ibid.

Santamaria-Garcia, H., Sainz-Ballesteros, A., Hernandez, H., Moguilner, S., Maito, M., Ochoa-Rosales, C., ... & Ibanez, A. (2023). Factors associated with healthy aging in Latin American populations. Nature Medicine, 29(9), 2248-2258.

Pater, W. H. (1876). A STUDY OF DIONYSUS. Fortnightly, 20(120), 752-772.

The Book of Mark, chapter 14, verses 23-24.

Rash, C. L. (2018, September). An Examination of the HEXACO Model of Personality in Alcohol Use Disorder, Cannabis Use Disorder, and Gambling Disorder. Arts.

Something that might explain why moderate drinking seems to correlate with less heart disease is that many women (myself included) find that during perimenopause, menopause and post-menopause we become quite alcohol-intolerant. Even a single drink will result in poor sleep, hot flashes, etc., so many of us decide it isn’t worth the discomfort at all. At the same time, the abrupt drop in estrogen during menopause makes us increasingly vulnerable to cardiovascular disease. I’m a nonsmoking, healthy weight athlete who has just been diagnosed with moderate atherosclerosis - and this is not at all uncommon in my age group. My conjecture is that those of us who are predisposed to heart disease (family history) are also the ones who find that alcohol induces unpleasant symptoms; and recent research shows that women who experience hot flashes are at a higher risk of heart disease. So it may be not so much that alcohol has a protective effect, but rather that the only people who can keep consuming alcohol through middle age and beyond are the ones without underlying genetic propensity for heart disease.

Hold your horses here. I am very reasonable. And your analysis misses an important section, namely a cost-benefit analysis. My non-consumption of ethanol based beverages is foremost a matter of great stinginess. Alcohol is expensive (especially so in high-tax socities) and, for me at least, simply not worth the cost.