There is only one really serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Deciding whether or not life is worth living is to answer the fundamental question in philosophy. All other questions follow from that.

—Albert Camus

Sarah Perry is one of the great undiscovered geniuses of the 21st century. Her writing, when she puts the proper time and seriousness into it, is an absolute joy to dive into for its rare combination of philosophical innovation and rigor.

Today I’m going to be discussing her best work, Every Cradle is a Grave—if you think she has written anything better, please do let me know about that in the comments. Some readers may be familiar with similar arguments by David Benatar, whom she also mentions, but Benatar’s work isn’t as convincing. Ever since I found Every Cradle is a Grave, I’ve been poking around the Internet looking for other essays by Sarah Perry, and they’re around. They’re imaginative and interesting, too, but they mostly come across as breezy explorations of some minor idea about how people should try jogging while stoned or people should use city streets for religious gatherings or whatever. She got lucky with her article about beauty, but more because it was a joy to read than because it was particularly noteworthy.

Every Cradle is a Grave is different. Sarah Perry doesn’t bother with any of this loose argumentation over loose change here. She has something genuinely different to say—Sarah Perry wants to convince you that suicide is a reasonable choice, that life on Earth is a tragedy, and that having children is morally wrong. She knows you won’t believe her. She knows she’ll come across to most people as a weird cartoon villain. So she has no choice but to be very, very careful.

The stance she takes in Every Cradle is a Grave makes her a kind of anti-Apple Pie.1 I haven’t posted much on this blog, but I’ve already written at length about how great life can be if you know how to live it. If you’re thinking about taking your own life—especially if you’re still young—then you have my sincere sympathy, but my advice is definitely to reconsider. Life may seem impossible to change in the short run, but in the long run, there are many things you can do to make it better.

Moreover, a critical ingredient in improving my own life has been to completely ignore Sarah Perry, build a strong marriage, and raise a house full of children. Although my wife and I made the decision to have a large family long before I came across Perry’s work, our last child was nonetheless born after I bought and read Every Cradle is a Grave. Little #6 is, in that sense, tangible evidence for my disagreement with Sarah Perry that creating new life is immoral.

When my kids get older, they’ll know all about her. Her book will be sitting on our shelves until I die, and her name will come up in conversation whenever anyone asks why anyone would act as though their life were a burden. (“Well, according to Sarah Perry, they’re acting that way because—wait for it, kids—they experience life as a burden.”) Maybe the most fitting end for a good cartoon villain is that she be remembered fondly for years and years by the people whose lives she tried so earnestly to prevent. Because if I disagree with her, it’s not because most of what she says is wrong. In fact, in this book at least, almost everything she says is brilliant.

Here is what I mean.

The Preface

People don’t often change their minds about ethics. When they do, it is generally for social reasons, not because they are exposed to reasoned argument. Reasoned arguments more often allow people to cement their existing opinions…

[T]o the extent that the reader holds contrary, pro-life, anti-suicide beliefs, I understand that exposure to my unorthodox views may only reinforce those beliefs.

Believe it or not, that seems pretty rational to me. To respond to crazy-sounding out-group beliefs with increased faith in the in-group beliefs validated by known and trusted authority—is a smart strategy. From the trenches of interpersonal communication, I don’t think ad hominem is even much of a fallacy. On the contrary, consciousness—and all knowledge—is social in nature; and most of our knowledge comes not from direct experience or through reasoning, but from trusted sources… [w]e get some of our ethical beliefs from direct intuitive perception, but we also rely on the ethical beliefs of those around us to shape our own beliefs and actions.

This patient way of accepting us for the flawed beings we are runs through the entire book. Sarah Perry has reached an interesting place for someone who loves death: she’s far from an idealist, but nor exactly is she a jaded cynic. Ultimately she comes across as a person both wise and sad, someone who knows that she’ll be rejected with horror whenever she speaks to anyone, seriously and directly, about the things that are closest to her heart. And yet, she remains sympathetic anyway:

[W]hether or not you allow me to influence you with my dangerous ideas, I hope you will believe me when I tell you that I am very much on your side. You are, after all, an aware being having experiences. This is true whether or not you have or will have children, and this is true whether you want to live or want to die.

Thank you for reading my book.

You’re welcome, Sarah. Thanks for writing it.

The Difficulty of Suicide

Ordinarily when I read people’s work, passages jump out as being odd, incorrect, badly reasoned, or flatly bizarre; it’s usually a simple matter to quote them and point out the problem. But Perry’s book is rich in empirical support, and she makes few claims. When she does make contentious statements, she’s very careful to say less than you can tell she wants to say, which is good practice. (Something I learned early on from arguing on the Internet: If you know you have the evidence for 90 percent, give support for 50, and demand 25. You’ll never get 100 percent; people don’t work that way online.)

So rather than quoting her at length, I’ll try to summarize what seems most important for her position. Her argument is, essentially, this:

Bloggers like Bryan Caplan say that life is obviously great, because otherwise people would be killing themselves like crazy. Caplan is a clever fellow, but this is still an utterly thoughtless position to take. Many people suffer through lives they do not have the courage or ability to end, because in reality, suicide is frightening, difficult, and risky.

Though Caplan may be unaware of it, numerous of barriers prevent even people in absolutely hopeless and miserable positions from taking their own lives. A large body of research establishes that people generally only commit suicide when they’re familiar with a specific method—one method will not substitute easily for another, because they must habituate themselves towards any given method before being comfortable, and competent, enough to attempt it.

Let me try to make this more realistic by giving a specific example.

The Story of B

I didn’t grow up in the land of winter snows, open space, and wild apples. Nope! Once upon a time, I lived in the big city, and life was pretty rough. Jobs were competitive, crime was frustrating (I had my car stolen three times), and cost of living was always high enough that we were never able to do more than tread water, financially. Large families are most definitely not economically sound in urban areas. So several years ago my wife and I decided to get out, and we’re very glad we did. But as we stacked our most sentimental packages in the garage in preparation for the move, I came across old letters and old drawings, and I realized something: There were a few people I’d lost touch with, people I’d grown up with, people I wanted to reconnect with, even if only to say goodbye. I’ll call these childhood friends B, C, and S.

When I looked B up, he didn’t have recent posts on social media, but I kept looking. I knew his old addresses and the schools we went to because I’d met him at school, and I’d been to his house many times, eating the vanilla bean ice cream his mother liked to buy. Eventually I found a funeral home claiming they had interred someone with his name and age.

Chilled by the discovery, I gave them a call, trying to confirm the situation and ask for details. We’d lost touch, so it was no surprise that I hadn’t been informed, but he should have been young and healthy, so couldn’t they explain how he had died? No, they couldn’t—not to someone who wasn’t a family member.

But S also grew up with B, and I was able to reach S. At first S was reluctant to say anything about it, but I already had a sense of the reality, and when I pressed him, he admitted the truth: B had killed himself with a firearm.

It’s easy to ask why; speaking superficially, B had a lot going for him. He was musically talented and attractive to women, but like millions of other people everywhere, he suffered from problems with self esteem, and suffered from a deep disconnection and ambivalence towards the world he lived in.

I do know that, in the years leading up to his suicide, B grew accustomed to guns, learning where to buy bullets, reading about use of weapons in the field, and visiting a shooting range. (If it helps to give a sense of him, as a teenager struggling with ambivalence about his sexuality, he lit a stash of pornography on fire and shot at it while it burned.) It wasn’t long before he lost the awkward unfamiliarity beginners have towards firearms, and learned about other people who had committed suicide with a firearm, and how they had done it.

It’s hard to know for certain, but he was a sensitive guy, and in his worst moments, he must have imagined, over and over, the actions he would have to take to maximize his chances for success, and minimize the possibility for failure. B wasn’t brash or optimistic, and failure must have seemed like a terrible risk to him. If he didn’t succeed, he’d have known the aftermath would be painful and humiliating. This life, this terrible life that he already considered worse than worthless—worse than the nothingness of oblivion—would be marred by a wound in his body, and the loss of trust and respect from his family and friends.

Family and friends would probably have been the hardest thing for him. B must have known that, if he ever succeeded in killing himself, those he cared about would be devastated to learn the bad news. He might consider writing a letter, or even talking to them beforehand. Yet the more he might try to reassure them or share what he had been thinking, the greater the risk of being caught and stopped beforehand. The suicide taboo is so strong in our society that anyone contemplating it is immediately judged to be irrational, locked up, and placed under surveillance in mental institutions. Under these circumstances, talking directly to loved ones won’t work. It’s too risky. Even lingering too long over a suicide note, carefully writing and making revisions, can be a risk.

B’s suicide was ultimately successful, and—as I learned from the comments left online at the funeral home and from talking to our mutual friend, S—extremely traumatic for his family and friends. When B left the world, he did not go cleanly.

A Successful Suicide

I use this phrasing very deliberately. We are admonished never to talk about someone being “successful” at committing suicide because self-proclaimed experts warn us that speaking frankly about it, or ascribing any sane reasoning processes to people who contemplate suicide, encourages more people to die. Thus we must never speak of suicide as anything but a tragedy. Yet the simple fact is that suicide is an action one can attempt, and the attempt can result in success or failure, like any other attempt. Why this insistence on policing our language?

Perry takes great pains to explain that there is a widespread misunderstanding of suicide that comes from assuming suicide is irrational. If suicide is irrational, it’s something that preys upon the irrational parts of us, something stimulated by external circumstances. Thus we must never push people into taking it seriously or acting as though it is something to be successful about.

But what if suicide is rational? What if suicide can be a reasonable response to a painful present and a hopeless future? This is something people don’t like to consider, because it challenges their illusion about the precious sacredness of life. Why maintain such an illusion, even in the face of very obvious misery in the world? Perry’s argument is more detailed than this, but essentially she points out that, by insisting life is sacred, we then give it a sense of purpose and meaning, and that this meaning helps us all to smooth over the things that make life hard. To Perry, it’s acting as though life is worth living that is irrational, and we do this because those who didn’t weren’t the ones who passed on their genes.

Barriers to Suicide

Ultimately, even though it was successful, B’s suicide was nevertheless extremely difficult. He must have known the impact his death would have on the people he cared about. More, over the years I knew him, he was ambivalent about politics and religion, flirting with various political movements and interpretations of the Bible. Although it’s hard to know what exactly his thoughts were, we can only imagine the ambivalence of a man trapped between agony and despair on the one hand, and the fear of eternal damnation on the other.

What emerges from this very brief consideration of just one person’s suicide is how ridiculous and poorly considered is the claim that life must be worth living, because otherwise people would be committing suicide in large numbers. Suicide is frightening. Suicide is difficult—emotionally, technically, and socially. And suicide is very risky. Indeed, the barriers standing in the way of suicide are so numerous and multifaceted, that a person must be miserable, driven, and savvy to bring themselves to make a successful attempt. So the fact that many people don’t fling themselves off of buildings doesn’t prove that they love life; it just means that

they may not be sure which building to jump off of, or when,

they are probably terrified of falling and the pain of landing,

they don’t want to risk being paralyzed rather than dying cleanly,

they may fear God’s judgment, and

they don’t want to hurt their loved ones.

So if low suicide rates aren’t a measure of how worthwhile life is, how can we determine whether life is a good thing for most people, or not?

Is Life Worth Living?

Perry argues that we have very good reasons to believe that life is worse for most people than may seem obvious, and that life is even worse for ourselves than we realize. Evolution, she argues, has a good reason to trick us into passing on our genes whether or not this does us any good. One of the ways evolution has done this is by equipping us with a sense of meaning, when such meaning is, in fact, illusory.

As I read Perry’s work, I initially had trouble grasping what she meant by meaning—possibly because I had been largely inured to the concept even before I encountered her book. Anyone who has ever read the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy should know that when people talk about the “meaning” of life, they are being extremely sloppy. What is the meaning of fork? The meaning of water? The meaning of gravity?

But it quickly became obvious that Perry used the word in exactly the same vague and ill-defined way that most people use it, in the sense that “the meaning of X” entails “some interpretation of X that makes me feel a deep inner satisfaction about it.” In this sense it becomes clear that whenever people ask about the meaning of life, they’re not wondering about it because life is so self-evidently great. They’re thinking about the meaning of life because they feel uncomfortable and ambivalent about life right now, and were hoping there was some kind of positive spin out there.

Perry often avoids thorny philosophical problems in this way, by appealing to the social manifestation of things rather than being concerned about their genuine essence. Ordinarily this kind of analysis leaves me dissatisfied. But insofar as most philosophers have been wandering in circles for the last few thousand years, for Perry to tacitly admit that she’s just going to move forward pragmatically isn’t the worst thing to do. But more than this, it’s clear from the outset that Perry regards knowledge as social in nature, and that she is most interested in pursuing a psychological program—she wants to address Camus’ question: Shall I live, or shall I die?

Even more, she hopes to persuade the reader to allow this choice. So her tools are as much to be found in the empirical science of psychology as in the abstract realms of philosophy. She shows great familiarity with the psychological literature in addressing the question of not whether life is good, but whether people perceive it to be good; not whether life has meaning, but whether people perceive it to be meaningful.

Perry spends a lot of time arguing in the negative: she claims that pain outmatches pleasure, and that while meaning might nevertheless make life feel worthwhile, that meaning is a frail illusion which evaporates under analysis. Her arguments rely on a wide array of economic, sociological, anthropological and psychological facts arranged in extremely clever ways. Although I don’t want to reproduce the content of her book in its entirety, I’ll give one of her arguments because I want to use it as a springboard for observations of my own (and because it’s really fascinating in its own right):

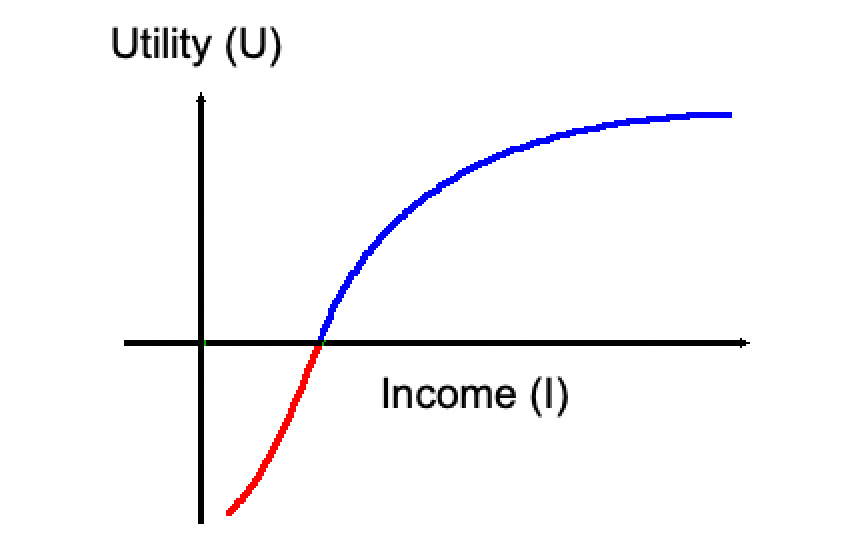

Economists have long noted that, as income increases, people derive diminishing returns in happiness from further increases to income. In calculus terms, this can be stated by saying that the second derivative of utility as a function of income is less than zero, or:

In pictures, we’re just talking about this thing you’ve probably seen all over the place by now:

This curve implies that all people should always be loss averse. Whatever “income” means to you doesn’t matter; Perry thinks the most important factor is likely to be things like social belonging, but we can just as easily treat income directly as a stand-in for material goods. When we do this, we see from this curve that loss should always be worse than gain.

I’ll try to explain what I mean. People who are loss averse, when faced with these three options, will always prefer option 3:

Gamble X to win X with a 40% chance to succeed

Do nothing

Purchase insurance at X which covers losses (beyond the X spent) up to 100 X

Whether we’re talking about apple pies or dollars, option 2 has an expected value of zero; options 1 and 3 have expected values below zero, meaning that if you take option 1 or 3, your income will be worse on average than before. But option 3 is still better than the others. Because the utility function is concave downward, the loss of utility is greater with a loss of X income than the gain in utility with a gain of X income. Thus, we’re better off to accept a small loss than to risk a large loss. This is what is meant when we say people are loss averse. (Chimpanzees are the same way; they’re often unwilling to trade something they have for something they are known to prefer.)2

And yet—and yet! We live in a world where many people persistently prefer option 1. In fact, they are so willing to risk what they have for the prospect of future gain that they will seek out gambles with a negative expected value, just like option 3. I have good experience with this; as a kid, I set up a gambling booth at school; rolling a ten-sided die for the chance to win eight times what you bet was a popular past time. Expected value was negative, but people rolled all the same.

Why?

Well we may imagine this just means they were stupid, or nuts, or something. They were just grade-schoolers, anyway. Probably the fact that they were able to play with a spiffy die is also in there somewhere. But there’s something missing from the narrative up to this point. We’ve drawn a curve, and made some inferences from it to guide our thinking.

But this is what Perry has to say about that curve:

The utility function pictured above has a lot of space beneath it and the x axis, even at the origin. This reflects a judgment that even at zero income, a person takes great value from being alive.

This may or may not fit the facts.

The actual points at which the actual human utility functions intersect the x axis may be far to the right of the y axis, as with this utility function for a person who only begins to get utility at [a certain point]. For all incomes below [this point], the person experiences negative utility—that is, he suffers.

Perry didn’t have color for her graphs, but I do:

For anyone who has ever stared out the window, wishing this could all just be over, we know that this is the real curve, not the other one above. Whatever things a person needs to be happy, there is a point where a person does not get enough of those things. You’ll see this if you start giving them up—your best friend, your job, your home, your pets—you’ll reach a point where you realize you don’t really care if you live anymore. But it can get worse. Keep giving up more things—the rest of your friends and family, a roof over your head, health, a sense of safety, hope for the future, self worth, a sense of meaning—and life is absolutely unbearable.

Suicide is always an option for people living life in the red. Whether the reason they’re in the red is because they lack tangible goods like apple pies (as the graphs imply) or because they lack “income” in terms of more relevant things like social belonging, meaning, or freedom from anxiety doesn’t really matter to them. Because as they know well, when life gets rough, well, you can always kill yourself.

At this point, Perry doesn’t describe things very clearly; she continues to write about utility when she means expected future utility, but I’ve corrected this in the graph below. Her idea is that as long as someone can always kill themselves, they will behave as though they do not fear loss at all. If life is bad now, who cares if it gets worse so long as you can always kill yourself? Thus in the future, the red portion of the graph is truncated, creating a corner where the graph is concave up:

So look at the situation at the flat portion to the left. Should those people be loss averse? Far from it—they have every reason, rationally, to completely discount loss and focus only on the possibility for gain. Now it starts to seem obvious why people don’t only gamble, but become addicted to gambling as a compulsive escape from their dreary lives.

More: when you look at the research, it becomes clear that there are a whole host of seemingly irrational behaviors not only related to disorganization and disagreeableness, but to a person’s tendency to experience anxiety, anger, stress, depression, and other negative emotions—alcohol dependence, drug use, aggression, and conduct disorders all correlate with these miserable feelings.3

For many people, those miserable feelings are a constant companion, a seemingly inescapable feature of their reality. And so they drink, or use drugs, or act out in a hundred other little ways that sacrifice a future they don’t want, to make life bearable for a little while in the present. They aren’t committing suicide, because suicide is hard. Instead, they’re saying no to life right now, day by day, and waiting for it to all be over.

How Many Would Rather Not Exist?

Even though the normal or expected human behavior is loss-averse, there is a subset of people out there for whom behavior frequently looks as though it’s completely inured to loss. Some of these people probably do just lack impulse control, and throw caution to the wind without feeling any suicidality at all. Life is still worth living for them. Others may experience a combination of a sudden dip in their sense of happiness along with a momentary lapse of control which leaves them feeling a little embarrassed afterwards. For these people, life has its ups and downs; we’ll grant that they probably feel life is worth living as well, at least overall.

But there is another sort of person, for whom tragedy has swallowed everything, and life truly holds no joys. “Hit me with whatever you’ve got, world—I don’t care anymore.” He lives his life simply because suicide is difficult, and because he isn’t quite sure that life will always be dreadful, and that there is absolutely no hope at all, ever. Perhaps life will surprise him. Perhaps one of the many gambles he makes will, one day, pay off. And until then, like Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf, he carries always his hidden escape in mind.

How many people like this are out there? Perry doesn’t try to estimate it, because she doesn’t need to; as we’ll see next time, her argument against bringing more people into the world doesn’t require life to be miserable for everyone. But I feel better having some kind of numbers to go by, even if they’re very rough.

So I poked around a little bit in the research on subjective well-being, and found a recent set of American studies4 where a few hundred respondents were asked how much, on a scale of 1-7, they agree or disagree with statements like “I enjoy life.” Generally, respondents agreed (average = 5.015, SD = 1.03). But the spread was such that something like 2% of them were answering with a 3, “slightly disagree,” or worse to this question. Assuming this is representative, then something like 2% of people experience life as a burden. (If this 2% we’re talking about is you, then I am sorry.)

And that’s enough: Sarah Perry’s argument is that to risk creating another person who will experience life as a burden is reckless and immoral.

We’ll explore this position more next week. Until then, take care. I can’t vouch for where I’ll be years and years from now, but if it’s still 2023 when you read this, and you want to talk about it, I’m right here.

And most of my readers probably think of me as a weird cartoon do-gooder who goes around in an apron and carries a rolling pin. The reality may be that I wear mostly black, with boots and a scarf, but don’t let that get in the way of whatever you’re thinking as you read this blog.

Hopper, L. M., Lambeth, S. P., Schapiro, S. J., & Brosnan, S. F. (2014). Social comparison mediates chimpanzees’ responses to loss, not frustration. Animal cognition, 17, 1303-1311.

Settles, R. E., Fischer, S., Cyders, M. A., Combs, J. L., Gunn, R. L., & Smith, G. T. (2012). Negative urgency: a personality predictor of externalizing behavior characterized by neuroticism, low conscientiousness, and disagreeableness. Journal of abnormal psychology, 121(1), 160.

Lui, P. P., & Fernando, G. A. (2018). Development and initial validation of a multidimensional scale assessing subjective well-being: The Well-Being Scale (WeBS). Psychological reports, 121(1), 135-160.

I need to read that book. But not having done so yet, may I ask why it is important to you that your children have access to it?

I always thought of suicide as a way of doing something. People always need to do something (otherwise they will give themselves electric shocks, as we all know). Some people just can't find anything constructive to do in their current situation. So they plan their suicide. Some of them go through with the plan and some of those really die from it.