Long-time readers know I‘ve been thinking very hard about how to fix philosophy. In a previous post, I suggested the principle of non-contradiction is a ray of light shining in the darkness, and Eugene Earnshaw responded by reassuring me that non-contradiction is already very widely used throughout philosophy. Unfortunately, I am not at all reassured that philosophy works.

New readers might find it odd that I’m so skeptical about philosophy. To substantiate my position, I could easily cite philosophers like Stove who’ve argued quite eloquently that philosophy as a discipline (and really, the entire human race) is mad.1 I could go on to cite Lorenzo Warby who explains why: philosophy lacks tests that tether it to reality, “which makes it very easy to wander off into grandiose nonsense.”

But ultimately if we want to establish how successful philosophy has been, the best way is to avoid citing philosophers entirely. The proof, unfortunately, is in the pudding: After thousands of years, we are no closer to a consensus on very simple questions, like, “Does beauty exist?” I don’t need philosophers to be able to measure beauty the way physicists measure the age of the universe, or produce beauty the way chemical engineers produce polymers. If philosophy were anything like science we’d have both of those things by now, but frankly I’d be happy just to know whether things like God, or morality, or beauty, even exist. And I’d like to approach an answer to some of those questions soon (read: ever, before I die) and so I hope that I can be forgiven for failing to sit patiently and let philosophers waste another 2500 years trying to resolve them for me. I’d like to figure out some methodologies or tools, like the principle of non-contradiction, to solve them myself.

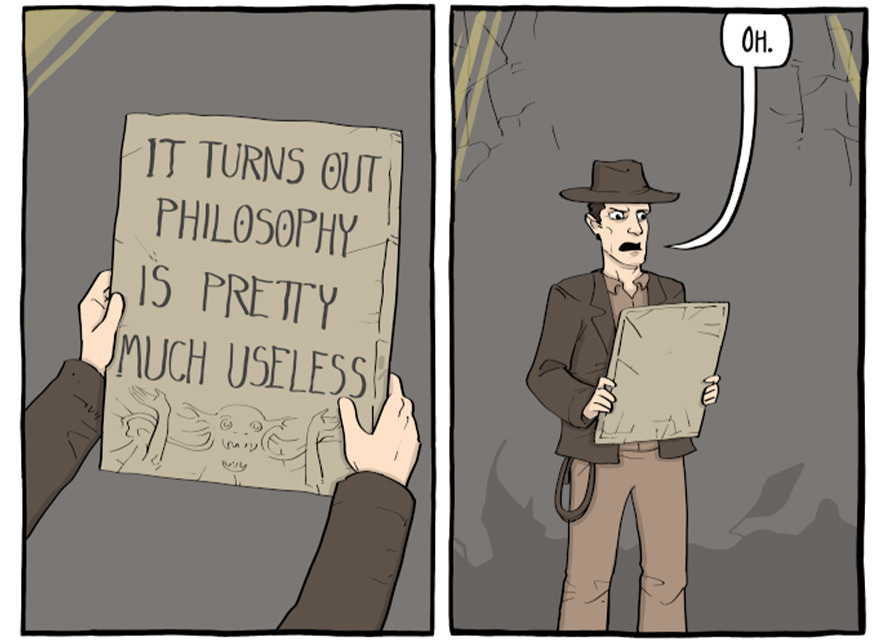

Unfortunately, if philosophy is largely a residuum of failure, and, if philosophers have been using the principle of non-contradiction since Aristotle, then some might say this gives reason to suspect that non-contradiction could be a dead end. Right? If a schizophrenic homeless person comes up to you and explains she’s been taking cariprazine to quiet the demonic voices that follow her around as she’s dragging her shopping cart along the river, you might well suspect that cariprazine doesn’t work very well. Granted, maybe she’d be much worse without it. Maybe she’d be in the river, chasing demons around. But she’s not a very good success story for cariprazine, any more than philosophy is a good success story for the principle of non-contradiction.

Now, science and mathematics actually do give good reason to think non-contradiction is really, really good. Mathematicians in particular have been making successful use of the principle for millennia. Unfortunately the success of science and mathematics may just indicate that chemistry, sociology, and set theory are realms without contradictions, where we can see that, if we ever encounter a contradiction, that really just means one of our assumptions or steps was wrong. But how do we know that living, breathing contradictions do not lurk within the fields of ethics, or aesthetics, or metaphysics? How do we know there are no such things as dialetheias?

Dialetheias

A dialetheia is a Janus-headed monstrosity, both true and false. That such horrors have even been conceived in philosophy might very well be taken as evidence for the peculiar madness of philosophers. L Scott Urban pointed out of dialetheism that “It seems like one of those ideas that accidentally make the thinker stupider, long-term,” and unfortunately that seems fairly typical of philosophy in general.

Philosophy. n. That field of inquiry, or any associated discipline, which makes you stupider in the long term

Still, however damaging dialetheias may be to the intellect, in fairness I must admit to a certain fascination for the creatures. Like ghosts or UFOs, dialetheias have never been convincingly captured on film, but rumors persist regarding their existence, and entire fields of logic have been devised to safeguard against the threat they present to sane and ordered thinking. Unlike an ordinary monster, there can be no hiding from a dialetheia, no way to sneak past it while it is distracted, no hope of eluding an aberration with eyes in the back of its head.

Yet the primary difficulty with dialetheias is actually discovering them, not avoiding them. Non-philosophers who hear about them largely dismiss them as ridiculous, and sensibly ask questions like:

Can anyone provide a contradiction which could not easily be interpreted to be a matter of imprecision of language, or to concern primarily speech acts and the like, or to reduce to the Liar Paradox, and therefore plausibly… be simply accepted?2

Or:

Can anyone provide a good reason why Dialetheism (or paraconsistent logic, in which contradictions may arise without trivializing truth) is expedient, even if one does not believe that there are statements which are in fact true at the same time as their negations are?3

Yet arguments of this form are not particularly reassuring. “We haven’t found one yet” isn’t strong evidence against their existence, and “Believing in dialethias isn’t expedient if we can’t find any” at best just tells us to forget about them.

Aside from self-referential claims, every statement we know of, like “4 + 4 = 8,” or “I’m eating an orange right now,” or “Vladimir Putin will die some time in 2030” is either true or false. Statements like “zebras are black and white” are not contradictions; a proper dialetheia would take the form “zebras are white,” and be both true and not true in the same sense at the same time.

Can This Ever Happen?

Well, philosophers often talk about truth-makers as things floating around in reality which that make statements true or not.4 If we talk about how “The tip of the Statue of Liberty is over 90m up from the ground,” then the height of the statue measured from the ground is a relevant truth-maker for that statement—the thing that makes the statement true. If I talk about how “Not all toilet paper is white,” then these examples right here are the things that make my statement true:

So far so good. But as has been pointed out by two 21st century philosophers, Boccardi and Perelda, if there were ever any truthmakers that contradicted one another, then, a dialetheia would result:

We have argued that a much more promising ontology for dialetheism… is one according to which the world is overdetermined by containing mutually incoherent facts. In our terminology, these facts are in material opposition but not in existential opposition: they do determinately coexist. Material oppositions can obtain either between positive facts (as is the case in Fine’s Fragmentalism), or between a positive and a negative fact (as in Priest’s account of motion if one adopts his polarity view of negative facts)… Dialetheism lives and dies with the prospects of a positive account of negative truths.5

Although I’m not going to review the entirety of their argument, it seems to me rather pursuasive. So, what about negative truths?

If we talk about how “a store contains no rolls of colored toilet paper,” a natural question is, “where is the truth maker for that statement?” There’s no toilet paper there, so there’s no actual object making the statement true. Clearly there could be a truth-maker for a statement about how “there is a roll of colored toilet paper in the store,” because any non-white roll of toilet paper in the store would make that statement true. But can there be a truth maker for the statement “there is no roll of colored toilet paper in this store?”

Personally, as soon as I start thinking about this, I immediately consider the way I could write a computer program that could check the truth of the statement “This store contains no rolls of colored toilet paper:”

TruthValue = 1

for x in ContentsOfStore:

if x == “toilet paper”:

if ColorOf[x] != “white”: TruthValue = 0

if TruthValue: print (“TRUE, this store has no colored toilet paper”)

else: print (“It is FALSE to say that this store has no colored toilet paper”)And obviously there’s no possible truth-maker for the negative statement “there are no rolls of colored toilet paper in the store,” only possible false-makers (i.e. facts that could falsify it.) If you follow through the process above, we start off in the first line by saying the statement is true, and only make it false by finding non-white toilet paper in lines 3 & 4. Yes, there is a possible truth-maker for the statement “there is colored toilet paper in the store,” but this only reinforces the classical idea that if a proposition P has a truth value, then its negation, ~P, gets the opposite truth value for free: Truth(~P) = 1 - Truth(P). We know computer programming works, and this is the way you’d do it with a computer program, ergo, this is how it works in reality.

I’m consciously using a style of argumentation that’s a bit rough—I’m really hugging the safe and reliable STEM fields I know I can trust, and the argument looks a lot like “Computer programs are real, and I see no negative truth-makers there, so in that part of reality that corresponds to algorithms reducible to computer programs, there are no dialetheias.” Unfortunately, reality isn’t always just the set of things that can be reduced to algorithms.

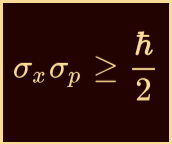

What if we turn to physics? Ironically, perhaps, Quantum Mechanics provides some hope with the uncertainty principle:

The well-known meaning of this principle is that if we know a particle’s position to arbitrary position, we cannot know its momentum; if we know its momentum to arbitrary precision, we cannot know its position. Einstein famously despised this, insisting God does not play dice. Yet the very indeterminacy that so frustrated Einstein may provide an escape from the threat of dialetheias. Boccardi and Perelda concluded that dialetheism requires reality be overdeterminate, but the obvious implication of the uncertainty principle is that reality is underdeterminate, at least in some areas, for some quantities.

Unfortunately, that limitation merely pushes dialetheias out of some corners of physics. We really should have suspected they didn’t exist there anyway, since the sciences are realms where contradictions are not allowed. Ideally, it would be extremely helpful if we could vanquish dialetheias from philosophy.

Now the field of philosophy does provide elegant ways of demonstrating that there are no negative truth-makers, such as the one Saenz gave 2014:

Consider then the smallest of all worlds, the empty world, where no concrete thing exists, and the following list of truths in the empty world: <There are no Martians>, <There are no hobbits>, <There are no humans, rocks, chairs, and houses>, etc. If the empty world were actual, if there were no concrete things, then it would be true that there are no Martians, no hobbits, and no humans. But in the empty world, what entity plays the role of making all these truths true?6

I really like this argument. Obviously no entity can be a truth-maker in an empty world, since there is nothing in the empty world to be a truth-maker. I would argue further that there are no false-makers either; in the empty world, “There are no Martians” is true because no Martian could be found to make it false.

The trouble I have with arguments like this is that they prompt rejoinders that are hard to deal with. Consider Trivialia, a vast and variegated trivialist world where everything is true and false because of a single truthmaker we’ll call Old Nick. In Trivialia, Old Nick has the metaphysical power to make sentences true and false, which he does without hesitation for all sentences. Every sentence in Trivialia is a dialethia, in a sense, because at its core, every sentence is about Old Nick.

Please do allow me apologize for inventing Trivialia—I’m sorry if I’m making myself stupider, and you along with me, because I really don’t want dialetheias to exist! But there is a reason I proposed this world, which will become clear as soon as I ask this question:

Is reality closer to the empty world, or, is it closer to Trivialia?

At first glance, reality is not really like the empty world, because the world we live in is, so far as we can tell, infinite, and absolutely brimming with strange and colorful things. If we had to pick, our world looks more like Trivialia. Remember, Trivialia is vast and variegated, and full of things to talk about, just like our world. “Is frozen yoghurt any good?” “Is Donald Trump literally Hitler?” We can (and do) say both yes and no to these statements, quite regularly. So our world actually looks like Trivialia, and the conclusion we can draw from this similarity is that there are dialethia, and maybe, they are everywhere.

Like most sensible people, Saenz obviously doesn’t want this. He wants our world to be like the empty world, just… not empty. He wants us to learn something about our world by imagining that it were different. But the empty world is extremely different from reality, not only because there are absolutely no things there, but because of what follows from that nothingness: Nobody can even speak the sentences we would like to be true or false in the empty world. All sentences about the empty world have to originate from outside of it, whereas all sentences we know of about our world originate from within it.7

Trivialia, in contrast to the empty world, is full of sentences, exactly like our own world.

Of course there are rejoinders to these rejoinders that might be able to expose their sophistry. But unfortunately that’s all they are, just rejoinders. They never end; they just lead further and further into the swamp.

A Way Out

So far, this is the way philosophy has always been: A world of ideas going back and forth, spiraling deeper and deeper without consensus, because the philosophers’ toolkit isn’t like the toolkit of mathematicians or scientists; there is no reality test there, no clear method by which the truth can be revealed. And if ours is a world where dialetheias exist, even the principle of non-contradiction is useless for showing us the way.

But in fact, I do believe that I have found a way to escape from this swamp. The trouble, of course, is to clearly explain it, but I’ll try to post what I’ve figured out soon. In the meantime, it’s useless to deny that this is where we have been floundering for millennia. Better to at least admit that, if we must go wandering away from the safe shores of scientific empiricism, it would be very good to have some protection from the abominations lurking deep within the darkness of philosophy.

Stove, D (1991). The Plato Cult and Other Philosophical Follies. Blackwell. (See https://web.maths.unsw.edu.au/~jim/wrongthoughts.html)

De Beudrap, N. (2011). Motivations for dialetheism? Philosophy Stack Exchange.

Ibid.

Mulligan, K., Simons, P., & Smith, B. (1984). Truth-makers. Philosophy and phenomenological research, 44(3), 287-321.

Boccardi, E., & Perelda, F. (2020). What it is like to be a Dialetheia. The Ontology of True Contradictions. Eternity & Contradiction Journal of Fundamental Ontology, 2(2), 116-162.

Saenz, N. (2014). The world and truth about what is not. The Philosophical Quarterly, 64(254), 82-98.

Yes I’m avoiding solipsism which is another monster I can’t fight right now because I have my hands full trying to deal with the dialetheias.

Can't wait.

Are you going to have any diversions on the way? The tetralemma for example.

Still feel 'model collapse' is a good analogy for metaphysics, and "model collapse" in LLMs etc is reached by entirely electro-logical means. Dialetheias is just a bad Janus dancer.