What if the Octave had 19 or 31 Notes?

Xenharmonic Music

Growing up, I loved musical modes. These are scales you get just by picking a white key on a piano and going up the scale without any of the black keys. Modes have ancient Greek names like Ionian and Mixolydian; and my favorites were Aolean, a classic harmonic minor starting from A, and Phrygian, which starts from E, and thus has a lowered 2nd step common to most metal music.

I still use modes; listening to this piece I made in Aeolean, you can tell I liked the Splatterhouse series when it came out.1 (You can edit this song for yourself; in case you get stuck listening to it over and over, drag the purple slider to the end and then stop it. Or, you know. Try it over and over in D# the way its creator does.)

But the subject of scales is much broader than this. If you’re willing to leave the familiar realm of ordinary scales behind completely, and divide an “octave” up into 5, 7, 19, or 31 notes, you’ll find you’ve entered the bizarre new world of xenharmonic music.

Macrotonal Xenharmonic Scales

The idea of music made using, say, a scale of 9 equal divisions of the octave (9 EDO) is very interesting, but how does it sound? Well unfortunately—and don’t take this the wrong way if you’re a composer in the macrotonal world, but unfortunately—many of these scales will make a person’s ears bleed:2

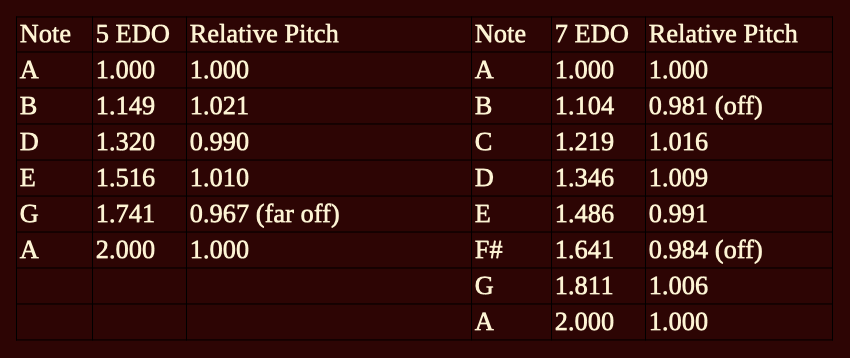

There’s a clue to be found by wading through the above, though: All the notes in scales dividing the octave into 2, 3, 4, and 6 equal divisions already exist in a regular scale, and don’t really provide any new options. Then 8 through 11 are terrible, with 11 sounding particularly stupid. But dividing an octave into 5 notes, or 7 notes, creates strange new sounds that almost work. The reason for this is that these are prime numbers far from 12, and some of the notes approximate a 12-note just intonation:

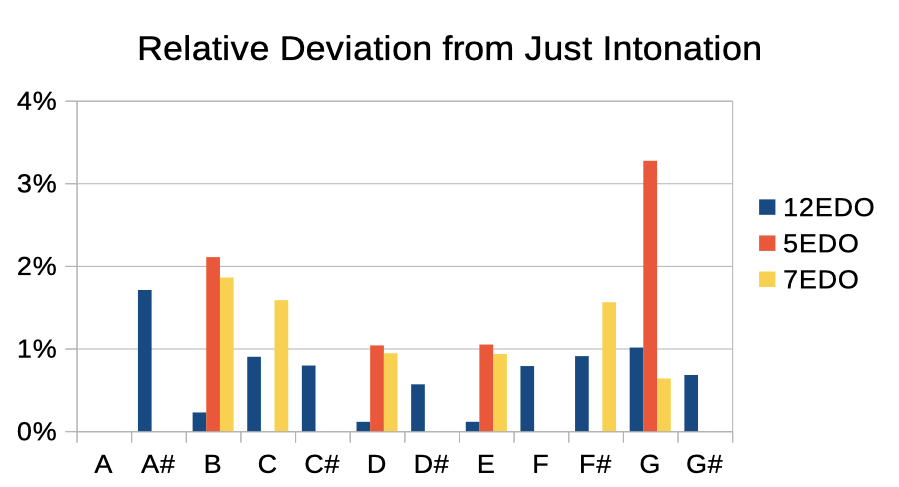

Even the usual 12 equal divisions of an octave—that is, 12 EDO—doesn’t perfectly match doesn’t perfectly match just intonation. We use it because an instrument has to be tuned to a specific key in just intonation, and then it won’t work for other keys.3 If you’re not familiar with tuning, I’ll try to sum it up by saying that sound is all about vibration. The plucking of a single string actually produces a multitude of subtle harmonics along pure fractional ratios. These fractional ratios are what make up the different notes in a scale tuned according to just intonation, and aren’t evenly spaced, so even 12 EDO doesn’t hit all the notes in a way that perfectly matches the harmonics. But how well do xenharmonic scales match just intonation? To give a sense of how accurately these different scales reproduce familiar music, I compared their frequencies to the regular 12 EDO:

The typical distance between half-steps in just intonation is around 6%, so the “G” from 5 EDO really splits F# and G, and the B sounds odd in both 5 EDO and 7 EDO—enough that those are notes that would ordinarily sound far out of tune in a conventional context.

For all this, however, you can definitely make music with these xenharmonic scales. Although I do like the 12 EDO original better, Olivia Jageurs did a very good job with Matthew Sheeran’s Lyres of Ur in 7 EDO. Unsurprisingly though, songs are better if they’re composed in these xenharmonic scales to begin with, and Amano Hideya’s Like Japanese Curry is a very good example of 5 EDO music, with a kind of amelodic feel:

These songs aren’t wonderful, but they do at least have musical merit. The main problem with macrotonal scales is that the limited number of notes creates a very restricted auditory palette. This is why things don’t get really interesting until you start looking at microtonal xenharmonic scales that divide up an octave into more than 12 notes.

Microtonal Xenharmonic Scales

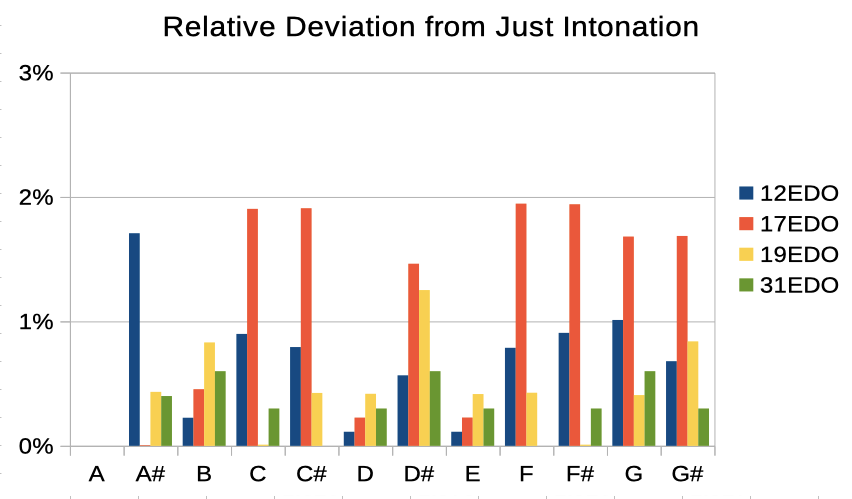

Mathematically we could divide an octave into any number of notes, like 50, or 300, or 21.991 (that’s about 9 π), but they aren’t likely to sound good, or even produce tones that we can tell apart. Are there really any microtonal scales that can do a better job than the classic 12 EDO, though? Well predictably 13 EDO is awful, and 16 through 18 are not great. But then we find 19—another prime number that avoids being too close to any multiple of 12—gives us a very exotic sound without being musically confining.

It requires a bit of nuance to make music that takes advantage of the additional notes in EDO 19 without descending into a cacophanous mess (like this rendition of Carol of the Bells). Nevertheless, it can definitely be done—Exhibit A here is Cat Logic, by Stevie Boyes:

Because it divides the octave up so finely, 19 EDO produces notes close enough to a regular scale that it can still be used to make ordinary music, like Love Shines Through - Stevie Boyes, Dove - Antihoney, Anthems for a Seventeen Year‐Old Girl - Broken Social Scene, or the baseline to Metallica’s Enter Sandman. This is why 19 EDO has been called “the stealth microtonal tuning.” The most dissonant note is D#, which does end up a bit high in pitch, but in general the 19 notes in 19 EDO actually reproduce the 12 notes of just intonation slightly better than the usual 12 EDO:

Notice, however, that just having many divisions doesn’t guarantee a good match for the classical scale. 17 EDO is slightly shifted so that, as shown in orange above, most of its notes lie in between the classic notes. The resultant scale gives rise to pieces like the aptly named Ephemeral Happiness—if you give it a listen, you’ll find happiness lasts for only 24.8 seconds in 17 EDO.

Once you train your ear a bit with 19 EDO, though, you can appreciate stranger songs like Lagoon, Diester’s Saccarine Song, or The Future is No Longer Accessible. Although there’s very little out there that’s been written in 19 EDO, the seven additional notes allow for sub- and super-major chords, as well as another option in between perfect and diminished fifths, and even an extra note nestled just below the tonic. The most obvious ways I can think of to make use of these additional notes would be with trills, or by swapping out adjacent notes in repetitive arpeggios, but really broadening into the space would require chord progressions that are wholly absent from classical music. You can probably tell I’m captivated by this scale—I actually find that the 19 EDO Carol of Bells I mentioned above gives me chills at this point. (On the other hand, that may just go to show that I’m pathalogically high in Openness and fried out my musical palette with xenharmonic music, IDK.4)

And then there are even more finely divided microtonal scales, like 31 EDO.

Most xenharmonic scales don’t work very well because few of the notes match just intonation. But the more divisions you have, the more options there are, and 31 EDO is another xenharmonic scale that divides the octave into equal parts using a prime number far from a multiple of 12.

31 EDO gets a lot of love from the musical community. Chances are, if you want to find microtonal music in other scales your search results are going to be innundated with 31 EDO songs.

Unfortunately, I really think the granularity of 31 EDO is excessive—and making good use of the additional notes does indeed appear to be harder here than in 19 EDO. You should probably browse around for yourselves and see what you think, but frankly there’s a lot of music written in 31 EDO that I suspect exists primarily as a vehicle for intellectuals to impress one another by ignoring how random, meandering or miserable it sounds.

Yet good music can definitely be composed and played in EDO 31. Here’s You’re Everything, by Vogelgeorg:

And although the more typical 31 EDO music does tend to meander, I definitely enjoyed Glitterdance, by Zhea Erose, and Mike Battaglia’s 31 EDO rendition of Scarborough Fair.

I think it says something about the kind of person who’s drawn to these odd scales that there’s so much light xenharmonic jazz. Jazz itself has always tended to push against the limitations of a classical 12 EDO scale, and while personality correlations with music preferences are quite weak,5 we do find from a massive study of over 5000 Spotify users that jazz is slightly more preferred by Conscientious, Agreeable, Open people,6 so this is kind of what there is so far—a bunch of xenharmonic music that would appeal to the cast of Star Trek, The Next Generation.

To me, though, most of the music that currently exists in this sphere comes across as either awful, or else, dry and unmemorable because of how little structure or pattern there is to be found. And this is really striking to me, because this isn’t what I expected at all when I first found out about xenharmonic music.

Doesn’t the term xenharmonicity itself evoke the strange and unsettling? I think musicians have been slow to appreciate the opportunity to create weird, frightening, and angry music using the dissonance available in xenharmonic scales. I realize most of my readers may not have heard of xenharmonicity, and so presumably most musicians are in the dark, too. But this stuff is not new. It’s been around since Chalmers wrote about 19 EDO in the 1961 edition of Current Musicology.7 Before that, Joseph Yasser promoted 19 EDO in his 1932 Theory of Evolving Tonality.8 And before that, Guillaume Costeley used it in the 16th century to compose his Seigneur Dieu ta pitié:

So all right, what about after that? After all of these centuries of theory and experimentation, where have xenharmonic scales gone? Well, so far as I can determine, it’s mostly been a bunch of jazz musicians using it to make a bunch of music that, you know, sounds like jazz.

But I’m not interested in xenharmonic scales because I like jazz. I’m interested in xenharmonic scales because I think they have potential for darker genres. I love the chilling synthwave remixes Luminist composed for the Metroid Theme and Kraid’s Lair; how would those have sounded in 19 EDO? Sure, we do have great Arab Metal that makes use of quarter-note tuning on the Oud. But why so little beyod this? It’s like metalheads just discovered Phrygian (or maybe, ooh, Phrygian dominant) and called it a day. The fact that there isn’t yet much good xenharmonic metal suggests there’s an opening here. I’m no good with guitars, so I’m not really going to be the one to exploit this opportunity, but guys, seriously listen!

This is

how metal

Granted, it does technically veer out of Aeolean with the glissando at the end of the first measure, but it’s pretty subtle

This may be related to the phenomenon where people use lay instead of lie. I know, I know—after a long day you really “feel like laying down,” or you don’t want to be bothered when you’re “laying in bed.” Or hey, maybe you just want your dog to “lay down and go to sleep,” but please people, seriously, think of my ears.

It even gives dissonance within a single key if you try to create a chord using the wrong notes, like a D-minor chord (DFA) in a C-major scale tuned to just intonation.

Colver, M. C., & El-Alayli, A. (2016). Getting aesthetic chills from music: The connection between openness to experience and frisson. Psychology of Music, 44(3), 413-427.

Schäfer, T., & Mehlhorn, C. (2017). Can personality traits predict musical style preferences? A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 265–273.

Anderson, I., Gil, S., Gibson, C., Wolf, S., Shapiro, W., Semerci, O., & Greenberg, D. M. (2021). “Just the way you are”: Linking music listening on Spotify and personality. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(4), 561-572.

Chalmers, J. (1967). Mayer Joel Mandelbaum: Multiple division of the octave and the tonal resources of 19-tone temperament. Current musicology, (5), 138-142.

Joseph Yasser. (1932) A Theory of Evolving Tonality. New York.

You might also be interested in the Turkish classical music makam system, which divides the octave into 53 (another prime number) equal intervals known as commas. The wikipedia article is pretty good.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Turkish_makam

It's interesting and it seems to come up every few years on YouTube. It's cool in principle, the idea of new things like the super major and so on, but I've never heard one thing worth listening to come out of it. Not really.

I don't think so anyway. There might be ambient track that made use of microtonal well. Not sure, might have. But there's a reason Western harmony went the way it did and not that way. And it's not just cultural conditioning. It's something hard wired about what makes sense and where the action is, and excluding where the action isn’t.