Politika

Tough Mindedness is a basic dimension of Political Values

I’m running a survey on romantic preferences, but I’m having trouble getting female respondents. If you or someone you know happens to meet that description, and it’s still March of 2025 when you read this, consider helping me out with the Romantic Preferences Survey!

Lately I’ve gotten a lot of interest in political values, so I thought I’d offer some of the extensive data I have on politics. Even though I grew up in the 80’s and 90’s, before American politics was the minefield it is today, my parents and their families were bitterly divided politically, and I’ve been navigating the conflicting social spaces of the left and the right from a young age.

Most Westerners are by now familiar with the idea that there is more to politics than just left and right. However, the second largest dimension, after conservatism vs leftism, isn’t libertarianism—rather, it’s another dimension, called realism, pragmatism, or, traditionally, Tough-Mindedness vs Tender-Mindedness.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, tough-minded attitudes have become generally taboo. Hans Eysenck, the psychologist who did most to drive this research paradigm forward, was deeply embittered towards the fascists and communists responsible for not only the deaths of millions worldwide, but the loss of his maternal grandmother to a Nazi concentration camp.1

Yet while I have been able to personally verify the thrust of Eysenck’s findings, the tendency to smooth over complexity has relegated a huge swath of ideas—true and false, good and bad—to the realm of the twisted and perverse. Yes, it is true that Eysenck and his contemporaries successfully established that tough-minded groups display more dominance and aggression than controls. And this finding is still true today, as I’ll show from my own research. However, while Eysenck was a signatory of the Humanist Manifesto, his own beliefs were never monolithically tender minded. He argued that ethnic gaps in intelligence had a genetic origin.2 He promoted the use of harsh punishment to curtail criminality.3 He even resisted admitting a direct link between smoking and cancer, writing that “simplistic formulations like ‘Smoking causes cancer’ have no part to play in the scientific study of this disease.”4

I’m not arguing Eysenck was right about any of these stances; but I do want point out that something has been lost since Eysenck died. More than anything else Eysenck ever wrote, what always endeared him to me were these lines in his autobiography:

I always felt that a scientist owes the world only one thing, and that is the truth as he sees it. If the truth contradicts deeply held beliefs, that is too bad. Tact and diplomacy are fine in international relations, in politics, perhaps even in business; in science only one thing matters, and that is the facts.5

For their time, these were hardly unusual ideas, but in the conext of the current tender-minded millieux they take on a much sharper flavor. While I’ve reluctantly learned that tact does matter, even in science, I will ask readers to consider whether they would prefer people deal with them tactfully or truthfully. When tact conflicts with truth, it simply becomes anther word for lies. Put this way, it becomes much harder to argue in favor of politely mouthing the gentle beliefs of the day.

And while the tough-minded may simply shrug off ethical dilemmas and ask whether morality even exists, tender-mindedness has always struggled with facing unpleasant facts. Thus, while I hope that the information I have to share here does clearly reveal the downsides inherent in tough-mindedness, I want to stress that the repression of each and every tough-minded attitude (particularly each and every tough-minded conservative attitude) cannot be in anyone’s best interest.

What is Tough-Mindedness?

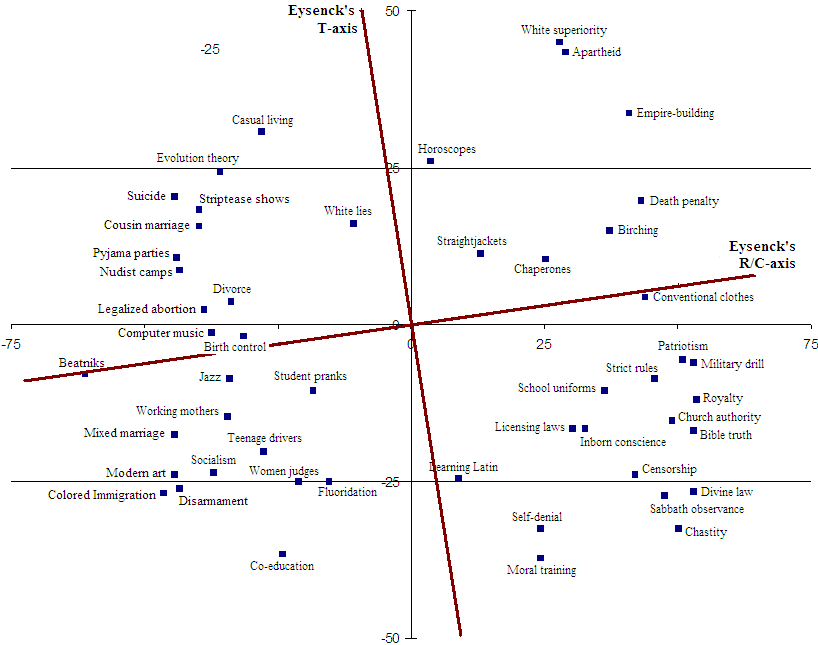

Strictly speaking, Tough-Mindedness is a dimension that emerges from factor analysis of attitude questionaires. Here is a very early result, combining studies from almost a hundred years ago,678 which Eysenck put together in 1944:9

Already we can see the irreligious, sexual, and aggressive character of tough-mindedness with support for divorce, evolution, birth control, capital punishment, and war. Meanwhile the tender-minded favor vegetarianism, pacifism, prohibition, and going to church. Later on, in the 1950s, Eysenck put together a model of politics that attempted to explain what was wrong with the world he had grown up in: communists were on the left, and fascists were on the right, but Tough-Mindedness was the common thread:

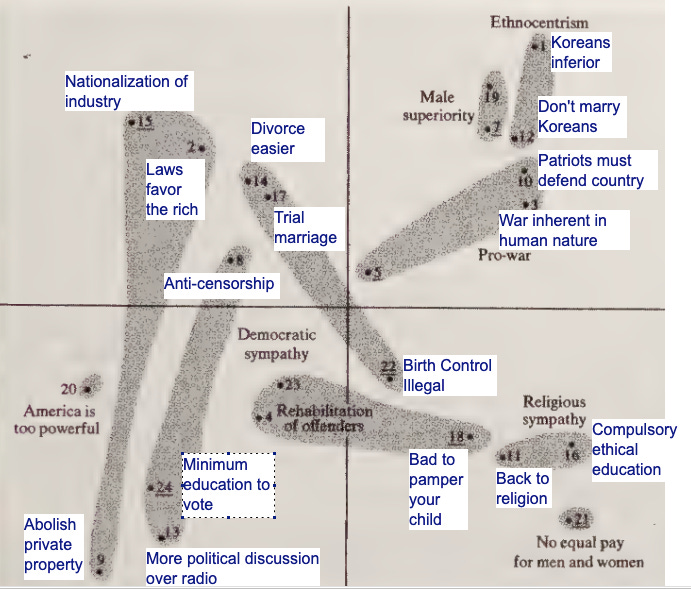

And among his covert studies of fascists and communists, Eysenck found these classic results replicating the way attitudes clustered:10

The results were the same as always: abortion and divorce for tough leftists; ethnocentrism and punitiveness for tough conservatives; pacifism for tender leftists; and religion for tender conservatives.

At the time, Eysenck’s results were criticized for the lack of content in the center.1112 Are there no purely tough- or tender-minded political values? It was over issues like this that Eysenck’s paradigm fell out of favor. This is unfortunate, not only because Eysenck actually anticipated these criticisms by saying that a person must have some political idea to be tough or tender-minded about—but because it was never true that there were no values and attitudes that were purely tough or tender. Twenty years later, in 1973, Glen Wilson carried out his own factor analysis of opinion surveys.13 When the axes are rotated slightly (as shown in red), the familiar dimensions appear:

Even Eysenck’s dissenters, like Stone and Russ, ultimately replicated Eysenck’s findings. Though they insisted that Tough-Mindedness was merely Machiavellianism, and reported a correlation of r = 0.44 between Eysenck’s Tough-Mindedness and Machiavellianism, their factor analysis of Machiavellianism items was quite interesting—not least because of the way it showed what kinds of values might be purely tough- or tender-minded:14

Though it seems to have mostly gone unnoticed, some of my favorite results from Eysenck and others were compiled by James Allen Dator in 1969. His graphs were a bit vague, but they detail the political map for British subjects, American judges, and here, for a sample of 355 male and female Japanese university students, which I’ve annotated in blue:15

The desire for voting restriction at #24 is strange, as is the weak conservative loading on #5—possibly these questions were interpreted in an interesting way. But everything else clearly matches the basic map.

And of course, no one who follows the findings of psychology will be surprised to see that, by 1974, Eysenck was able to estimate the heritability of his two political dimensions in a sample of 700 twins: Conservatism had a heritability of 0.65, while the heritability of Tough-Mindedness was 0.54.

So by now Eysenck’s model had:

Over a dozen independent replications of the basic map,

Replications spanning multiple countries, establishing the dimensions are not limited to one time and place,

A successful prediction regarding the underlying similarity between communists and fascists, and,

Evidence for a heritable, biological origin for political values.

Unfortunately, by the end of the 20th century, Eysenck was getting old. His psychological instruments were weak, he didn’t have convincing links to major dimensions of personality, and his attempts to show how awful tough-minded people were didn’t really dovetail with most psychologists’ desire to pathologize the living daylights out of conservatives. Boomer psychologists were really never on board with Eysenck’s program. The horror of Communism had been largely forgotten by the 1990’s, and “Right Wing Authoritarianism” and “Social Dominance Orientation”16 offered much more promising ways of putting conservatives under a microscope than Tough-Mindedness.

Does The Model Still Stand Up in the 21st Century?

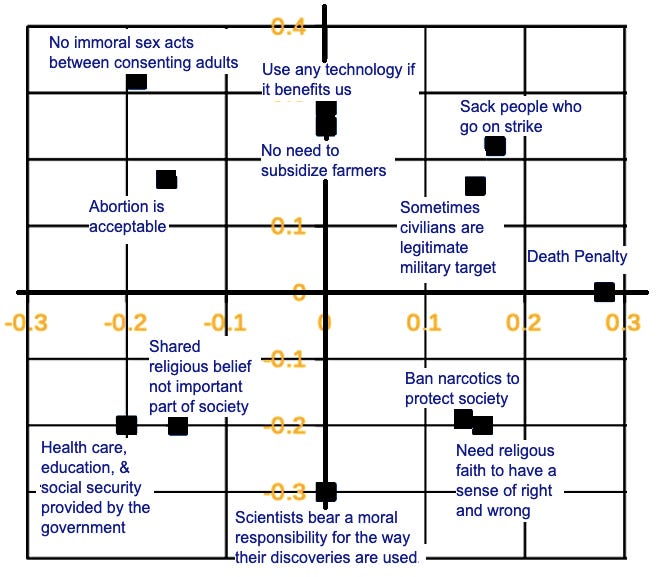

In 2003, Chris Lightfoot created Political Survey, which he described as “an open, honest version of politicalcompass.org.”17 Unlike Political Compass, which started with an a priori notion that libertarianism/paternalism was the important second factor of political values after conservatism/leftism, Lightfoot gave out a battery of questions to people online and determined empirically how attitudes were arranged using factor analysis.

Although Lightfoot’s survey wasn’t specifically designed as a scientific instrument, he wrote his own code to be totally open and subject to scrutiny. Lightfoot found two factors which (apparently in ignorance of Wilson’s and Eysenck’s research) he labeled “left/right” and “pragmatic/idealistic.”

Lightfoot’s survey is the most important since Eysenck’s first paper on the subject and deserves detailed discussion. Lightfoot writes of the first eigenvector: “This axis is quite like the familiar left/right political division. It mixes economic issues—varying from laissez faire to interventionist perspective—and social or ‘moral’ issues such as recommending the death penalty for criminals.” Unsurprisingly, he discovered that most political variation comes down to conservatism vs leftism.

The second eigenvector, however, “It represents a combination of philosophies you could call ‘pragmatism,’ ‘utilitarian,’ and so forth, mixing social, religious, and economic issues. We have chosen to give an atheist, utilitarian perspective positive values on this axis.” I’ve made a graph from his twelve highest-loading items:18

The content of these questions shows that, even today, using a completely unrelated set of questions, we find essentially the same two axes which have been appearing under factor analysis for almost a century.

Considering all of the above, I became interested in seeing whether I could replicate these findings muself. Here are the results from one of the first surveys I carried out online, in 2010, on 100 subjects:

I was also interested in HEXACO personality traits, and in where Right Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) would appear on the map. But more importantly, I wanted to investigate the apparent link these political dimensions had with personality. Eysenck did show aggression and dominance in tough-minded subjects, but he’d never managed to clearly establish how major dimensions of personality relate to Tough-Mindedness. He tried proposing a link between Tough-Mindedness and Extraversion, but as I found out right away, that wasn’t really what was going on:

You can see that the tender-minded side has Agreeableness and Honesty-Humility; Tough-Mindedness is associated with their lack. Obviously the sample size was small, but I replicated the negative relationship between Tough-Mindedness and both A and H on another sample of 100; the positions of the personality traits was essentially the same (though Agreeableness no longer fell on the left). My most recent replication had 301 respondents, and gave the same basic pattern: Conservatives are higher in Honesty and Conscientiousness, Leftists are more Open, and the Tough-Minded aren’t very Honest or Agreeable.

What’s the Conclusion?

Well, the obvious conclusion is that tough-minded people are just bad, and as such, they believe and value bad things. It’s simple: Hitler blamed international Jewry for the problems in the world, Hitler was a villain, so that’s probably evidence for some kind of cause and effect relationship. Right? Stalin read Charles Darwin and rejected God, Stalin was a villain, and here again we see how being evil makes you believe evil things. Or if we need something more current, Dr. Octopus thinks protecting the innocent is weak, and he’s a supervillain, so there you go.

Some of my more savvy readers may at this point detect just the slightest hint of sarcasm. Obviously there’s an argument to be made that bad people believe bad things because of motivated cognition. It’s convenient for a bad person to accept ideas that resonate with them or help them justify their actions.

But if that’s true, then aren’t good people vulnerable to similar tendencies? Even if their values aren’t self-serving, wouldn’t good people want to justify their own intuitions the same way that bad people would? Being honest with other people—in the sense of not stealing, not lying, not being envious, and everything else related to the broad personaity trait of Honesty—might make us better at penetrating the veil that hides reality from our eyes, and confronting the universe squarely on its own terms. It could. But does it? Being Agreeable, in the sense of having patience, forgiving others, and generally manifesting traits associated with Agreeableness, might very well make a person especially good at understanding and accepting the world for what it is. But is that really the case?

When we look at the matter scientifically, what we find is that good people often have trouble seeing the bad in others. One of the most interesting findings of personality research reveals a specific bias that affects people high in Honesty-Humility (H) and Openness to Experience (O): They are likely to falsely assume similarity between other people and themselves.19 In other words, people who are virtuous and imaginative are quick to believe others are like them, even when they really arent. According to a recent meta-analysis, the magnitude of assumed similarity is quite substantial, at approximately r = 0.5 for H and r = 0.3 for O.20 (The study authors speculated that this assumption helps keep couples together.)

So is there any part of the political map where we tend to find high Honesty and Openness? That’s the tender-minded, leftist quadrant. So scroll up, and look at the bottom-left corners of the maps above where high Honesty and high Openness combine. There are many values and beliefs there that could very easily arise from careful, clear analysis of the world as it is. But when I consider claims like “conscientious objectors are not traitors,” “people are good,” “shared religious belief isn’t important,” and “patriotism is a force against peace,” I wonder how much of this comes from the assumption that, deep down, everyone across the world is virtuous and imaginative, just like the median tender-minded leftist. When I see tender-minded leftists insisting that racism is a major problem, that immigration is OK, and that nuclear disarmament is the way forward, I wonder whether it’s because they look at everyone across the world and think, surely, that everyone is basically the same.

But the lesson from all of this is that people obviously are not the same. And the roots of our differences aren’t just the way we’re raised: using the Wilson-Patterson Conservatism scale—the one with the red cross in it, above—a study of over 4000 twins found the variation in people’s answers to different political questions had an average heritability of 0.32, but an average input from the common environment or upbringing of exactly half this, at 0.16.21

We’re all different, not only as a result of the way we’re raised, but deep down. All of these maps are so fascinating to me because they’re the closest we can come right now to understanding that difference—map after map brings us closer to developing a clear picture of the human soul. This is what we are: not the same, but different. And while a gentle and optimistic response to that difference is commendable, the way I’d expect that response to look is less like a series of insults about racism and transphobia, and more like a question:

If you are different from me, what do you see that I don’t see?

Colman, A.M. and Frosch, C. (2017). Why did Britain’s most prominent psychologist deny his Jewish heritage? The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/why-did-britains-most-prominent-psychologist-deny-his-jewish-heritage-84875

Eysenck, H. (1971). Race, Intelligence and Education. London: Maurice Temple Smith.

Eysenck, H. J., & Gudjonsson, G. H. (1989). The causes and cures of criminality. Springer Science

Eysenck, H. J. (1988). Personality, stress and cancer: Prediction and prophylaxis. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 61(1), 57-75.

Eysenck, H. J., Rebel with a Cause (an Autobiography), London: W. H. Allen & Co., 1990

Ferguson, L. W. (1939). “Primary social attitudes.” Journal of Psychology, 8, 217-223

Carlson, H. B. (1934) “Attitudes of undergraduate students.” Journal of Social Psychology, 5, 202-212

Thurstone, L. L. (1935) The vectors of mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Eysenck, H. J. (1944). “General Social Attitudes.” Journal of Social Psychology, 19, 207-227. (Includes unpublished data by Flügel & Hopkins regarding “unorthodox opinions”, N = 700.)

Eysenck, H. J. (1954). The Psychology of Politics. Routledge, London.

Rokeach, M. and Hanley, C. (1956). “Eysenck’s tender-mindedness dimension: A critique.” Psychological Bulletin, 53, 2.

Stone, W. F., & Russ, R. C. (1976). Machiavellianism as tough-mindedness. Journal of Social Psychology, 98, 213-220.

Wilson, G. D. (1973). The Psychology of Conservatism, edited by Glenn D. Wilson, Academic Press.

Stone, W. F., & Russ, R. C. (1976). Machiavellianism as tough-mindedness. Journal of Social Psychology, 98, 213-220.

Dator, J. A. (1969). Measuring attitudes across cultures: A factor analysis of the replies of Japanese judges to Eysenck's inventory of conservative-progressive ideology. In H. J. Eysenck & G. D. Wilson (Eds.), The Psychological Basis of Ideology (pp. 73-104). Baltimore: University Park Press

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of personality and social psychology, 67(4), 741.

Lightfoot, Chris (2003) “Political Survey: an open, honest version of politicalcompass.org.” http://politics.beasts.org/ accessed May 28, 2009.

Ibid

Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Pozzebon, J. A., Visser, B. A., Bourdage, J. S., & Ogunfowora, B. (2009). Similarity and assumed similarity in personality reports of well-acquainted persons. Journal of personality and social psychology, 96(2), 460.

Liu, J., Ilmarinen, V. J., & Lehane, C. (2022). Seeing you in me: Moderating role of relationship satisfaction and commitment on assumed similarity in honesty-humility and openness to experience. Journal of Research in Personality, 97, 104209.

Alford, J. R., Funk, C. L., & Hibbing, J. R. (2005). Are political orientations genetically transmitted?. American political science review, 99(2), 153-167.

I've always been of two minds about surveys; (Self-)deception is just too strong. There is no reason to believe that a person who is lying a lot IRL isn't lying when filling out a survey; Worse yet, there is no reason to believe that person is even honest to themselves or fully aware of the degree of their own dishonesty.

At the current political moment, I see this most clearly when it comes to "combating disinformation". Strictly speaking, who doesn't support that? Yet, I don't. The problem isn't the idea, it's the practice: It's mostly used to shut up inconvenient voices on technicalities, while the favored voices can usually get away with blatant lies as long as they have some fig leaf to hide behind.

This is what I think when I see "honesty" as an item on one side. It's certainly the side that wants (you) to believe that they're honest. Are they? Hard to say. IRL it's not rare at all for the person who says that lies are sometimes justifiable to be more truthful than the person who claims that you should never lie.

In support of the article, I've been saying for some time now that the current left, similar to other idealistic/religious dogmas, has become the side of "sounds nice, doesn't work". What I want is, obviously, "sounds nice, and works". But if that's not an option, I'll rather settle for "works, but isn't nice".

I found your argument thought-provoking, especially your insights on tender-minded projection and the importance of acknowledging fundamental differences in perception and reasoning.

Your call for intellectual humility—“If you are different from me, what do you see that I don’t see?”—is a valuable approach to political discourse.

That said, I think the argument could be strengthened by addressing a few points:

1. Cognitive Biases Exist on Both Sides

You argue that tender-minded individuals assume too much similarity, leading to naivety. But tough-minded individuals are also prone to distortions, particularly negativity bias, which can lead to excessive distrust and overestimation of threats (Hibbing, Smith & Alford, 2014). If tender-mindedness risks naivety, doesn’t tough-mindedness risk cynicism?

2. Political Views Can Change

Your discussion of heritability in political attitudes is compelling, but history shows that ideology is shaped by material conditions and crises:

• Post-WWII Germany & Japan embraced liberal democracy after militarism.

• The Great Depression shifted views on state intervention.

If political beliefs were purely biologically driven, we wouldn’t see such shifts. How do you reconcile personality-driven ideology with historical transformations?

3. Tender-Mindedness Can Be Pragmatic

You frame tough-minded realism as practical and tender-mindedness as naive, yet history shows tender-minded policies can be strategically effective:

• The Marshall Plan prevented the spread of communism without war.

• Portugal’s drug decriminalization led to lower addiction rates and crime.

If tough-mindedness leads to realism, what happens when tender-minded policies outperform tough-minded ones?

4. The Limits of Dialogue

Your argument promotes understanding ideological differences, but not all viewpoints are reconcilable:

• A democracy cannot function if one side denies elections.

• Not all perspectives deserve legitimacy—science denial, racism, and authoritarianism must be actively opposed.

• Bad-faith actors exist—some use political discourse as a weapon rather than engaging honestly.

Where do you see the boundary between productive debate and the need to reject certain ideas outright?

I’d love to hear your thoughts—especially on how you see realism, pragmatism, and ideology interacting.