Is Something Special About Israeli Fertility?

Three straightforward explanations for the Israeli Fertility Rate

It’s common lately for people who don’t understand sociology journalists to remark on Israel’s high fertility:

Israel’s Exceptional Fertility: “Israel’s TFR is the highest among the OECD countries”

Israel Tops Birth Rate in OECD: “Israel has the highest fertility rate among a group of 38 industrialized nations”

Israel’s birth rate remains highest in OECD by far, at 2.9 children per woman: “Israel’s birth rate remains the highest among countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development”

The first of these articles offers the following graph:

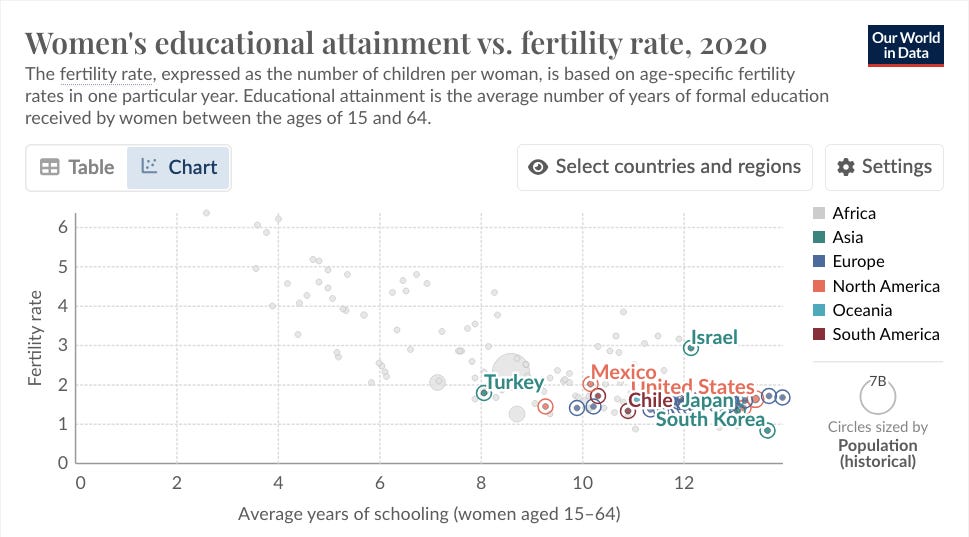

So yes, Israel has a much larger fertility than any other OECD nation. And what really interests people is often the way Israel’s fertility is above replacement even though it’s still relatively educated: even among secular Israeli women, the fertility rate was recently measured at 2.0, which is still somewhat above the average for OECD nations.1 On a country-wide scale, the national relationship between women’s average years of education vs. fertility ends up looking like this for countries in the OECD in 2020:

As you can tell by the greyed-out points on the graph, there’s an inverse relationship between women’s education and childbearing worldwide; but when you look only at the OECD, the relationship disappears, and Israel stands out as being more fertile than the others, while still reasonably well educated. Is there something special about Israel?

Is There Something Special About the OECD?

Wikipedia calls the OECD “a forum whose member countries describe themselves as committed to democracy and the market economy,” but the grouping is pretty loose; democratic Romania is still waiting for approval, while Mexico is all in, despite not being very democratic (the Economist Intelligence Unit now finds Mexico is better described as a hybrid regime than a democracy2).

So if we’re amazed about Israel’s fertility among OECD nations, the obvious rejoinder is to say that the OECD is just a loose collection of somewhat wealthy countries, in which Israel stands out for more reasons than just fertility: Israel also spends the largest percentage of its budget on defense,3 its economy experienced the biggest slowdown in 2024,4 and it scores as least peaceful on the Global Peace Index (GPI), a measure of societal safety, conflict, and militarization.5

Looking at issues like this, the obvious question is, “Why do the other OECD nations put up with an aggressive, high fertility middle-Eastern country among their ranks?” Consider for a moment the other country that’s been in the news lately for rattling her saber, Russia. The OECD did consider including the Russians for a while, but suspended talks in 2014 after Russia annexed Crimea,6 and excluded them completely in 2022 after their invasion of Ukraine.7 If international bellicosity is a problem for the OECD, maybe Israel won’t be a member for long? Israel isn’t nearly as wealthy as Russia, but then again it probably doesn’t hurt to have a powerful lobby in the United States.

In other words, what comparisons like this show is not that Israel is special, but rather that Israel is in strange company among the nations of the OECD. If you look at the same graph of women’s fertility vs. education for countries in the Middle East, a very different picture emerges:

Now we can see the inverse relationship between fertility and education showing up in the data—and if Israel is unque here, it’s in terms of how well educated Israeli women are, with 12 years of schooling on average compared to 10 years in Iran, 8 years in Turkey, and around 5 years in Yemen. Israel is also the wealthiest in the region, which shouldn’t come as a surprise given the overall poverty of the area and Israel’s historical and cultural ties to wealthier nations.

But What About Secular Israeli Women’s Fertility?

When we look at secular Jewish women in the United States having a total fertility rate of 1.08—half of the fertility rate of secular Jewish women in Israel—it may seem as though there just has to be something to explain. Commenters on Kryptogal’s Forbidden Closet of Mystery tell me things like, “We should just look at Israel and discover what they are doing, even educated secular women have a good fertility rate there. It is possible to have a fairly liberal society and somehow have women make a sufficient amount of baby,” and “l believe educated secular Israelis also have higher than expected rates, not as high as their compatriots but higher than their western counterparts.“ And while people who don’t understand sociology friendly and well-meaning folks around Substack may have a right to think there’s something special about Israel’s fertility rate, that doesn’t mean they are right to think there’s something special about Israel’s fertility rate. Because in fact there is a well known pattern for our relatives, neighbors, and colleagues to influence our own fertility:

Research has indicated that fertility spreads through social networks… [C]olleagues’ and siblings’ fertility have direct consequences for an individual’s fertility. Moreover, colleague effects are concentrated in female-female interactions, and women are more strongly influenced by their siblings, regardless of siblings’ gender.9

This is just one study from an enormous body of research covering social influences on fertility decisions. Although we have a natural tendency to assume that the demographic transition was an economic inevitability, a 2021 study, “Fertility and Modernity” finds that, as with many problems in recent history, you really can’t avoid blaming the French:

We investigate the determinants of the fertility decline in Europe from 1830 to 1970 using a newly constructed data set of linguistic distances between European regions. The decline resulted from the gradual diffusion of new fertility behaviour from French-speaking regions to the rest of Europe. Societies with higher education, lower infant mortality, higher urbanisation and higher population density had lower levels of fertility during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, the fertility decline took place earlier in communities that were culturally closer to the French, while the fertility transition spread only later to societies that were more distant from the frontier. This is consistent with a process of social influence, whereby societies that were culturally closer to the French faced lower barriers to learning new information and adopting novel attitudes regarding fertility control.10

Basically what all of this means is that it’s inappropriate to compare the fertility rates of secular Jewish women in America and secular Jewish women in Israel and say “there’s something special about Israel.” The conspicuous presence of the Haredim, who make up 13% of the population11 and average 6.1 children per woman12 has an impact on other Israeli women, whether in terms of their effect on social networks, in terms of legal and cultural norms, or even consciously, in terms Monica Toft wrote about in 2021 as wombfare:

Wombfare is the use of fertility as a political weapon to defeat rival ethnic and religious groups. The tactic is deployed by both religious and secular groups to support their long-term objectives of gaining political influence over competitors13

(For those of you who don’t spend your lives wandering through sociological journals, congratulations on your discovery that “wombfare” is a thing.)

Monica Toft’s article appears in A Research Agenda for Political Demography, which is a highly readable reference on population shifts and their importance for understanding the world we live in. Toft points out that groups like the Mormons in America, or Jews and Muslims in Israel and Palestine, have made conscious decisions to bear children because of their awareness of the demographic vulnerability of their own group.

I will say it’s hard to be sure how much of the difference between Secular American Jewish fertility and Secular Israeli Jewish fertility there even remains to explain after you consider the different social, economic, and cultural differences between the two countries. Cultural context can explain a lot, and the fertity gap between the two groups is only one one child per couple. But to the extent that we still feel as though we need an explanation for that gap, it isn’t hard to find one in the militaristic culture of Israel, combined with the fear of your country being crushed by hostile neighbors.

Unfortunately, this is a far cry from the idea that secular Israelis have discovered some fertility secret that we could all stand to learn. Those of my readers who are concerned about WEIRD people failing to make enough babies may have to look elsewhere for solutions to demographic collapse in the developed world.

In Conclusion

If Jewish women in Israel are having lots of kids, it’s pretty easy to explain in terms of:

The fact that Israel is a country in the Middle East where fertility rates are high,

The presence in Israel of large numbers of religious groups like the Haredim and the Bediun, and the influence they exert on the culture and social networks of the country, and,

Good old fashioned wombfare.

If you were genuinely wondering about educated secular women having anomalously high fertility, you might in fact take a look at women like Mrs. Apple Pie, and try to figure out what in the world a Godless woman born and raised in America with no siblings, no high-fertility friends or colleagues, and a degree in physics, is doing trying to have a seventh kid.

(Just don’t be too disappointed when part of the explanation is that she really, really likes her husband)

Reuters & TOI (2024). Israel’s birth rate remains highest in OECD by far, at 2.9 children per woman. Timesofisrael.com. https://www.timesofisrael.com/israels-birth-rate-remains-highest-in-oecd-by-far-at-2-9-children-per-woman/

Egelhoff, R. (2022, February 14). Mexico now a “hybrid regime,” having lost ground on Democracy Index. Mexico News Daily. https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/mexico-loses-ground-on-economist-democracy-index/

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. (2023). SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. Sipri.org. https://milex.sipri.org/sipri

Israel’s economy sees biggest slowdown among OECD countries as war drags on. (2024). Timesofisrael.com. https://www.timesofisrael.com/israels-economy-sees-biggest-slowdown-among-oecd-countries-as-war-drags-on/

Vision Of Humanity. (2024, November 27). Global Peace Index Map » The most & least peaceful countries. Vision of Humanity. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/#/

Welle, D. (2014, March 13). OECD suspends Russia accession. dw.com. https://www.dw.com/en/oecd-suspends-russia-accession-talks-while-moscow-vows-symmetrical-sanctions/a-17494773

Burns, T. (2022, March 9). OECD suspends Russia, Belarus from any participation. The Hill. https://thehill.com/policy/finance/597443-oecd-suspends-russia-belarus-from-any-participation/

Mitchell, T., & Mitchell, T. (2024, February 15). 10. Jewish demographics. Pew Research Center’s Religion & Public Life Project. https://www.pewresearch.org/religious-landscape-study/2021/05/11/jewish-demographics/

Buyukkececi, Z., Leopold, T., Van Gaalen, R., & Engelhardt, H. (2020). Family, firms, and fertility: A study of social interaction effects. Demography, 57, 243-266.

Spolaore, E., & Wacziarg, R. (2022). Fertility and modernity. The Economic Journal, 132(642), 796-833.

"Statistical Report on Ultra-Orthodox Society in Israel". en.idi.org.il (in Hebrew). 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

Toft, M. D. (2021). Wombfare: the weaponization of fertility. In A Research Agenda for Political Demography (pp. 101-114). Edward Elgar Publishing.

I agree with this, though I think it's much more (2) than (1) or (3), but it needs a little more explanation because Charedim are roughly the same proportion of Brooklyn as they are in Israel, and they don't boost fertility there. I made a post about this: https://nonzionism.com/p/why-is-israel-fertile

I totally support blaming the French. It is usually a good first guess, and often the second as well. Third is usually to blame a German. It seems like most of the really bad ideas that caught on since the 1700’s have come from one of those two regions.

On the cultural side, one could probably do a fair bit of moving towards larger families by making good films and television featuring people with bigger families being happy instead of focusing on the misery of too many kids or siblings. That’s a big ask because once propaganda is a goal quality suffers, but it does occur to me that in many movies growing up having a big family was a source of strife not happiness. You’d want people to see the bigger family and say “I want that.”