Human Societies Across The World

Prehistory as I understand it

I know some subjects very well—mathematics, psychology, physics. Then there are other things, like philosophy, that I don’t really know that well, but I know well enough to feel confident having opinions. (Usually my opinion is “no;” most philosophers don’t realize, or don’t care, that what they’re doing to philosophy is basically what Aristotle was doing to physics.)

But then there’s sociology, anthropology, and archaeology.

These are areas that I find fascinating, but my understanding is wobbly, particularly as discussion veers into the past. So what I’m about to do here is a little different from what I usually do. Usually I feel quite confident about what I want to say, and I just want readers to be able to share my understanding. But today I’m going to give you a blog post in the more traditional sense: a web log, letting you know where I am on a journey to understanding the scope and variety of human societies.

Compressing Information

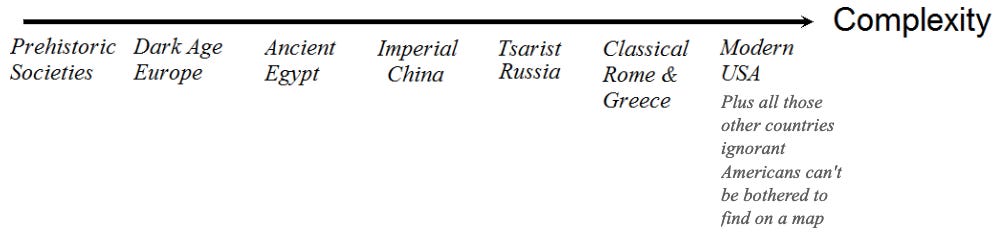

I’ve said before that understanding things means finding ways of compressing information. Here’s a start on how I personally do it with human societies:

Is this the best order? Maybe China should be further to the right, Greece and Rome further to the left? Is “complexity” even the best way to organize things, or the best term for what I’m getting at? I’m not sure—this is just where I am.

I do know the level of technological progress and economic specialization in human societies is very different across the world, and has been very different across history. In some societies, social groups are very small, and everyone does essentially the same thing: hunt or gather for food, make tools, raise children, care for the sick, sing, dance, build houses and clothes, throw pine cones at their elders, that sort of this. But in other societies, people have dramatically different functions, relating to the technology that has been developed. This is why I’m calling this dimension “complexity;” I think what matters is the way we keep moving to the right until each person serves one specific function in a huge, intricate society.

In addition to societies varying in complexity, we also find that values, beliefs, expectations, and behaviors are very different from one place or time to the next. Although there are many ways cultures differ, the strongest and most obvious difference is the level of individualism people value and expect in their daily lives.

What I find especially interesting is the way that societal complexity and individualism relate to one another. Ethnographic research suggests that freedom and equality drop lower and lower as societies become larger and more complex, until they reach a low point in large-scale agrarian societies, where the emperor is god on Earth and most everybody else is just lucky to be able to serve him. But this is the low point. After this, more complexity starts to turn things around. Modern surveys corroborate right-hand side of this curve: today, cultures value individualism and equality more as they become more complex.1

I’m not sure this curve is quite right; I have a sense that the right tip might actually rise above the high point on the left tip by now? But I’m fairly confident this relationship really exists, at least on the right half. I don’t want to bog the post down with technical arguments, but just look at, say, the work of Jean Twenge, and the numerous ways she documented rising Individualism in modern society: The increase in I/me vs we/us in language,2 rising rates of Narcissism3 and Extraversion,4 increased profanity use,5 delayed onset of adult responsibilities,6 ad nauseum.

There are more appealing sides to individualism, of course, like fairer treatment for women or child labor laws. But I’m not trying to give a thorough, unbalanced review here, because nobody I’ve met thinks society is becoming less individualistic—or less complex, either. Even if there’s no causal relationship between those complexity and individualism, Western society is becoming more complex, and also more individualistic, just as I sit here writing about it. And we have plenty of examples of poorer countries where, if we squint, people seem to be acting the way they did in European cultures hundreds of years ago.

Lets Have An Example

For instance, a Dutch social psychologist named Geert Hofstede collected a bunch of cultural data on different countries. Here’s a graph of the Individualism scores he found for three random Muslim majority nations, and one random Western nation (you can generate more graphs at that site; it’s fun to play around with):

Now Britannia is no longer the site of a thriving a medieval society. But it used to be, centuries ago. As Rosie Gilbert says on her lovely website:

Generally, during the bulk of the medieval period, a married woman would have covered her head with veils, wimples, cloths, barbettes, hairnets, veils, hats, hoods or a combination of them to avoid her hair showing.

And given the way Muslim nations are much less individualistic, maybe this photo is not much of a surprise:

So the cultural change going on at the right-hand of that graph above is not just well documented, it’s something you can see just by looking around. As societies develop, modernize, build wealth, and overall increase in complexity, something happens, and individualism increases as well.

Now this is the interesting part. Because what that something is, I’m not quite sure. But people have been noticing this change, and speculating about it since before I was even born. For instance, Ronald Inglehart says that something is material independence, and he may be right.7 Personally, I tend to think it’s more genuinely freedom of movement—if there’s a way to escape an oppressive boss, relative, or social situation, then people just will—but obviously when people become wealthy they naturally find it much easier to move away from controlling people or norms.

The left half of the Complexity Curve

But the left half is where things get really dicey for me. If Inglehart’s story were all there was to it, well, prehistoric peoples, and the few traditionalist societies we still have today, would basically consist be a bunch of conformists slaving away in rigid hierarchies. Right? Less wealth means less freedom and less equality.

But this doesn’t make any sense—hierarchy itself is complex. Say you’re a prehistoric woman; you can’t have much of a hierarchy when society consists of you, your besties, their husbands, a few kids, and your mesolithic toolkit. Fine, you can tell your kids who’s the boss all you like, but what do you think happens when you forbid your adolescent daughter from picking prehistoric fruit with that filthy boy who’s always throwing pine cones at you? She leaves! Why would she stay? It isn’t though you have a monopoly on grass skirts, baskets, and bone awls. She does the individualist thing and goes picking fruit without your permission, sorry.

(By the way, today the Internet told me prehistoric fruit looked like this; I can only guess what their apple pies tasted like. Be glad you live in the 21st century)

So as anthropologists tell me, life in the earliest social systems wasn’t merely superstitious and savage; it was also fluid and free—governments didn’t exist, authority was weak, and there was no distinction between rich or poor. Only as technology advanced could societies became more stratified, more static, and more collectivist. And then after: Only as societies became increasingly complex, and everyone was wealthy enough to move freely about once again, did they again live lives we recognize as individualistic.

At least, this is what anthropologists tell me. They rely on a lot of ethnographic data that I’ve never analyzed myself, but the claim by researchers like Pierre Van Den Berghe is that societies differ importantly in terms of the way humans have traced their kinship.8

Individualists like ourselves, and supposedly, like our foraging ancestors, didn’t need to organize themselves together much. But as societies developed a bit, group sizes increased, and it became extremely important to band together so that you could cooperate, if for no other reason than to fend off attacks from other cooperating bands. The result was the clan.

The Clan

Arranging people into clans made it very easy to band everyone together, as it was quite obvious who was on who’s team. But since relatedness can be a bit confusing, societies came up with two (well mainly two) different strategies for choosing teams. Say you’re a man this time, and consider the options:

Strategy 1: Matrilineal Descent. You are on your mother’s team with all of her relatives. If you’re of the male persuasion, you move in with your girlfriend’s family and help them out until you get bored or she kicks you out. No question about who is related to you here, and bonus: no hanging around with a girlfriend who hates you! OK so maybe the women don’t have it so great; mostly they do all the work gardening while you sit around until it’s time to hunt, or go on a raid. And maybe you have to hang around a mother-in-law you hate, but whatever; if she drives you crazy, brah, just leave! Solid system, the matriclan.

Strategy 2: Patrilineal Descent. You are on your father’s team with all of his relatives. At least, you think he’s your father. So you think you’re on the right team. But it’s before the age of paternity tests, and frankly he’s always been a little suspicious of you. Oh well, at least he helped arrange a marriage for you by bartering some of his cows, and your bride can’t run away, because your family tied her up after they grabbed her. No no, don’t worry, not literally! (Well maybe literally.) And it’s not like she isn’t totally into you! (Well maybe she isn’t at first, but just persevere; it worked with Genghis Khan.) Plus this way you can pass all of your cows on to your sons, and that’s a good thing!

It may seem strange that we’re talking about livestock all of a sudden, but livestock is actually extremely important. It’s one of the most ancient forms of transmissible wealth. We’re used to thinking about precious metals as money, but metal is rare, and you can’t eat it. Cows on the other hand directly support life, and unlike fruit or grain, they transport themselves.

The root of our own word for wealth, “fee,” seems to come from old Germanic. It’s been preserved in writing as the f-rune, fehu, from the very start of the first aett. You can’t miss the horns:

And the fact that livestock meant wealth to our ancestors gives rise to an old saying among anthropologists: The Cow is the Enemy of Matriliny. 9

The Cow is the Enemy of Matriliny

This is my understanding: Inheritance is the thing that differentiates between the matrilineal and patrilineal kinship patterns. If you live in a relatively low-tech society where wealth is more or less equal, everybody is hunting, gathering, fishing, or hoe-farming to get food, and there’s just no way to be confident who is really related to whom, then matriliny is the way to go.

But as people move out of the woods and society creeps to the right in complexity, wealth and status matter more and more, and well, who wouldn’t marry their daughter off to someone with plenty of cattle? She can’t run away anymore, because you’re either animal herders living in the desert, or hard-core agriculturalists who survive from all the technology you’ve developed. So she can’t just go traipsing about in the wild picking weird fruit. Your daughter is yours, and she’ll do as she’s told.

But what about your son? Why not sell your son to a woman with lots of cattle? It turns out this doesn’t really work. For one thing even though there’s some technology, it’s still a world of strength, where men tend to call the shots. And of course there’s the fact that women tend to have lower sex drives than men; so most women aren’t really going to pay money for your son.10

But most of all, underlying the patrilineal kinship system is a simple evolutionary principle, that reproductive success is more variable for men than women. What that principle entails is this: your daughter will likely just have the children she has. Keep her safe, keep her alive, there’s not that much you can do to change things for her. Your son, on the other hand, is another matter. He could have one wife, or two, or twelve, and go on to have a hundred children. Or he could have none at all. And what you do for him can influence this. Your ability to pass on your genes through your son depends on his advantages and disadvantages, like his confidence, or skill as a craftsman, or physical prowess, or all those cows he can inherit from you to buy wives—but only if he’s your son.

Fortunately that question of paternity certainty, that minor issue of making sure he really is your son, is easy, so long as you can completely oppress your wife. Better not take chances there; on the plus side your own parents have a genetic interest in helping you out with that. So now you know your son is really yours, and when you get him a wife of his own, their grandchildren will really be yours. And don’t worry; after his new wife has had a few children, she’ll realize he really is pretty great, not just some guy with a bunch of cattle, right?

So I Don’t Like Patrilineal Descent Systems

They’re definitely interesting. But ultimately, I think patrilineal societies are mean, and encourage humans to develop in strange ways that I’ll talk more about another time. [Edit: See here.] And given the importance of inherited wealth for patrilineality, I don’t really care for herding as a means of subsistence, either. But advanced, plough-agriculture is even worse; the impression I have is that those sprawling agricultural societies exist at the very bottom of the complexity-freedom curve.

In other words, under an early herding society you have a bunch of oppressed women, while under an advanced agrarian civilization you have a bunch of oppressed everybody.

Were people really as bad off in those societies as they seem? Maybe this is just a bias I picked up from reading too many anthropologists in college? I’m not sure. (There’s a lot I still don’t know. If you have any information about this, let me know in the comments!)

But old school, primitive agriculture, before people hooked up a big metal plow to their oxen, and everybody just hoed the earth using sticks? That seems not too bad. And given the absolutely enormous amount of time humans spent wandering around living in low levels of cultural complexity, these kinds of societies probably lasted for a long, long while. Just take my advice, people: if you must have clans, pass your lines of descent through the mother. And if you really want to invest in a male relative, hey—there’s always your favorite nephew!

Hofstede, G. (1984). Culture's consequences: International differences in work-related values. sage.

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, W. K., & Gentile, B. (2013). Changes in pronoun use in American books and the rise of individualism, 1960-2008. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 44(3), 406-415.

Twenge, J. M., Konrath, S., Foster, J. D., Keith Campbell, W., & Bushman, B. J. (2008). Egos inflating over time: A cross‐temporal meta‐analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of personality, 76(4), 875-902.

Twenge, J. M. (2001). Birth cohort changes in extraversion: A cross-temporal meta-analysis, 1966–1993. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(5), 735-748.

Twenge, J. M., VanLandingham, H., & Keith Campbell, W. (2017). The seven words you can never say on television: Increases in the use of swear words in American books, 1950-2008. Sage Open, 7(3), 2158244017723689.

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Cultural individualism is linked to later onset of adult-role responsibilities across time and regions. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(4), 673-682.

Inglehart, R. (1971). The silent revolution in Europe: Intergenerational change in post-industrial societies. American political science review, 65(4), 991-1017.

Van den Berghe, P. L. (1990). Human family systems: An evolutionary view. Waveland PressInc.

Aberle, D. F. (1961). Matrilineal descent in cross-cultural comparison. In: D. Schneider, & K. Gough (Eds.), Matrilineal kinship ( pp. 655 – 730). Berkeley: University of California Press.

How things worked for people we would regard today as homosexual, asexual, intersex, or other is something I’m interested in, but frankly don’t know much about.

1. Have you read Peter Turchin? He, like some others, insists that history really is going in a certain direction all the time. According to Turchin, history is a dialectic between civil war and war against outsiders. There is a process of evolution going on in favor of the larger-scale units.

The middle ages might have looked rather much like any horticultural small-scale society. But under the surface, important steps toward higher levels of internal cohesion were taken: Christianity was tearing down clan structures. Broad social cohesion was being built through a religion celebrating a victim.

2. When it comes to patrilineality and matrilineality, I need data before I believe anything at all. Unfortunately I don't have that data. I recently read about two primitive societies: The Dani of Papua New Guinea and the Tiwi of Australia. The Dani are patrilineal and were in a constant state of war with their neighbors. I have only read one book yet and it only said that husbands could be violently jealous.

The Tiwi were are matrilineal hunter-gatherers, pacified since decades when the study I read was made in the 1950s. All Tiwi females were always married. A man who wanted to marry needed to recruit a mother in law. Then he needed to support her and he would hopefully get the daughter or daughters she would give birth to as wives. The mother in law was mostly younger than the son in law. This meant that girls of about ten years were given away to men who were most often about forty years old. The Tiwi believed menstruation was caused by sexual activity, so marital sexual activity began early. When those girls reached their late teens, they often found out that young men were more attractive than their old husbands. The husbands could use older wives to spy on their younger wives. Infidelity frequently lead to duels were the legal husband was given a huge advantage.

I also read about the Canela, a formerly very war-like Amazonian people. The Canela were matrilineal. On the one hand, they were promiscuous. Recently married teenage girls were forced to have group sex with a number of men. If they refused, they were raped. When a couple had children together, they couldn't separate until the children had grown up.

And at last, the famous Yanomamö. The Yanomamö were patrilineal. They were horticulturalists. Men were very jealous and violent in order to keep their wives from having affairs. Women had very little say regarding whom to marry.

From the information I have, I see little pattern at all. The two matrilineal societies I mentioned were mostly hunter-gatherers and the two patrilineal societies were horticulturalists. But all were technologically primitive and owned little. One, the Dani, owned pigs, but the Yanomamö abhorred the thought of killing domestic animals. Still, they were patriarchal, jealous, cruel and polygynous husbands.

I'm hoping for some better data to show up, because as things are I can't see any clear patterns except that poorer and less advanced societies tend to be more matrilineal. I can't even see that men in matrilineal societies would be less jealous: Paternity certainty is always a good thing for a man, also when there is nothing to inherit. Men have always tried to get as much sexual exclusivity as possible. In very hazardous environments, sharing a child with another man might have paid off. Men have also shared women for reasons of bonding and equality. But as soon as men think they can afford it, they like to monopolize women.