As a teenager I was accused of having an obsession for Medieval Europe. Though it rankled at the time, it was a fair assessment, given that I hadn’t yet discovered Ancient Egypt, Classical Greece, or Imperial China. See it turns out that I’d been raised and educated by American Baby Boomers:

Unfortunately I have no idea what anyone else’s excuse is, because they all continue to treat chess as though chess is The Game Smart People Play. While most chess enthusiasts may not be eager to disabuse people of the notion, many do suspect that the persistent belief in chess as a measure of human intellect is probably exaggerated. For instance, the openings to chess have been catalogued and explored many moves in, and this is something that can simply be learned, requiring only patience and interest in the game, not talent.1

And modern meta analyses support this conclusion: Although chess is a fair predictor of mental ability for children, where it shows correlates around r = 0.3, considering adult samples or groups of ranked players reveals correlations closer to r = 0.1.2 Meanwhile, while I don’t have a meta analysis on the importance of practice, a longitudinal study on the effects of practice on chess skill reports r = 0.79 between ELO rating and hours of individual practice, and r = 0.94 for group practice.3 Yes, fine, the sample size in this last study was only n = 104 players, but correlations of this magnitude don’t fall from the sky.

But pointing this out to people doesn’t change the essential nature of Western civilization, which reveres chess skill as one of the highest examples of human intellect. This is such a deeply-ingrained notion that the fate of supercomputers thousands of years in the future still depends not on their ability to calculate trajectories at relativistic speeds, or figure out how to maximize the number of paper clips they can make in an hour, but play chess:

Sure, chess involves more memorization than creativity, just like Bobby Fisher said. Sure, after you obtain a material advantage chess often descends into attempts to bore your opponent into making a blunder. But many, many people worth getting to know and talk to absolutely adore the game, so I sighed, shook my head, and played enough chess to get reasonably good at it—good enough that I eventually made $50 an hour tutoring people in chess. The social aspect still made it worthwhile, and frankly it’s hard to complain about chess being a poor marker for intelligence when people are paying you to be a good player.

Yet while everyone might be excused for thinking chess is a game for towering geniuses, no one who’s even spent an hour playing the game can say it’s never occured to them that kights hop around like frogs, castles walk surprisingly fast for bits of architecture, and the queen has a jetpack shoved up her butt. The official name of the version of chess everyone plays across the Western world today is Mad Queen Chess, and no unlike Dave Barry, I am not making this up.

There’s a reason chess looks like it does today, though, and that reason is because when chess first reached Christendom, it seriously wasn’t any fun to play. The original rules, taken from the Persian game of Shatranj, a very close descendant of Indian Chatturanga, are well known.

Pawns: These moved forward one space only, not two at the start

Alfin (elephant, not bishop): These jumped exactly two spaces

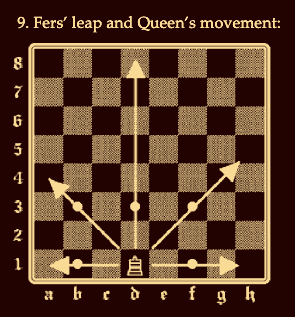

Ferz (not a queen): This piece moved one space diagonally. That’s it.

Victory: Achieved through checkmate, or by killing all pieces besides the king.

Castling: You have got to be joking

Although the names for some of the other pieces change, such as the rook being a chariot in Chaturanga, everything else was the same. If you try it for yourself, you’ll see that the game does feel more plausible with the way the pieces move, but it was also deadly dull, taking five or six moves before the pieces are even able to threaten one another.

In his lovely article “How did the Queen Go Mad,” Mark Taylor4 points out that Medievals improved the speed of the game by adding leaps around the 13th century, which I can verify allowed not only the pawns but also the king and the queen to jump two spaces for their very first move. (Different regions used slightly different leaps, and St. Thomas Guild has a lovely article if you’re interested.) Some time after these leaps appeared, castling was introduced as another leap, and then the alfin and ferz were replaced with new pieces we know named bishop and queen.

Long and detailed arguments are made that this first took place in the 15th century under the reign of Isabella of Spain,5 but I am rather inclined to agree with Taylor when he quotes autier de Coinci’s Miracles de la Sainte Vierge, a treatise dating back to the start of the 13th century, which translates thus:

Other ferses move but one square, but this one invades so quickly and sharply that before the devil has taken any of hers, she has him so tied up and so worried that he doesn’t know where he should move. This fers mates him in straight lines; this fers mates him at an angle; this fers takes away his bad-mouthing; this fers takes away his prey; this fers always torments him; this fers always goads him; this fers drives him out from square to square by superior strength.6

I read that and easily recognize a modern chess queen being used in some variants from a very early point. Whether you reach the same conclusion or not, experimentation was clearly going on for quite some time, and by the 16th century the popular French variant was literally called “echés de la dame enragée.”7 (Because hey, what’s more fun than a crazy French lady?)

Let me clear in saying that I don’t object to any of these improvements. They did make the pieces move strangely, in a way that makes it very hard to take seriously the idea that they represent an actual battle anymore, but the game is much more enjoyable as a result. However, I definitely object to the way these innovations ground to a halt. From a historical standpoint, this is somewhat odd. In fact, there’s a case to be made that we’ve been playing chess for over five centuries the non-traditional way, because traditionally, chess was always in flux, played differently in different places and different times. When the Renaissance ended, across the entire Western world, chess became frozen in amber.

Now maybe this would make sense if chess had reached the apex of its possible development in the 16th century. After all, when something gets really, really good, why make more changes? Don’t fix what’s broken, right? But the fact that the silly ways in which the pieces move prevents it from being taken seriously should give conservative chess enthusiasts some cause for disquiet. I get that Elizabeth Harmon scored points against a pushy interviewer by calling chess “just pieces,” but ultimately that kind of retreat into literalism is inevitable with the game that’s divorced from the realm of plausibility. Wouldn’t a window into a genuine life-or-death struggle between evenly matched forces be better than an abstract competition between wooden figures on a board?

But whatever, say we don’t care how ridiculous the mad queen is. Even if chess is “just a game,” it isn’t hard to point out engaging features of strategy games that chess is missing. For example, consider Westwood’s Command & Conquer, which gives players the ability to harvest and sell tiberium to build walls, structures, and armies to move around the board in real time, fighting under conditions of imperfect knowledge known as fog of war. These features speak to the critical importance of supply, finance, rapid response, and intel in actual warfare.

Now chess does have some of these features, at least to a point. You can build up your position in the begin game by developing knights, fianchettoing bishops, and eventually castling your king; more literally your army can be strengthened by promoting a pawn at the back rank. And of course a sense of real time urgency can be gained by using chess clocks.

But what about fog of war?

While that may not seem possible in a board game without dice, cards, or a clunky system of writing secret moves on a sheet of paper, there are simple and elegant ways of adding fog of war to a non-computer game like chess that have been in use for decades, if not centuries. So, how might they be used to make chess a better game?

Chess in the East

I’d like to broaden the frame for a moment.

We’ve been looking at chess in the West for the past fifteen hundred words, but even though chess is neither a Western invention nor a game unique to the West, I’m willing to bet that it never occured to most of my chess-playing readers how fixated they’ve been on Western chess. OK so maybe you learned chess from American Boomers, which is understandable; after all, that’s how I learned it.

Asian chess, in contrast to chess in the West, was influenced by Go as it reached China to become Xiangqi, where pieces occupy intersections and fight across a river:

As Xianqi is directly descended from Chatturanga, it has many similarities, with a recognizable ferz, chariot, alfin, and knight, though the latter pieces aren’t allowed to jump, and other pieces are quite different. For instance, unlike pawns, soldiers attack forward rather than diagonally and may move and attack horizontally after crossing the river, while the generals are restricted to their palaces except in the event that they can see another general along a file, in which case they literally execute a “flying General move” to kill their opponent. (No I am not making that up either.)

Though I had friends growing up who loved Japanese Shogi, a further descenant of Xianqi, I’ve played these games a few times, and this is not a lineage that particularly interests me. What I am most interested in comes from changes made to the game in a third branch to emerge from Chaturanga as it made its way south. We’ve seen the branches to the left and right; what about the middle branch?

Chess in the Southeast

When Chaturanga reached Thailand, they realized the same thing that Western players did: The start of the game was too slow. But rather than solving the problem with initial leaping moves, they simply pushed the pawns forward, to make their own local game called Makruk:

There are some other little differences from the original; for example, the bishop or elephant in Makruk moves one space diagonally or directly forward, a movement pattern shared with the silver generals of Shogi. But for the most part, Makruk is really a limited improvement over Chaturanga, and I wouldn’t recommend playing it.

However I do think we’re lucky this variant survives, because it serves as a missing link between chess as played in India, and chess in Burma, known as Sittuyin:

As you can see, in Sittuyin we have a serious answer to the languid gameplay of Chaturanga as it began in India, pushing the pawns so far forward that they’re already able to attack one another, creating a tense position before the game even begins. The colors are red and black rather than white and black, and the pieces move as they do in Makruk.

The obvious next question of course is, “Where do the other pieces start?” And the answer is that depends on the whom you ask. The game was known to vary sigificantly across Burma, and while some sources claim pieces can go anywhere behind the lines, and pawns can even be swapped out with other pieces, the usual rules restrict chariots (or rooks) to the back rank, and the other pieces can only be placed between the back rank and the pawns.8 So for example, playing with a regular chess set, an opening setup might turn out like this:

As for the exact rules governing the process of placing pieces, sources variously indicate that players either take turns placing their other pieces behind their lines one at a time,9 or all at once,1011 or most sigificantly in secret, behind a curtain stretched across the board.12 Some sources claim this secret deployment method is the way the game is played in tournaments, while friendly games use open setups,13 but you can probably tell I really don’t care what anyone else says or does, because this way of shielding the disposition of your army behind a screen is the clear and obvious innovation allowing fog of war in a game of chess.

This is a variant I’ve played many times, and I can verify that it moves quickly, with a steady tension that only deflates if the rooks are traded. In Makruk, the elephants aren’t very useful, because they start so far back that many moves must be invested in them to bring them into play, but Sittuyin reveals them to be surprisingly powerful because of how well they integrate with pawn structures; elephants are significantly better at this than chess bishops, because they can move forward with a line. (Also it’s not hard to imagine having a freaking elephant backing you up would be a pretty good boost to morale.) Although Pychess doesn’t allow hidden placement, it does have a variant of Sittuyin using alternating piece placement you can play with AI.

Overall it’s quite a charming game, not least of all because of its cultural elements. When chess first reached Burma it was immediately viewed in religious terms as a retelling of the mythical Ramayana: After the ten-headed demon Da Tha Gi Ri abducts Rama's beautiful wife, Sita, King Rama and his ally Hanuman the Monkey King must defeat the demon’s army and rescue Sita; and while the game can be played merely as a military skirmish, the oldest Sittuyin sets reflect this mythic story.14

So Sittuyin has a lot going for it: Fog of war, realistic piece movement and strength, a cute background story, and enough variation at the start that it’s not possible to reduce the begin-game to a series of well known openings. But given the title of this article, the question we really need to ask is, is it better than chess?

And the answer is not really. After a while playing Sittuyin, it’s hard not to miss the pins, skewers, and pacing of Western chess in the middle and endgame. The rooks do come into play rapidly to allow for some motion across the board, but it’s all along orthogonal lines, and the knights don’t move far enough to connect the corners the way the bishops and queen do in chess. And while chess players know that feeling of mounting tension as a pawn approaches the opposite edge, the promotion rules of Sittuyin are complex and heavily restrcted, and the only piece you’re even allowed to promote to is the ferz, whom Mrs. Pie refers to scornfully as “a little peasant.”

So then why have I been writing so much about Sittuyin?

I suspect that Chess has stopped evolving not because people refuse to innovate (which is the cynical explanation) nor because chess is the best it can be (which is the impression chess officianados will give you). Rather, I think chess has reached a local maximum. It’s like a species which would need multiple simultaneous changes to gain any improvement, and evolution really doesn’t work that way—but neither does human creativity (usually). Trying to fix chess is hard, and it’s not for lack of trying.

A Thousand and One Knights

In 1994, D. B. Pritchard made an extensive attempt to catalogue everyone’s efforts to improve on the game with his Encyclopedia of Chess Variants.15 Pritchard’s work is absolutely amazing for its time, listing about a thousand16 variants, including:

ALICE CHESS: Played on two boards, one full and the other blank; after completing a move on either board, a piece goes “through the looking glass” to the opposite board.

APOCALYPSE: Played on a 5x5 board with 5 pawns and 2 Knights to a side. Moves are made in secret and occur simultaneously; if two pieces move to the same square, knights capture pawns, and otherwise both pieces kill one another.

BEAR CHESS: Played on a 10x10 board to make room for two bears! (RAWR)

BOMBALOT: With tanks! And detonators! And also bombs!

ENCHANTMENT: “Tony Berard (1988) Board 76 chequered triangles; 12 pieces and 8 pawns a side. The pieces are an odd assortment: Emperor (K), Mother Nature (Q), Death (R), Aphrodite (B), Mars (N) and two unique pieces, Time and Fate. A novelty is that pawns are either male (serf) or female (damsel) with

pleasing promotion logic (e.g., serf cannot become Mother Nature).”

FOOTBALL CHESS: “predictably there is a ball”

GAME OF THE FOUR SEASONS: A four-player variant played in the 13th century with rules like Chaturanga, and each player represents a season, an element, and one of the four humours:

KNIGHTMATE: “The royal piece is a knight and there are two non-royal kings. The object is to checkmate the knight.”

PROGRESSIVE CHESS: Every turn the player takes one more move than his opponent did on the previous turn, so 1, then 2, then 3 moves, etc.

QUEST CHESS: Players move ten different pieces a turn, but the opponent may interrupt to take back a piece in response to a capture.

REFUSAL CHESS: For each move a player makes, the opponent may refuse to allow that move, but must then accept the alternative.

SPHERICAL CHESS: The two boards represent connected hemispheres:

ULTIMA: An unusual variant in which pieces move as queens, but attack differently, with names like “immobilizer,” “coordinator,” and “withdrawer.” Though I find the dry, literal setting uninspiring, the gameplay of ultima may successfully diverge from chess, and there are further variants like ROCOCO that give at least a whimsical attempt as a setting.

WATERGATE CHESS I: “Each player keeps two scores. The move from

the first score-sheet is played on the board: however, up to 50% plus 1 moves may be… ‘inoperative’. Two moves later you reveal the move you actually made (recorded on the second score-sheet) and the board is revised. If [a] move turns out to be illegal, the turn is lost.”

WATERGATE CHESS II: “The inventor refuses to release details of this game on the grounds of executive privilege and national security. Moves on a scoresheet have been found erased.”

I could go on, but I hope the above gives a sense of the way people really have been trying very hard to improve chess over the years. Though we see some exceptions like Apocalypse, there is a clear tendency to “improve” the game by making either the playing field bigger, the pieces stronger, or the players’ options greater.

In his introduction, Pritchard invites the reader to consider this maxim: “that alteration (to chess) may be considered the worst that recedes farthest from it.”17 And I think these variants show this is correct, at least to a point: in order to make chess better, we’d have to change it so much that we might not immediately recognize it as chess anymore. While we might argue about the merits of conservative variants like Chess960 (towards which I admit a certain fondness) or Bughouse (which is terrible) I think everyone has really found a local maximum with chess. Simple variants to chess offer little and generally detract from the game, but more ambitious variants often make so many changes that one misstep ruins the outcome. Chess has reached its end.

But what about Sittuyin? This is not a game that’s been finalized. The rules have always been in flux. And if comparing it to chess reveals that chess has features Sittuyin lacks, then why not simply import those features into Sittuyin?

Specifically, if the main problems with Sittuyin are:

Not enough pieces have long distance moves, so that when one or both rooks perish, the game slows considerably,

No pieces run along diagonals to allow for pins, skewers, or forks in those lines,

The promotion system is complex and over-restrictive, and

The ferz is a grubby little peasant,

Then isn’t all of this very, very easy to solve? Just take some obvious inspiration from Western games, replace the ferz with a bishop, import the promotion rules from modern chess, give it a little nip and tuck, and we’ve got a sleek new variant of Sittuyin that may well be better than chess:

Assassin Situyin

Here’s how you play.

Using a regular chess set, arrange the pawns as shown:

Set up a curtain or screen between the player’s pawns. In secret, both players position the remainder of their pieces according to the following rules:

Chariots (or rooks) are placed anywhere in the back rank, with the king anywhere in between them.

Other pieces are placed anywhere in the next two ranks, behind the pawns. One and only one of these pieces may, at the player’s option, displace a single pawn, so that the pawn is placed amongst the other minor pieces.

Remove the curtain; red goes first, and pieces move as follows.

Pawns: They move forward one space without capturing, and capture one diagonal forward. If a pawn reaches the far side of the board, he immediately promotes to a knight, elephant, rook, or assassin at his controller’s choice.

Elephants: Replacing both bishops, elephants move one space diagonally or directly forward. (Four legs and a trunk, these elephants have.)

Knights: Jump in the classic L-shape, two spaces in one direction orthogonally and one to either side.

Chariots: Move any number of pieces in a straight line, like modern rooks.

Assassin: Replacing the queen, the assassin moves any number of pieces in a diagonal line, like a modern bishop. The assassin does not give check, and may take the king like any other piece to win the game.

King: Just like a chess king, he moves one space in any direction.

Victory: Achieved through checkmate, assassination of the king, by killing all pieces besides the enemy king, or by leaving your opponent with no legal moves.

Draw: Achieved if the same position arises three times, or if both players agree, but not via stalemate.

The Apple Pie family has played this many times by now. Pushing the king into the back rank gives a good castling-like option to develop by moving him forward to connect the rooks chariots. The rule allowing a single switch of a pawn and minor piece at the setup creates a definite feeling of excitement as the screen comes up and you immediately check for vulnerabilities or opportunities. Pawns rarely reach the back rank to promote, but gaining an additional chariot is decisive. And the assassin is absolutely perfect. While it’s really not an S-tier boardgame, and it may well need some additional tinkering, the Apple Pie family all agree that this variant of Sittuyin is, hands down, better than chess.

As a final note, while all of the above may make it seem as though this was a long chain of purposeful reasoning that slowly gave rise to Assassin Sittuyin, the reality was different: Many years playing chess, followed by the discovery of the one variant of Sittuyin that had pieces placed behind a curtain, followed by a few games, and then right away the obvious change from the ferz to a bishop, followed by a few more games and finalization of the rules, then followed by weeks of talking and research that went into this article. It’s extremely easy to think up a variant of chess and justify it with reasons why it’s bound to be good, but much harder to be confident of how fun it really is without playing it. In a sense, this entire article is meaningful only insofar as it can convince you this variant is really worth a try.

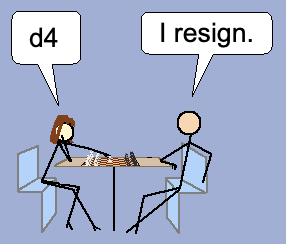

I like king pawn and English openings, but queen pawn openings are just unfairly strong. Sure, on the surface that may not seem to be the case, and computer analysis doesn’t reveal anything particularly amazing about a closed position, but once you understand chess is a game of interest more than talent it becomes obvious why there’s no way to win closed games: they bog down so rapidly, only a chess fanatic thinks its worth playing them. If your opponent leads with that queen pawn, they clearly like chess way, way more than you do, and there’s only one appropriate response.

Burgoyne, A. P., Sala, G., Gobet, F., Macnamara, B. N., Campitelli, G., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2016). The relationship between cognitive ability and chess skill: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Intelligence, 59, 72-83.

Campitelli, G., & Gobet, F. (2008). The role of practice in chess: A longitudinal study. Learning and individual differences, 18(4), 446-458.

Taylor, M. N. (2012). How did the Queen Go Mad? In O'Sullivan, D. E. (Ed.). Chess in the Middle Ages and early modern age: A fundamental thought paradigm of the premodern world (Vol. 10). Walter de Gruyter.

de Blanca, A. D. E. H., & Spain, V. D. R. M. The Birth of a new Bishop in Chess.

Taylor, M. N. (2012). How did the Queen Go Mad? In O'Sullivan, D. E. (Ed.). Chess in the Middle Ages and early modern age: A fundamental thought paradigm of the premodern world (Vol. 10). Walter de Gruyter.

Ibid.

Pritchard, D. B. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants. Games & Puzzles Publications. pp. 31–34.

Gollon, J. (1974). Chess Variants: Ancient, Regional, and Modern. Tuttle Publishing

Sittuyin | Cyningstan. (n.d.). http://www.cyningstan.com/game/234/sittuyin

Pritchard, D. B. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants. Games & Puzzles Publications. pp. 31–34.

Sittuyin from the Foothills of Burma. (n.d.). Chessorb.com. http://www.chessorb.com/sittuyin.html

PyChess. (2023, March 30). Sittuyin (Burmese Chess) - How to play. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WujZgsAWoFM

Nicolaus, P. (2002). “Myanma Sit Tu Yin.” Burmese Traditional Chess. http://www.chessvariants.org/oriental.dir/burmesechess.html

Pritchard, D. B. (1994). The encyclopedia of chess variants. Games & Puzzles Publications.

No I didn’t count them, but given that there are around 400 pages, many with five or more variants listed, it’s a reasonable guess. And if you don’t have time for shoddy guesswork, OK, these people confidently insist Pritchard’s book includes 19400 variants, and the Internet never lies

Pritchard, D. B. (1994). The encyclopedia of chess variants. Games & Puzzles Publications.

I think it's also a matter of Chess performing it's elite signalling function over it's fun generating function in its local maximum. That also happens to correlate with mental stimulation in this case, but anecdotally as an Australian Chinese child I introduced Chinese Chess to my primary school mostly for fun purposes as children are wont and it spread like wildfire in our corner of the playground until it was promptly banned for inflaming passions too highly. Xiangqi has been viewed, and probably selected, as a pastime rather than an exercise both mechanically and culturally I think. The stereotype of players in China is old men who would otherwise be playing cards. Whilst it's a similar demographic to older men playing Chess, I think there's a status difference in that these old men are more factory workers and uh, proletarians than old hustlers or bygone products of a more sophisticated age. They are otherwise gamblers. They do in fact gamble on Chinese chess.

This is probably because the elite signalling and intellectual exercise niche was filled by Go, which is also extremely abstracted and cannot really seem to be 'improved', having been abstracted into heat death.

Nice article; I was not aware of the SE Asian variants of chess.

Have you tried playing go? I would be interested in hearing your thoughts on that game