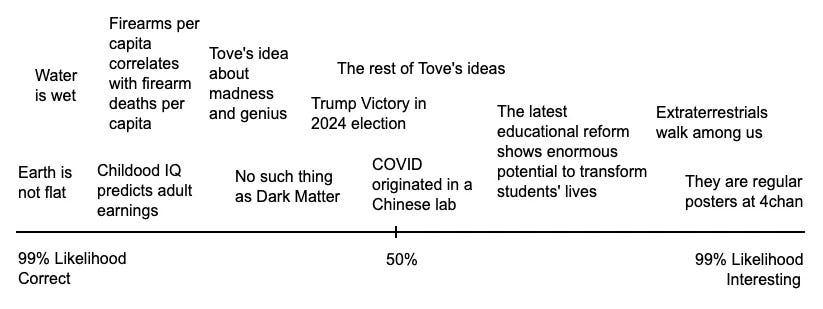

When Wood from Eden was in its infancy, I often responded to Tove’s claims with a percentage to rate how correct she was:

Granted, all this was mostly nonsense that Tove just played along with. However it did imply a tradeoff between how interesting an idea is and how plausible it is:

This scale is probably hovering around a point near the first third of itself, but never mind that; for the moment let’s just take it as being a thing. Thinking about it, it seems that most people’s ordering of ideas on this correct vs. interesting scale differs from everyone elses’ ordering, which implies that everybody has a chance to be a fascinating blogger. Just have a look at the ideas from the left-hand side of your own scale. Then write a post on one of them, giving all your reasons why it’s true. Chances are, everyone else ranks your idea further to the right than you do because they don’t know all of your reasons, and thus, they think you’re interesting—though probably slightly crazy, unless your reasons can convince them you’re not.

For example, consider the subject of dark matter. I don’t have to make it a focus of the entire post to point out a report or two that you may not have read. For example, here’s one from 2016:

For something that's hypothesised to make up more than 80 percent of the mass of the entire Universe, it's no easy thing to detect the existence of dark matter.

That's the conclusion the world is coming to today, after scientists announced that a massive $10 million experiment to find traces of elusive dark matter particles had failed after an exhaustive 20-month search.

And then the latest from 2024:

New research from the LUX-ZEPLIN detector in the US has found no evidence of dark matter.

The detector, which is the most sensitive in the world, is one of many around the world unable to find the elusive matter.

What does this mean for dark matter? Well, nothing necessarily. Just because you fail to find something doesn’t mean that something isn’t there. There is an alternative model most people haven’t heard about, called MOND, which explains the observed divergence from classical predictions in terms of a modified gravitational framework, rather than in terms of invisible undetectable non-baryonic matter which supposedly makes up around 80% of the matter in the universe.

Even though the question of dark matter is hardly settled, as a side effect of reading this post, you can suddenly be more interesting too by asking people “Have you heard? They still can’t find this dark matter stuff; I’m not so sure it exists.” A word of advice, though: Do have one of those links handy to avoid appearing crazy—in my experience most nonphysicists put dark matter exists near water is wet, and being crazy is pretty much bad.

Except that Tove Says Being Crazy isn’t All Bad

So a common theme at Wood From Eden is that mental disorders aren’t as straightforwardly negative as most people think. Tove has written this pretty directly in posts like Madness is Adaptive, and also in the comments section of Why Autism Exists, where she’s mentioned reviews like the 2018 “Creativity and Psychopathology,”1 which concludes:

The mad genius debate is a polarizing and divisive issue in the field of creativity research but with the neuroscientific, psychometric, psychiatric, and historiometric evidence reviewed here, it is likely that psychopathology and creativity are closely related; sharing many traits and antecedents but outright psychopathology may be negatively associated with creativity. Therefore, persons with full-blown schizophrenia or alcohol dependence may not be creative but only milder forms of all illnesses may be conducive to creativity. Family members of psychiatric patients may display higher levels of creativity, findings that are consistent in studies across all psychiatric disorders.2

These arguments are in fact quite old. The idea that delusions, hallucinations, or other classic symptoms of psychosis relate to creativity goes all the way back to classic philosophers like Aristotle, who famously opined, “no great genius has ever existed without a strain of madness.“3

Probably the researcher who best popularized the idea of a link between madness and creativity was Hans Eysenck,4 one of the giants of 20th century psychology. Eysenck held that vulnerability to psychosis is a fundamental ingredient in creativity.5 While I’ve always been a fan of Eysenck, his work in this vein was carried out using a scale he called Psychoticism, which measures a hodgepodge of traits like impulsivity, cruelty, and having a poor sense of taste (as in “Yes or no: Do most things taste the same?”), none of which have an obvious relationship to psychosis, relate well to one another, or even cluster together at a genetic level.6 A meta analysis checking whether actual psychosis is predicted by scores on Psychoticism did find a relationship, but its small size (r = 0.2) led to the conclusion that psychosis-proneness is simply not well measured by Eysenck’s scales.7

There was always more to the argument than this, of course; Eysenck noted that the relatives of emminent geniuses often had a psychiatric diagnosis.8 Even 21st century research finds that, while people with all-out schizophrenia or bipolar disorder don’t get very far creatively, their relatives have higher rates of artistic creativity than would be expected by chance.9

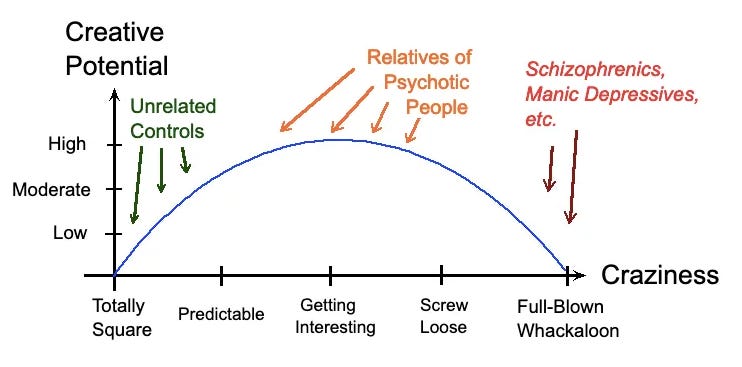

And this is at least somewhat convincing, isn’t it? If I’m completely nuts, then it stands to reason that my relatives are probably a bit weird. And if those relatives have higher than average creativity, then, OK, one interpretation is that madness relates to creativity like this:

Unfortunately for this line of argument, research also finds elevated rates of mental illness among (wait for it) the relatives of successful academics.10 This kind of finding prompts some hesitation.

Take a moment to think of everything you know about academia and the people who make it up. When I do that, I come up with a picture of conformity, not creativity. OK, yes, we might argue that successful academics do have some kind of creativity, of the muted sort that bloggers or journalists display in their work. But are the ranks of tenured professors who fill the halls of our local universities really creative in anything along the same lines as artists, or musicians, or video game designers, or people like Thomas Happ, who combined all three roles to produce Axiom Verge?

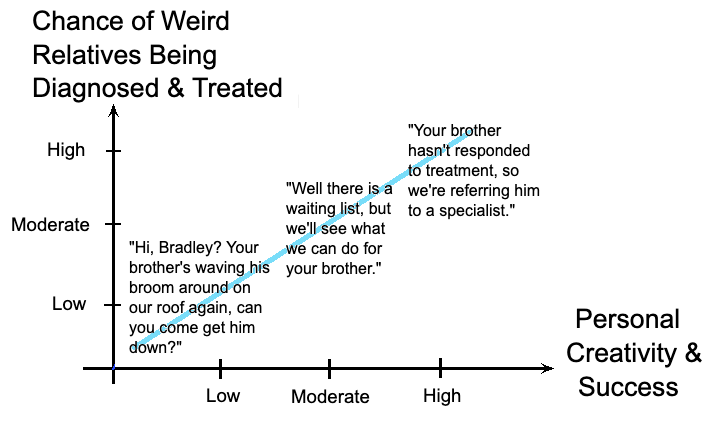

So the relatives of some people are more likely to be found to have a mental illness than the relatives of some other people. Such findings always raised the question of whether the kind of person whose mentally ill relatives have an official diagnosis, or receive psychiatric care, might really just be different from the kind of person whose relatives wander around harassing people in the middle of the night about being under surveillance by the CIA. The phenomenon of different kinds of people getting treatment for mental disorders at different rates has been touched on in other contexts, as conservatives avoid seeking treatment for mental health problems—they don’t feel like hanging around a therapist who’s opposed to their values. This isn’t just true for conservatives. It’s also an issue simply for everyone who’s poor, if we can trust surveys finding the most common reason Americans don’t receive care is because of the cost.

In other words, maybe what’s really going on is this:

To put it more directly, it’s no surprise that, if you won the Nobel Prize for curing cancer, your aging grandmother got a new kidney, your dyslexic brother got a tutor to help him read, and your autistic vegan transgender cat also received the diagnosis and treatment zhe had been needing. Successful people and their relatives are often helped out when things go wrong for them; maybe that’s all that’s being revealed by these studies.

Then Why Do Mental Disorders Exist?

One reason to think psychoses, along with more minor conditions like anorexia or autism, have an up side is the fact that they are

heritable, and

exist.

Natural selection is pretty good at reducing the rate of maladaptive traits over the long term, but a 2021 meta analysis finds 1.7% of the general population has what’s described as a clinically defined high risk of psychosis—meaning that they’ve got symptoms, impairment, and identified risk factors for psychosis.11

This is far higher than rates of other disorders, like achondroplasia or Apert syndrome, with prevelances closer to 0.003% and 0.001%, respectively.12 When we look at disorders like sickle cell aenemia, with rates approaching 1% in places like Uganda,13 we can see there’s a reason for this—being a carrier protects against malaria, which is a big deal in the tropics. In other words, even though sickle cell disease isn’t much good lately, there’s at least some benefit to having one copy if you’re at risk of catching malaria. So, if mental disorders are relatively common, shouldn’t they also have some kind of survival benefit?

It turns out the answer is: not necessarily. The reason? The human brain is inordinately complex. As much as half of the human genome has consequences for neurological development. Every generation introduces new mutations into our genetic blueprint. As errors accrue, insanity results. Or at least, this is the explanation given by a geneticist and a psychologist in their 2006 review, “Resolving the paradox of common, harmful, heritable mental disorders.”14

Speaking as a human being, this is a real tragedy, because it means that mental illness is like a curse of biology that can never be dealt with by selection. No matter how many people are born prone to psychosis, no matter how short, miserable, or unreproductive their lives are, there will always be new insanity-inducing mutations around the corner for the next generation.

Speaking scientifically, though, I love this line of reasoning, because it’s extremely parsimonious and explains all kinds of phenomena. Whether this model is correct or not isn’t even the issue though. Maybe it’s wrong, and we can celebrate or something. But without this idea that mental disorders can keep popping up through random mutation, there was no way to explain how psychosis could be so prevalent without providing some benefit. Now there is a way to explain it, so we aren’t stuck looking for such a benefit using the unconvincing methods of early psychologists.

But What if We Had a Better Methodology?

So forget about everything in the 20th century; forget everything even in the early years of the 21st century. We’ve got much better ways of looking at genetic predisposition to psychosis than checking your relatives, now. And we have better ways of measuring psychosis proneness than Eysenck’s disappointing Psychoticism scale.

These better ways have been a long time in coming, and were probably delayed by the longstanding reluctance the psychological community has shown to moving past the Big Five.15 But Michael Ashton and Kibeom Lee (the psychologists best known for the “big six” HEXACO personality model) have been reporting a seventh personality factor of oddity, schizotypy, psychoticism, or dissociation for over ten years now.16

Moving forward, Serbian researchers have been putting together a scale for psychotic proneness, which they call Disintegration,17 that predicts things like conspiratorial beliefs, intuitive over rational thinking, and refusal to comply with COVID regulations,18 belief in supernatural forces as a rationale for extremist acts,19 a preference for strange rather than conventionally beautiful artwork,20 and alcohol abuse and relationship problems,21 above and beyond the Big Five and HEXACO traits.

The Disintegration scale has its issues—in the last study I just cited, Disintegration shares around 40% of its variance with HEXACO traits, so it’s not measuring psychoticism as cleanly as it could. But that isn’t a problem for the researchers involved, who know that they need to statistically control for the other personality traits when they measure people’s psychosis-proneness via the Disintegration scale.

And this finally brings me to Mina Hagen of the University of Belgrade, whose doctoral dissertation is, in fact, the reason I’m writing this post.

Here’s her abstract:

Examining basic personality traits and creativity, this thesis addresses the question whether a comprehensive personality space comprises five, six or seven factors and explored whether there exists a positive association between creativity and psychoticism or proneness to psychotic-like experiences, as implicated in the mad-genius hypothesis. In two samples (N = 786) the personality factors represented in the HEXACO model, Disintegration (proneness to psychotic-like experiences), PID-5 Psychoticism, creative activities and achievements, and divergent thinking were assessed. Applying Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling, the analyses revealed a clear result: The seven-factor model of the personality space reached best Goodness of Fit indices, with the Disintegration-factor distinct from Openness and other established personality traits. Addressing the mad-genius hypothesis, a test of the location of creativity in the personality space clearly indicates that it was located on the Openness factor. Taken together, these findings clearly refute the quantitative version of the mad-genius hypothesis.22

So if you check that last sentence, you can probably see Eysenck and Tove don’t get a lot of love from the Serbians who are researching all this. Obviously I could have just used this quotation as a big hammer to nail the discussion shut, but you already know I think Tove is 70% right, so I’ll say right away that Mina Hagen’s conclusion is too harsh, and I’ll show you why.

But first of all, take a look at some of the items she used in her Disintegration scale:

General executive impairment": “I frequently repeat useless actions”

Perceptual Distortions: “Sometimes I feel as a split personality”

Paranoia: “I feel being watched”

Depression: “I would like to sleep through this period of my life”

Flattened Affect: “Although I know that some things should upset me, basically I don’t care”

Somatic Dysregulations: “There are times when I can’t hear anything, as if I’m deaf”

Magical Thinking: “I feel the presence of evil forces around me, although I can’t see them.”

Enhanced Awareness: “There are some pieces of music that make me think of images or moving colorful patterns”

Mania: “I am often very excited and happy for no apparent reason”

I love these questions, because they fix everything that disappointed me so much about Eysenck’s Psychoticism scale. And I should have at least some idea of what a good psychometric inventory for crazy ought to look like, since I’ve known my fair share of strange people.

A Nostalgic Interlude: What are Crazy People Like?

When I was a teenager, I had a friend I’ll call D, who was known to be a little strange. He wore homemade armor around, smoked herbs he picked from his backyard, and talked about his plans to travel through an interdimensional portal to visit a world of medieval peasants. To the rest of us he seemed harmless, or even entertaining, and his interest in the fiction I wrote about gargoyles was, to me, positively endearing. Even more: D was the one who first lent me a bootlegged Metallica tape, and I remember staring out the window, lying on the floor, and walking the streets of my hometown listening to that tape for hours.

But D was not always completely harmless. Once, as we sparred in his yard with shortswords he had made, his expression clouded when I touched him with my weapon. Rather than following the casual decorum that usually prevailed among my circle of friends when one person hit the other—that is, rather than granting I’d won the point and breaking off his attacks, D began staring intently at my breast, and his thrusts forced me to defend myself in earnest, depending on the crossguard he’d made to protect me from the point of his weapon. The things he forged were never very sharp, and it’s not likely that I was in any great danger, but it didn’t escape my notice that he was wearing a shirt of mail, while I was totally unarmored, and the two of us were completely alone.

After forcing him back, I stepped away and begged off, insisting that I was done. It was with some hesitation that he relaxed, and accepted his sword back from me. I didn’t see that look in his eyes again for a long time.

The final visit I made to his house—before the ultimate prescription of antipsychotic medication drew a veil across his mind—was in the early evening. His parents greeted me at the door with desperate smiles. This kind of reception was unusual for me, but long-haired and disffected though I may have been, I was one of D’s dwindling links to the outside world. The tidy furnishings of their middle class home made a strong contrast to the gloomy clutter of D’s candlelit room.

The two of us were around 18 at the time, and while he really didn’t watch TV, we talked about girls we knew, and music, and video games, and about the gargoyles perched around his room. He’d recently formed them out of clay. Many of them had unique personalities, and spoke to him on matters he was reluctant to reveal. But as the night wore on, his brows furrowed, his remarks grew more cryptic, and in the shadows of the flickering candlelight his visage took on a Saturnine kinship with the crude figures in his rafters, and it occurred to me that it might be in my best interests to depart. His parents thanked me for coming, and encouraged me to come back soon, but that was the last I saw of D’s gargoyles.

D’s diagnosis at the time was schizotypal. But frankly he’s just one person, and his specific case is much less interesting than the overall picture of Disintegration that resonates with the crazy people I knew from growing up: Strange moods, individualistic attitudes, unconventional dress, suspicion of strangers, supernatural obsessions.

Speaking in terms that are artistically obvious, among my circle of friends I was the most creative person, scribbling lines of poetry, practicing passionately on the piano, or drawing pictures like this:

I’m not saying I was ever much of an artist, but I could at least draw at all. Meanwhile, I knew plenty of crazies who generated nothing creative whatsoever. Whether they were lying around in a funk, harrassing people with baseless accusations, or screaming unintelligably, many of them just annoyed everybody who knew them.

But you can probably see why I think the hobbies that D pursued definitely had a flavor of creativity about them—at least, before his condition deteriorated to the point that he received a diagnosis and medication. So, did the edge of madness drive his creativity? Or did his madness merely redirect and stunt a creativity arising from somewhere else?

To answer this question, I’m going back to Mina Hagen’s dissertation.

Creativity Does Not Relate to Disintegration

In her dissertation, Mina Hagen surveyed 786 students and community members. She was able to clearly recover seven distinct personality traits under factor analysis, with the first factor being Disintegration (probably due to the large amount of psychosis-related content). She also included several creativity scales, and, “the extension analysis provides striking evidence to the fact that creativity is located on the openness factor in the personality space, and not on the factor representing proneness to psychotic-like experiences. These results are obviously incompatible with the mad-genius hypothesis.”23

You can see she’s very keen to do away with the idea that creativity has anything to do with psychosis, but here are her results:

All of her creativity measures clearly load positively on Openness (boxed in red), exactly where we would expect; Openness is a trait broadly related to imagination, curiosity, aesthetic sensitivity, and creativity. And the loadings on Disintegration (in green) are extremely small, and essentially zero.

But this doesn’t mean creativity is unrelated to psychosis-proneness. It means that creativity must be related to psychosis-proneness.

How Can a Zero Correlation Imply an Actual Relationship?

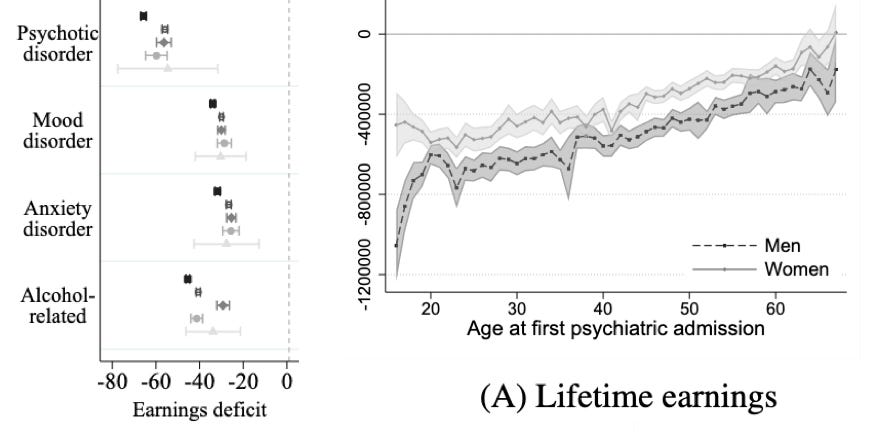

Mental illness is debilitating. This is something I hope most of my readers understand without much trouble, but the argument I’m going to make will hinge on this point, so I want to emphasize that having a diagnosis is associated with decrements to lifetime earnings, with psychotic disorders of the kind we’re discussing here having the most severe impact on economic outcomes. Since early age of onset is an indicator of greater individual susceptibility to psychosis,24 it looks like greater susceptibility to psychosis is also associated with greater lifetime deficits in economic achievement, according to the charts below, which I grabbed from a 2021 paper:25

The graph at right shows a clear relationship between mental health and lifetime earnings: The earlier a person was admitted for psychiatric evaluation, the worse their lifetime earnings. Earnings are a reflection of many things, but they include creative work. It should be obvious that if psychosis-proneness negatively impacts earnings, it’s going to negatively impact things like creativity, too. But if that is the case, then why does Mina Hagen not find a negative relationship between Disintegration and creativity?

What we expect to see, by any ordinary reasoning, is a table like this:

We’re talking about people with increasing levels of depersonalization, derealization, dissociative identity disorder, schizotypy, schizoid disorders, and schizoaffective disorders, here. That’s the very obvious meaning of Disintegration. If, after surveying hundreds of people and carrying out the analysis you don’t find the above results staring back at you from your computer screen, and instead find near-zero (or even positive!) relationships between Disintegration and creativity, well, why might that be? Is it because the relationship looks like this?

Even if it doesn’t look like this, and it’s truly just a flat relationship, no curve at all, well, that still would be very surprising, wouldn’t it? “Crazy people actually not so bad at being creative (but still suck at everything else)” is an interesting headline to me.

So while Hagen’s dissertation is enormous, and while I’m glossing over a lot of the detail, the conclusion from modern psychological research supports the idea that, while eccentricity may mostly cause problems, the loss of creativity isn’t one of them—or at least, not until you’re ready for the straight jacket, the friendly nurses, and the colorful pills.

What About Newer Genetic Studies?

Same conclusion, but with far better studies. Rather than looking at people’s relatives, we can look at their DNA through polygenic scores, finding genes for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are related to membership in creative professions.

We tested whether polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder would predict creativity. Higher scores were associated with artistic society membership or creative profession in both Icelandic (P = 5.2 × 10^6 and 3.8 × 10^'6 for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder scores, respectively) and replication cohorts (P = 0.0021 and 0.00086). This could not be accounted for by increased relatedness between creative individuals and those with psychoses, indicating that creativity and psychosis share genetic roots.26

Another study found genes related to schizophrenia and language performance perdicted membership in creative professions:

[G]enetic variants relating to increased risk for schizophrenia and better language performance are overrepresented in individuals involved in creative professions (n = 2953) compared to the general population (n = 164,622).27

Genes related to depression and risk-taking are also related to creativity:

Two cohorts of Han Chinese subjects (4,834 individuals in total) aged 18–45 were recruited for creativity measurement using typical performance test… PRS analyses demonstrated significantly positive genetic overlap, respectively, between creativity with schizophrenia… depression… general risk tolerance… and risky behaviors… Genetic variations that predispose to psychiatric disorders and risky behaviors may underlie part of the genetic basis of creativity, confirming the epidemiological associations between creativity and these traits.28

In conclusion, this is exactly what Eysenck had been writing about 30 years ago. It may not be exactly what Tove was talking about—she was talking about autism, or a certain lack of social ability, or whatever, relating to genius. But psychosis predicting artistic creativity is pretty close to what she was talking about, so she’s clearly more right than wrong, and I was clearly more wrong than right to argue with her about it.

And if I have to give a number for how correct she was? OK, no problem, I’ve got you covered, right here, 70%:

Reddy, I. R., Ukrani, J., Indla, V., & Ukrani, V. (2018). Creativity and psychopathology: Two sides of the same coin?. Indian journal of psychiatry, 60(2), 168-174.

Reddy, I. R., Ukrani, J., Indla, V., & Ukrani, V. (2018). Creativity and psychopathology: Two sides of the same coin?. Indian journal of psychiatry, 60(2), 168-174.

Motto A. L., Clark J. R. (1992). The paradox of genius and madness: Seneca and his influence. Cuadernos de Filologı´a Cla´ sica. Estudios Latinos 1992; 2: 189–200.

Eysenck, H. J. (1995). Genius: The natural history of creativity. Cambridge UniversityPress.

Eysenck, H. J. (1993). Creativity and Personality: Suggestions for a Theory. Psychological Inquiry, 4(3), 147–178. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0403_1

Heath, A. C., & Martin, N. G. (1990). Psychoticism as a dimension of personality: a multivariate genetic test of Eysenck and Eysenck's psychoticism construct. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(1), 111.

Knežević, G., Lazarević, L. B., Purić, D., Bosnjak, M., Teovanović, P., Petrović, B., & Opačić, G. (2019). Does Eysenck's personality model capture psychosis-proneness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 143, 155-164.

Eysenck, H. J. (1983). The roots of creativity: Cognitive ability or personality trait? Roeper Review, 5,10-12.

Kyaga, S., Lichtenstein, P., Boman, M., Hultman, C., Långström, N., & Landen, M. (2011). Creativity and mental disorder: family study of 300 000 people with severe mental disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(5), 373-379.

Parnas, J., Sandsten, K. E., Vestergaard, C. H., & Nordgaard, J. (2019). Mental illness among relatives of successful academics: implications for psychopathology‐creativity research. World Psychiatry, 18(3), 362.

Salazar de Pablo, G., Woods, S. W., Drymonitou, G., de Diego, H., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2021). Prevalence of individuals at clinical high-risk of psychosis in the general population and clinical samples: systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain sciences, 11(11), 1544.

Keller, M. C., & Miller, G. (2006). Resolving the paradox of common, harmful, heritable mental disorders: which evolutionary genetic models work best?. Behavioral and brain sciences, 29(4), 385-404.

Ndeezi, G., Kiyaga, C., Hernandez, A. G., Munube, D., Howard, T. A., Ssewanyana, I., ... & Aceng, J. R. (2016). Burden of sickle cell trait and disease in the Uganda Sickle Surveillance Study (US3): a cross-sectional study. The Lancet Global Health, 4(3), e195-e200.

Keller, M. C., & Miller, G. (2006). Resolving the paradox of common, harmful, heritable mental disorders: which evolutionary genetic models work best?. Behavioral and brain sciences, 29(4), 385-404.

Readers who know me well may be surprised to know I experienced this reluctance to move past the Big Five myself when I first discovered the HEXACO. Though it really only lasted about five minutes, it could be summed up in my thoughts “But I spent all this time perfecting a quick Five Factor inventory,” and secondly “No, wait, they found a second Agreeableness? That’s wrong, the next factor should be a second Openness to Experience.” Disintegration was the factor I had been anticipating.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2012). Oddity, Schizotypy/dissociation, and personality. Journal of Personality, 80(1), 113-134.

Knežević, G., Lazarević, L. B., Bosnjak, M., & Keller, J. (2022). Proneness to psychotic‐like experiences as a basic personality trait complementing the HEXACO model—A preregistered cross‐national study. Personality and Mental Health, 16(3), 244-262.

Stanković, S., Lazarević, L. B., & Knežević, G. (2022). The role of personality, conspiracy mentality, REBT irrational beliefs, and adult attachment in COVID-19 related health behaviors. Studia Psychologica, 64(1), 26-44.

Međedović, J., & Knežević, G. (2019). Dark and peculiar: The key features of militant extremist thinking pattern? Journal of Individual Differences, 40(2), 92–103.

Stojilović, I. Z. (2023). The Effects of Psychotic Tendencies on Aesthetic Preferences of Paintings. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 41(2), 372-391.

Nedeljković, B., & Topalović, N. (2023). Disintegration predicts problem alcohol and drug use, quality of life, and experience in close relationships over the Big Five and HEXACO personality traits. Primenjena psihologija, 16(2), 269-294.

Hagen, M. M. (2023). Moving towards a comprehensive unified trait structure: clarifying the placement of openness, disintegration and creativity in the personality space. Универзитет у Београду.

Hagen, M. M. (2023). Moving towards a comprehensive unified trait structure: clarifying the placement of openness, disintegration and creativity in the personality space. Универзитет у Београду.

Köhler, S., van Os, J., de Graaf, R., Vollebergh, W., Verhey, F., & Krabbendam, L. (2007). Psychosis risk as a function of age at onset: a comparison between early-and late-onset psychosis in a general population sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42, 288-294.

Salokangas, H. (2021). Mental disorders and lifetime earnings. IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEc.

Power, R. A., Steinberg, S., Bjornsdottir, G., Rietveld, C. A., Abdellaoui, A., Nivard, M. M., ... & Stefansson, K. (2015). Polygenic risk scores for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder predict creativity. Nature neuroscience, 18(7), 953-955.

Rajagopal, V. M., Ganna, A., Coleman, J. R., Allegrini, A., Voloudakis, G., Grove, J., ... & Demontis, D. (2023). Genome-wide association study of school grades identifies genetic overlap between language ability, psychopathology and creativity. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 429.

Li, H., Zhang, C., Cai, X., Wang, L., Luo, F., Ma, Y., ... & Xiao, X. (2020). Genome-wide association study of creativity reveals genetic overlap with psychiatric disorders, risk tolerance, and risky behaviors. Schizophrenia bulletin, 46(5), 1317-1326.

Synchronicity on 'disintegration' but not quite a 'snap'.

https://substack.com/home/post/p-93317748

Images of Ego Death

I'll note that I do not think disintegration and ego death (via meditation or psychodelics) are the same.

However.... 'disintegration' affects 'worlding' as well 'selfing'.

Dark matter is one of the worst misnomers in scientific history. It’s the word we ascribe to the cause of strange phenomena at the truly macro scale we can’t explain with current physics and matter concentrations alone.

It doesn’t mean it’s actually matter.

When someone says; “Uhhhh, actually here’s a theory that says dark matter isn’t actually matter but a tweak of physics.” they are misunderstanding the problem. No scientist is actually claiming dark matter has to be matter, just that it there is a problem with the density and rotation of galaxies that could be explained by a large amount of invisible matter.