There are words for emotions foreign languages have that don’t exist in English. One is Tarab, a mystical feeling of ecstacy induced by music. Another is dadirri, a sense of mindful, meditative listening. But you’ve more likely heard of Scadenfreude, the sadistic satisfaction derived from the suffering of another.

Are these emotions unknown to English speakers? Do these emotional states transcend the comprehension of those locked within a narrow culturalal space? Or can they be understood in terms of shared emotions we all understand?

I can’t be too confident about Tarab or dadirri, but I can tell you exactly what Schadenfreude feels like.

At the time this post was written, Biden dropped out of the 2024 race, leaving Kamala Harris as the frontrunner against Trump. Speaking dispassionately, I would rather see Harris attain the presedency, as she would more likely burn through American power for the sake of environmental controls and cooperation with foreign governments; my preference would be to let an already dying empire continue to fade while staunching environmental damage and preserving stability in the international community. But speaking emotionally, even today I still remember the tears, the wailing, the abject hysteria from the coddled and comfortable classes in the face of Clinton’s 2016 defeat. And while I’m big enough to realize this probably isn’t something I should push for, I’m still human enough to enjoy it when those who have oppressed me for so long as I can remember are seen to publicly and performatively suffer.

And I can still describe the feeling from eight years ago: Schadenfreude is like walking the streets on a long, hot, wearying day, and then getting a sip from an iced mocha. There’s a sweetness to the experience, a satifying feeling of cold, laced with dark aromas and an underlying bitterness and that gives Schadenfreude a complexity much richer than something more straightforwardly sweet, like joy, triumph, or love.

Schadenfreude is not a uniquely German experience. But is schadenfreude a distinct experience? Do we need a word for it? Or can it simply be seen as a blend of more basic emotions, an experience at the crossroads of satisfaction and spite?

Basic Emotions

Early research suggested that there are six basic emotions: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, disgust, and surprise.1

There were regarded as part of a typology—happiness is a distinct type of emotion from sadness; disgust is a distinct type of emotion from surprise. An obvious question then is why, for example, fear and disgust seem so similar. This similarily is both in terms of our experience of the emotions as galvanizing, negative states which stimulate us to withdraw from or avoid whatever we’re looking at, and also in terms of the way the emotions appear to others. As an example, consider this woman’s body language:

She doesn’t look happy, surprised, or angry to me. But if disgust and fear are basic, discrete emotions, shouldn’t we be able to tell which one she’s feeling right now? I find it difficult to decide whether she’s experiencing fear or disgust without knowing whether the stimulus to which she’s responding is a loaded gun pointed at her face, or an ad for a modern movie. She just doesn’t like whatever’s going on.

Stupid Ideas About Feeling

This kind of categorical approach to emotions that treats them as discrete types may be useful, but on some level it reminds me of the way I started out trying to make sense of emotions in my early teens. I had no way of organizing the shimmering sensations that colored my existence, so I relied on the framework provided by traditional Christianity. What I decided was that feelings could be broken into four basic categories, as shown in this helpful infographic:

Looking at this years later, all I can say is I find it reassuring to see grown men with psychology degrees like Dr. Henriques still using this kind of reasoning as they reassure you that it’s all about having a body, a heart, a mind, and a spirit, and that if you move to the top of your skull, you will find that “this is where your spiritual orientation lies.”2 (Some of us may be a little pointy-headed, IDK.)

And I don’t know why Dr. Henriques is claiming this, but in my case it probably helped a great deal that, while I had grown up with rabbits and cats, I’d never owned a dog. It’s pretty well assumed by Christians that animals have no spirit and can never experience eternal life in heaven,3 but simple observation of dogs would have told me immediately that dogs can definitely experience love, along with the moral intuitions I attributed to the human spirit.

But if dogs can be driven by feelings of love or hate or right or wrong, and dogs don’t have spirits, maybe those deeper feelings should somehow be located elsewhere? Yet doing that would leave the spiritual quadrant of my little chart looking pretty vacuous. What does the spirit really do except prompt feelings of love or virtue? And more importantly, if moral intuitions are part of the biology we share with animals, how can a spirit which lives on after death be responsible for our sins, or seeking forgiveness from them? Maybe virtue lies in the heart, which is a decidedly Egyptian notion. And after all, God hardened Pharaoh’s heart and drove him to sin against His chosen people; wouldn’t this mean God made Pharaoh sin? “God judges the heart;” so does Pharaoh go to Hell because God made him cruel?

Fortunately I didn’t have a dog, so I didn’t have to wrangle with those problems. But I did have a lot of curiosity about this model, and I could already ask: Where did humor fit in? It seemed like a mental phenomenon somehow, but animals didn’t seem to laugh; was humour spiritual? It obviously had an emotional component, so maybe humour was a blend of feelings in the heart and the mind?

So thinking more about it, I tried instead to figure out about emotions without classifying them as part of these four layers.

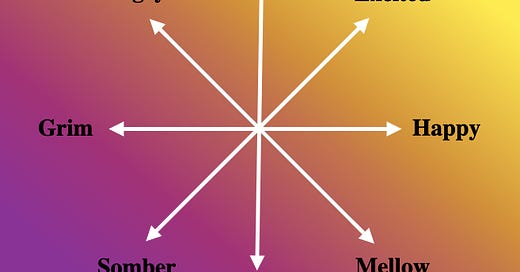

And what I came up with was something much more interesting:

Two Dimensions of Emotion

A lot of this came from music. I associated the emotions on the right with music in a major key, and thought of them as being “lighter” than emotions on the left, which were “more serious,” and associated with music in a minor key. The emotions higher up were “energized” and down below were “relaxed.”

And those of you who are familiar with humorism might at this point notice that I’d basically just invented humorism:

The four humors have complicated ties to medicine and elementalism; they can be traced all the way back to Hippocrates. The phlegmatic temperament is described as peaceful and calm, melancholy as sober and pessimistic, choleric as touchy and impulsive, and sanguine as lively and easy-going.4 But I wasn’t thinking about layers of blood or ways of treating diseases or coming up with an ideal diet; I was just thinking about feeling.

What’s more interesting is the way my thinking about feeling relates to things psychologists had secretly been researching without telling me without my having had access to the Internet, which was essentially this:

This is a graphic sumarizing the results from numerous individual studies.5 They use a lot of the same terms I used: alert, excited, and happy all match, while the feelings I called mellow and restful are a good match for the terms in the lower right and bottom ranging through serene, relaxed, calm, and fatigued.

The problem I have with these results is that they describe the left side of the emotional map in a… weird way. Instead of feelings like anger showing up in the high-energy negative side, we have terms like nervous, tense, or stressed. Neither of the words upset or sad capture feelings I would describe as grim. And the low-energy side has lethargic and depressed which feel closer to boredom than they do to seriousness or somberness.

On the one hand, we could just say I described the negative emotions incorrectly. Right? I was an ignorant teenager trying to figure things out before he even had a computer in his room. But on the other hand, I didn’t make any of those words up. So where do they fit on the map? Are boredom and grief the same kind of thing? Are grimness and upset the same kind of thing? Are anger and nervousness the same kind of thing? And where in the world is Schadenfreude supposed to fit?

Well, here’s an individual study with many more terms.6 This result may take a bit to get used to—it would need to be flipped and then rotated slightly to match the diagram above. (When you’re familiar with factor analysis, you get used to seeing solutions that need to be flipped or rotated to be recognizable). Here we see I wasn’t exactly making up emotions, but gloomy and bored are very near one another, and while anger isn’t there, we do have annoyed very close to fearful:

This is just one result, and maybe it’s just a little weird. But if so, this study gives a result that’s even clearer:7

Or if you don’t like that one, here’s the emotional map from a study that included subjects from Estonia and Greece:8

Again and again we see sad and bored very near one another, while afraid and angry are right next to one another. Are sadness and boredom really similar emotions? Are afraid and angry just synonyms?

If you have any interpersonal skills whatsoever, you’ll know sadness and boredom are pretty different, and should spur different responses; you can’t really console a bored person, or tickle a sad person happy. It’s even worse for fear and anger, which really feel markedly different. Forget how strikingly different it feels to be angry or afraid—forget the icy hand of panic in your chest, or the blaze of anger that sears your vision red and clenches your fingers into fists. Forget being a human that actually has emotions of your own to experience and remember; fear and anger are so different you can even discriminate between them in other people with the merest glance. Heck, let me make it even harder and show you cats rather than people; do you really have trouble telling which cat is scared and which is mad?

Anger is an interesting emotion when you think about it. Most aversive stimuli encourage us to leave. We respond to tasteless jokes, arrogant posturing, and Walt Bismarck’s latest Substack by going someplace else. But as psychologists point out, anger is strange; it actually makes us want to approach the stimulus that makes us angry.9

This is probably why I’ve killed somewhere around a thousand black widows: Back when I lived in the American southwest, finding stiff, disorganized webbing in the yard my children played in made me angry, so with the setting of the sun I took a flashlight in one hand, grabbed a stick in the other, and became Apple Pie, Bane of Latrodectus.

This is also why people keep arguing on the Internet; they’re always mad at each other, and the more they see of each other the more angry they get, but they can never kill one another online, so unless they stop to think they should leave, they just get stuck in an endless hate loop.

But this still leaves us with a question: How do we fit anger, fear, boredom, and sadness onto a two-dimensional map of emotion in a satisfying and plausible way?

And The Answer Is

Oh, easy. You just make the map three-dimensional.10

Pleasant and unpleasant emotions still map to the right and left, with high and low energy states at the top and bottom. But because your computer screen is 2D, this map includes what researchers refer to as “dominance” and “submissiveness” using green and purple. Although I only picked one term for each corner of the map, the upper right green area includes other states like domineering, self-satisfied, and triumphant which, alongside aggressive, do at least seem like cousins of Schadenfreude. That is, the kind of joyful-but-also-mean feeling seems reasonably well captured by this map, with the only feature of Schadenfreude that makes it unique being the way it’s triggered by crushing your enemies, seeing them driven before you, and crucially, hearing the lamentations of their women.

The terms dominance and submissiveness aren’t necessarily that well chosen. They do reasonably capture the distinction between fear and anger, where a dominant position would reasonably be expected to make a person (or a cat, or whatever) react angrily to challenges rather than running away.

But the terms strike me as rather gendered, and while dominance may seem very male and submissiveness may seem very female, sex differences are actually minor; the stereotypical female is only slightly more prone to emotions at the bottom and purple edge of the map, while males are more prone to emotions at the top green edge.11 So don’t worry guys, if you do ever find yourself experiencing a purple emotion, it’s OK (and besides I won’t tell anyone). And I’ll also clarify that aroused doesn’t exactly mean what you probably think it means, because the term sexually excited is also found in the upper right quadrant, and isn’t dominant or submissive.

So unfortunately as soon as we get a three-dimensional model to deal with the split between fear and anger, we’re stuck admitting that three dimensions still doesn’t capture the amount of variation that actually exists in emotion, because it’s easily possible to be overwhelmed with joy but not sexually excited, in just the same way that it’s possible to be sad but not bored.

But just in case you think maybe four dimensions is enough, sorry, it isn’t enough, because there are also plenty of other terms in these studies like nauseated (negative-submissive), arrogant (energetic-dominant), and affectionate (positive-energetic-dominant) that already don’t fit, and by now you probably realize the real lesson, which is:

Science is extremely good at opening doors.

Behind every door, another door awaits.

Ekman, P. (1992). Are there basic emotions?. Psychological Review, 99(3).

Henriques, G (2021, September 3). The Four Vertical Layers of the Human Psyche. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/theory-knowledge/202109/the-four-vertical-layers-the-human-psyche

Dy, G. (2024, March 5). What is the difference between a soul and a spirit? Christianity.com. https://www.christianity.com/wiki/salvation/difference-between-a-soul-and-a-spirit.html

Stelmack, R. M., & Stalikas, A. (1991). Galen and the humour theory of temperament. Personality and Individual Differences, 12(3), 255-263.

Barrett, L. F., & Russell, J. A. (1999). The structure of current affect: Controversies and emerging consensus. Current directions in psychological science, 8(1), 10-14.

Adapted from Rusting, C. L., & Larsen, R. J. (1995). Moods as sources of stimulation: Relationships between personality and desired mood states. Personality and individual differences, 18(3), 321-329.

Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of personality and social psychology, 39(6), 1161.

Russell, J. A., Lewicka, M., & Niit, T. (1989). A cross-cultural study of a circumplex model of affect. Journal of personality and social psychology, 57(5), 848.

Carver, C. S., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2009). Anger is an approach-related affect: evidence and implications. Psychological bulletin, 135(2), 183.

Russell, J. A., & Mehrabian, A. (1977). Evidence for a three-factor theory of emotions. Journal of research in Personality, 11(3), 273-294.

Mehrabian, A., & O'Reilly, E. (1980). Analysis of personality measures in terms of basic dimensions of temperament. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 492-503.

In my opinion, How Emotions are Made by Lisa Feldman Barrett is a very interesting book on this subject. I think the book is badly written because it repeats over and over again that detailed emotions are not innate (obviously many people actually believe they are), but it also summarizes some interesting research that underbuilds that opinion.

After reading that book, I think about emotions as social explanations for states of mind. I mean, if a person says "I'm feeling disappointed", that really means "I'm in a sullen mood and my explanation is that I didn't get what I expected". The same with schadenfreude: "I'm feeling elated and my explanation is that an opponent faces hardship".

It is all a lot about social predictability. There are social conventions dictating when a certain feeling is appropriate. Words for feelings are one part of those conventions. We use those words in order to communicate that our emotions are orderly and predictable.

been thinking more generally about this, what comes to mind with the German word is the measure for 'punitive' like schadenfreude is vicarious punishment, maybe with a empathic dimension with nurturing at one end and punitive on the other, until the pain inflicted no longer cares about what the receiver feels, deserved or underserved.. and it is off the scale. A lot of shoulding the world into place seems to be about how we police this, both in doing it and in stifling it.